Each painting of hers tells a story. In one, tribespeople are clearing a parcel of land in the forest to farm on it and grow food. In another, they are depicted as singing and dancing in front of three branches of the Karma tree in connection with a harvest festival. “The festival is held on Ekadashi in the month of ‘Bhado’ and takes it name from the Karma tree. After pujas and a full night of song and dance, the Karma branches are taken to all the houses in the village where offerings are made to it. The branches are later immersed in water,” says Oraon artist Anamika Bhagat.

Anamika who is in the State capital for a two-day seminar ‘Glimpses of tribal life: Knowledge and intangible expressions’ organised by the Loyola College of Social Sciences in collaboration with KIRTADS, Kozhikode, explains that their art, also called Oraon, has been handed down from generation to generation.

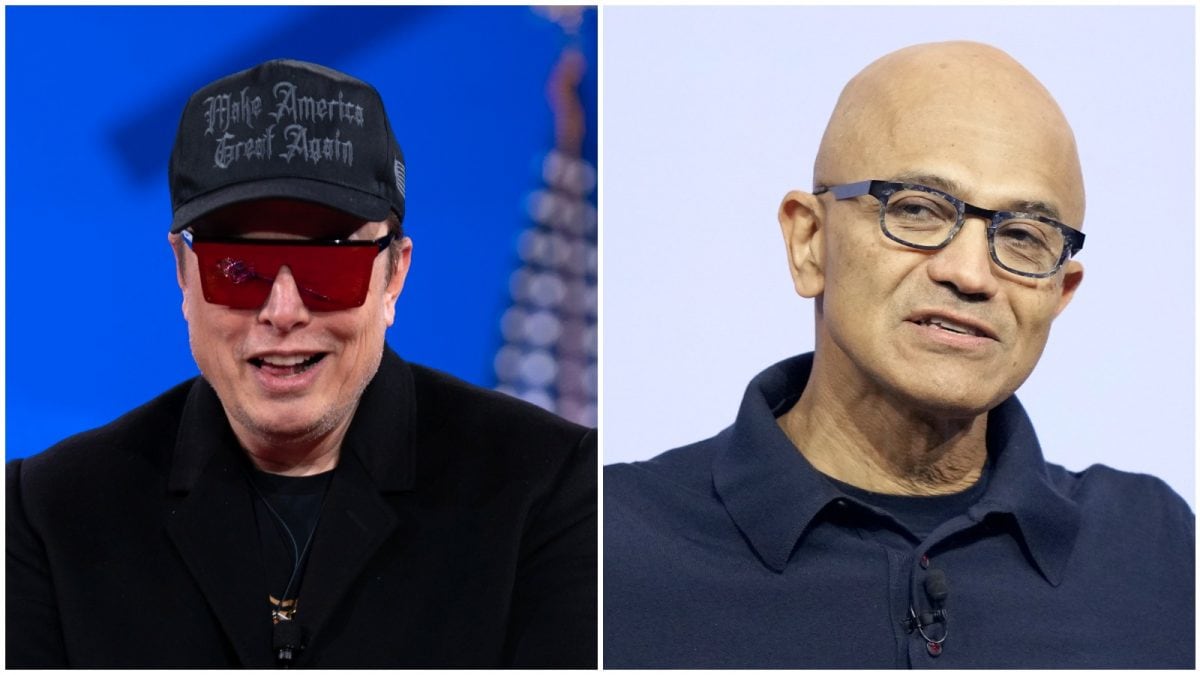

Paintings by Oraon artist Anamika Bhagat from Chhattisgarh displayed during a national seminar on Tribal life held at Loyola College of Social Sciences in Thiruvananthapuram on Thursday. | Photo Credit: NIRMAL HARINDRAN

Traditionally, when the Oraon cleaned their houses and got them ready for festivals, they used their fingers to draw arch-shaped patterns called Oraon banna on the walls. These patterns were drawn from right to left using black mud.

“Gradually, we started incorporating our everyday life, festivals, traditions, clothing, farming, and nature on not just walls but canvas, sheet, and other media too,” says Anamika who began Oraon art only a decade ago.

Long process

Different kinds of soil are used for Oraon art. However, black soil is not easily available; one has to go to the forests in our village and dig to find it. “Other than black soil, we use green leaves and other natural substances. We can use acrylic colours if asked to, but that is not what we usually use in our works,” she says.

The soil has to be soaked in water for days to make it soft and malleable. Different soils may contain sand in varying proportions and so both have to be separated. Then, glue is added to the soil. On canvas, the background has to dry completely before continuing with the rest of the painting.

Keeping the art alive

Anamika who hails from Shaila village in Jashpur district of Chhattisgarh but lives in Bhopal, Madhya Pradesh, says there are very few Oraon artists in their community. Anamika and her elder sister Sumanti Devi are the only ones from their village who are actively involved in keeping Oraon alive. “Some other members of our family also make Oraon paintings, but visits to exhibitions, talks, and other events are mostly done by us.”

Migration for education and employment also pose a hurdle. When the younger generation is hardly home, how will they know the importance of keeping our cultural traditions alive, she asks.

“We hope that our family members take Oraon art forward. We also want to teach anyone interested in learning Oraon, so that the next generation knows about our culture.”

“I will continue making Oraon art till the moment I can,” says Anamika who has participated in a number of exhibitions and events to popularise Oraon art.

.png)

.png)

.png)

1 week ago

7

1 week ago

7

English (US) ·

English (US) ·