Every day, before the first rays of dawn stretch across the horizon, 54-year-old Sidharthan sets off on a quiet voyage across Vembanad Lake.

From a narrow river mouth in Vechoor, a serene village cradled in the backwaters of Kottayam, he paddles out in his modest canoe. Here, the countless waterbodies converge into the brackish vastness of Kerala’s largest lake.

Tools of the trade

Equipped with a few metal baskets and a mesh shovel with an adjustable handle, Sidharthan rows steadily past the Thanneermukkom Bund, a man-made barrier that divides the lake into two distinct halves: one holding back brackish water and the other fed by freshwater rivers.

On most days, he rows nearly five kilometres into the lake’s sweeping expanse, scanning the surface for subtle signs of depression on the lakebed. When he spots one, he lowers the shovel and begins sifting through the muddy bottom. For hours, he hoists up basket after basket of small black clams, filling his boat.

Sidharthan turned to the lake as a teenager to support his family. Back then, it was just a clam rake and strong lungs. He would dive into the shallows, groping through the silt and collecting clams with bare hands, holding his breath for minutes underwater. Today, the hand-operated shovel spares him the dives, making the work less punishing and far more efficient. “I’ve been doing this for nearly thirty years, come rain or shine, winter or summer,” he says, guiding his canoe back to shore as the morning sun begins to beat down.

“But you don’t see the abundance we once did,” he rues. It’s just another summer morning on Vembanad, but the shoreline he nears is already baking like an oven.

Something is cooking here

Behind a thick fringe of trees and tangled undergrowth, the riverbank has transformed into a roaring outdoor kitchen. Smoke billows from firewood hearths. Flames dance under massive iron pots balanced on stone stoves as women prepare to boil the morning’s catch.

The mounds of empty clam shells that lay scattered across the banks tell the visitors that the clam fishery has been a way of life here for ages.

As Sidharthan’s canoe touches the muddy shore, his wife Kumari emerges from behind a stove. Together, they begin unloading the fresh catch.

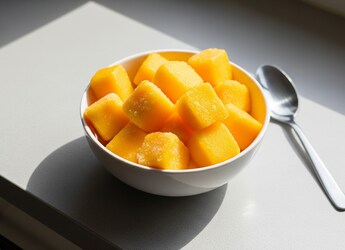

The juicy final product

Kumari then lifts a heavy basket of clams onto her head with ease, heading straight for the boiling pots. The clams are simmered for hours; once the shells are discarded, what remains is a delicacy cherished across Kerala, tender, juicy clam meat.

Women boil freshly caught clams over wood-fired hearths along a riverbank, preparing them for meat extraction. A scene from Vechoor near Vaikom. | Photo Credit: VISHNU PRATHAP

Women sell the clam meat at the nearby Ambika Market Road. The meat, which is in high demand, is usually sold out within a few hours, says Vinoop Chellappan, secretary of the Vechoor Lime Shell Cooperative Society.

Each clam harvester earns around ₹1,500 a day. Also, the clam farmers’ cooperative earns substantial revenue from selling discarded lime shells, which fetch around ₹4,000 a tonne. The shells are powdered and processed to be used in poultry feed, explains Vinoop.

A worker puts clams into a vessel of boiling water. | Photo Credit: VISHNU PRATHAP

Yet, life is far from easy for these harvesters. The black clam population in the lake has seen a marked decline in recent years, jeopardising both livelihoods and a centuries-old tradition. Mani Lal, a 54-year-old veteran from Vechoor, voices his concern. “Earlier, clams could be collected from anywhere in the lake. Now, the situation is different,” he laments.

The illegal force steps in

As night falls, clandestine collectors quietly slip into the shallows, scouring the lakebed for hours and loading their boats with juvenile black clams. They sell both clam meat and shells at lower prices and without paying royalties, thus upsetting the ecology and economy of the region.

“The harvesting of mallikalla, juveniles under the size of 20 millimetres, goes unchecked in many parts of the lake,” says Vinoop.

The problem is acute, especially in areas north of the Thanneermukkom bund, where salinity levels are higher. “That area has become a hotspot for unauthorised harvesting,” confirms a senior Fisheries department official.

The department has stepped up night patrolling in the region. Plans are afoot to increase the surveillance with support of local fishing communities, says the official, who wished not to be quoted.

Juveniles do the trick

The clam production from the lake, which plummeted to 39,243 tonnes in 2020 from the 75,592 tonnes in 2006, witnessed a seven-fold increase in 2022 following the release of 140 tonnes of juveniles in 2020.

Two years later, the production was 52,582 tonnes, which later dropped to 45,000 in 2024, says R. Vidya, Senior Scientist, Shellfish Fisheries Division of the Central Marine Fisheries Research Institute, Kochi.

Black clams grow best in 70-80% sandy lakebeds and can handle shifts in salinity, though such changes may disrupt breeding cycles. An estimated 6,000 people in the Vembanad basin depend directly on clam harvesting. The sector contributes roughly 70% of the region’s fishery wealth. The illegal harvesting is a matter of concern, says Vidya.

A clam collector emerges from the lakebed with freshly gathered black clams. | Photo Credit: VISHNU PRATHAP

Anthropogenic activities too are putting pressure on the fragile lake system and the clam fishery. Nandini Menon, Principal Scientist at the Nansen Environmental Research Centre India, Kochi, points out that human activities are severely impacting the fishery wealth of the backwater ecosystem.

When oxygen is sucked out

“Take E. coli contamination, for example,” she points out. “The levels are alarmingly high, around 30,000 cells per millilitre, compared to the permissible limit of just 5 cells per millilitre. This influx of nutrients, often from the disposal of partially or untreated waste into the lake system, fuels algal blooms. That, in turn, creates a highly toxic environment by depleting oxygen levels in the water and degrading the natural habitat for clams,” she points out.

The heavy siltation of the lakebed is also taking its toll on the ecosystem. “Clams are filter feeders. The excessive sedimentation disrupts the normal physiological functions of the animals and hinders their growth,” she explains.

“To make things worse, the average temperature and salinity levels of the lake have been rising, compounding the stress on clam populations,” says Nandini.

Meanwhile, the shores of Vembanad are being increasingly lined with rising mounds of discarded clam shells layered thick. These ghostly heaps, visible all around the lake basin, signal yet another deepening crisis. The demand for the shells has dropped since the pandemic.

The Karappuram Lime Shell Vyavasaya Cooperative Society in Muhamma, Alappuzha, established in 1961, was once a bustling hub. At its peak, it operated seven depots and supported over 1,000 members harvesting the shells. Today, just one depot remains and membership has dropped below 100.

Over a year ago, the society abandoned white shells altogether, switching to live-harvested black shells in a bid to survive. Though some recovery followed, the future remains uncertain. Piles of unsold black shells at the Charamangalam depot tell a tale of ongoing hardship.

“We switched to live-harvested black shells just to stay afloat. Things have improved a bit. Yet, we are not out of the woods,” says P. B. Sasidharan, a director of the society.

Once prized for cement, paper, poultry feed, and soil treatment, lime shells have been edged out by cheaper substitutes such as dolomite and limestone. This shift has gutted demand. The cooperative network, once a major employer in the backwater landscape, is now yearning for urgent government support.

Of the 13 lime shell cooperatives in Kerala, 11 work with black clams, while two still focus on white shells. The white shell societies, supplying to cement and paper industries, are on the verge of collapse. Even the black shell sector is faltering, say those in the industry.

“Tamil Nadu was once our biggest market, but after dolomite arrived, they stopped buying from us. The government must intervene, especially in promoting lime shell use in agriculture. We’ve raised the issue with the government,” says K.S. Damodaran an office bearer of the Kakka Vyavasaya Sahakarana Sangham (CITU).

T. D. Jojo, the project coordinator of Ashoka Trust for Research in Ecology and Environment, an NGO, working in the region, too underscores the urgency of finding alternative markets and value addition for clam shell and meat. “Collectors risk their lives daily for this work and aren’t getting their due,” he says. “They’re facing both a fall in clam stocks and in demand,” he feels.

“The clam population is showing some signs of recovery, thanks to the efforts of the State Fisheries department and other agencies. However, the marketing challenges of clamshells need to be addressed.” he suggests.

Like the clam harvesters Sidharthan and Lakshmi, the lime shell industry, which provided a livelihood option to hundreds of workers of the region, and the lake and its fragile ecosystem are struggling to survive. It’s not just a species that is on the brink of a crisis, but the waterscape itself is yearning for help.

Published - June 05, 2025 11:37 pm IST

.png)

.png)

.png)

1 day ago

5

1 day ago

5

English (US) ·

English (US) ·