ARTICLE AD BOX

This one’s especially for them, the ones who wear ‘fearless’ t-shirts a tad bit too proudly!Human beings, as it turns out, aren’t entirely fearless. However, they are rather minimalist when it comes to innate fears.

These aren’t gamma‑ray phobias or existential dread—they’re simpler, more down‑to‑earth.

Believe it or not, we’re born wired with just two primal fears—and those are the fear of falling and the fear of loud noises. Everything else? Learned through our interactions with the world. Intrigued?Let’s take a quick ride through your first two fears and explore why the rest are mostly social souvenirs.

The fear of falling (the ‘visual cliff awakening)

Picture this: you’re six months old, crawling on a platform.

Ahead of you—plummeting to the floor below—is nothing but clear plexiglass. A trusted figure is calling, “Come on, sweetie!” But you hesitate. Most infants don’t cross that transparent glass. Turns out, we detect the drop and recoil instinctively. That hesitation isn’t learned—it’s built-in. This experiment, known as the ‘visual cliff’ (1960) – where infants aged 6–14 months refused to crawl out over what looked like a sheer drop‑off – shows that newborns' fear of heights and drops emerges early.

This innate caution isn’t a cultural quirk—it’s wired into our very genes to help us survive. Tiny humans without depth perception would likely bump their heads (and worse!) far too often.Neuroscientists call it an evolutionary safety net: the fear of heights and falling prevents young adventurers from testing the very limits of gravity before they're ready. The reflex is so built‑in that even some animals—kittens, chicks, puppies—display similar hesitancy.But hold on, here’s the kicker: crawling actually triggers that fear to bloom. Babies who haven’t yet learned to crawl often don’t mind inching across the edge—but once they can crawl? A mix of experience, awareness, and motor coordination teaches them that gravity can be unforgiving. From there emerges caution—a primal, adaptive filter in the chip of our survival software.

The fear of loud noises (the ‘startle reflex’)

Did you ever jump at the sudden clang of a dropped pot or a car backfiring? That’s your acoustic startle reflex in action.

From day one, our nervous systems are tuned to flinch and duck at sharp, loud sounds.Newborns don’t stroll through a carnival and casually shrug at fireworks—they flinch. That sudden jolt? It’s our built‑in acoustic startle reflex, triggered by a noise loud enough to hint at danger: a thunderclap, a crash, a gunshot.Neuroscientist Seth Norrholm at Emory University explained to CNN that this startle response is hardwired as a danger signal—an instinctive “something’s wrong here!”—built into our primitive brain circuits, saying, “If a sound is loud enough, you’re going to duck… Loud noises typically mean startling.

That circuitry is innate.”Even infants react: a pressure‑cooker whistle can reduce a newborn to tears and frantic alarm, while a blender whirr still makes toddlers flinch. This isn’t just cute baby behavior or drama—it’s survival code.

What about the other fears? (Spiders, snakes, or public speaking?)

Well, this is where it gets fun: none of these are inborn. They’re learned. It’s all nurture after nature’s handshake.

Take the classic Little Albert experiment: baby Albert was neutral around a white rat—but after pairing the rat with a loud noise, he started fearing it.

The rat became a cue for fear. That’s classical conditioning in action—wired reflex meets learned association.Spiders and snakes? Infants may show heightened attention to images of snakes or spiders, but they don’t exhibit fear—just alertness. The leap to panic requires learning, and babies only have a predisposition to notice them faster—learning later fills in the rest.Darkness? A toddler afraid of the dark? It’s likely tangled in imagination and stories—not wiring.Public speaking, social rejection, or the fear of failure? Purely human-made constructs—taught, absorbed, amplified through culture, life experience, and sometimes trauma. The modern aphorism, “We are born with only two fears…” often pops up in self‑help, lifestyle, and pop smarty circles to empower people: if those big, paralyzing fears aren't innate, you can unlearn them.

Nature vs nurture: The endless loop

The two built-in fears fit our bodies like mission-critical apps. All others are downloadable: we install them throughout life based on experiences, culture, imagination, parental caution, news media… You name it!In fact, some experts emphasize it’s not just that learned fear crops up—it’s how easily we learn certain things.

Babies are primed to quickly associate certain threats (like heights or loud noises), while other sounds—say, the blender or the pressure cooker—get conditioned slowly. A child might hate the sound of a blender, not because of wiring, but because mom took a decade to cook with it near her ears.

As the saying goes, “the only fear we’re born with is the fear of falling. Everything else is learned…” and yes, many therapists encourage remembering that—because if we can learn fear, we can also unlearn it.That realization carries a sense of comfort. If those two fears are innate—and every other one isn’t—then we shape our fears. We also reshape them, too. No wonder therapy, exposure techniques, and heartfelt conversations can melt the chill of fear over time.So next time you’re jittery before a speech or tense over some unknown, remind yourself that fear wasn’t in your genetic blueprint. You downloaded it somewhere—and you can delete it, one step at a time.

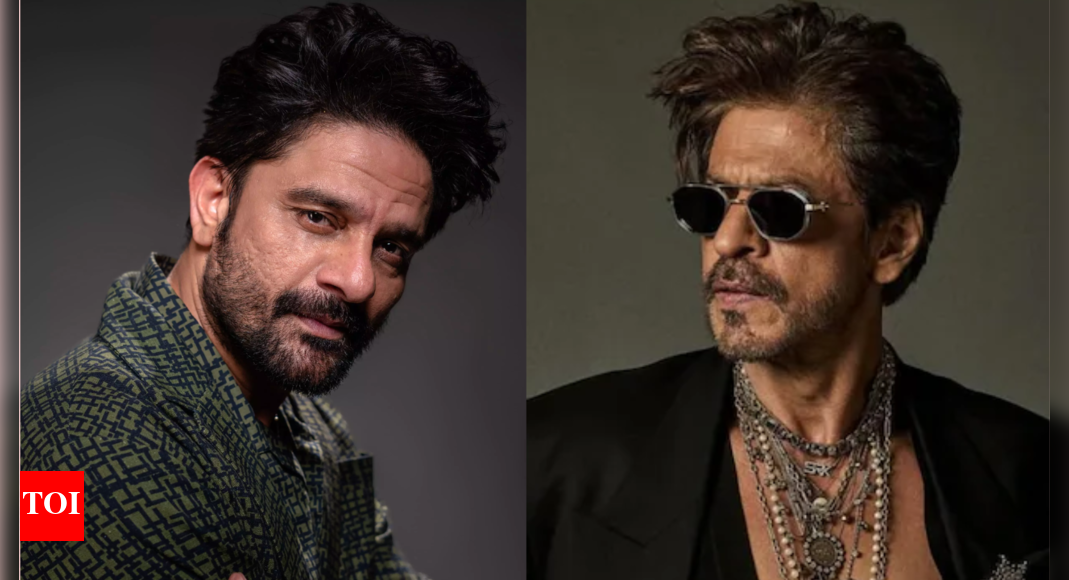

Did you know Shah Rukh Khan rejected David Dhawan's two films for this reason?

.png)

.png)

.png)

3 hours ago

5

3 hours ago

5

English (US) ·

English (US) ·