ARTICLE AD BOX

Veterans attribute the transformation of public perception largely to the Goa Konkani Akademi, which took award-winning plays from the competition directly to rural audiences

Konkani theatre’s journey has been nothing short of remarkable, evolving from the shadows of contempt and strife in the 1970s to establishing itself as a beloved institution. The once-cancelled competition has given rise to a Golden Jubilee fest this year, symbolising the renaissance of the Konkani language

When the vehicles carrying the troupe of Shree Nagesh Mahalaxmi Prasadik Natyasamaj rolled into rural Goa in 1983-84 to stage Pundalik Naik’s Pimpal Petla, they were greeted not with applause but with stones.

Tyres were punctured, abuses hurled, and the very idea of performing in Konkani was met with contempt.“It was an anti-Konkani atmosphere that prevailed then,” recalls Ajit Kerkar, the eminent theatre personality whose troupe faced the brunt. “Konkani faced calumny and ridicule in the 1970s. Konkani troupe members would be abused, stones would be pelted on their vehicles, and derided.”Half a century later, as 18 institutions converge at Rajiv Gandhi Kala Mandir, Ponda, for the Golden Jubilee edition of the competition which kicks off on Oct 27 with Mukesh Thali’s ‘Jallem’, the transformation is complete.

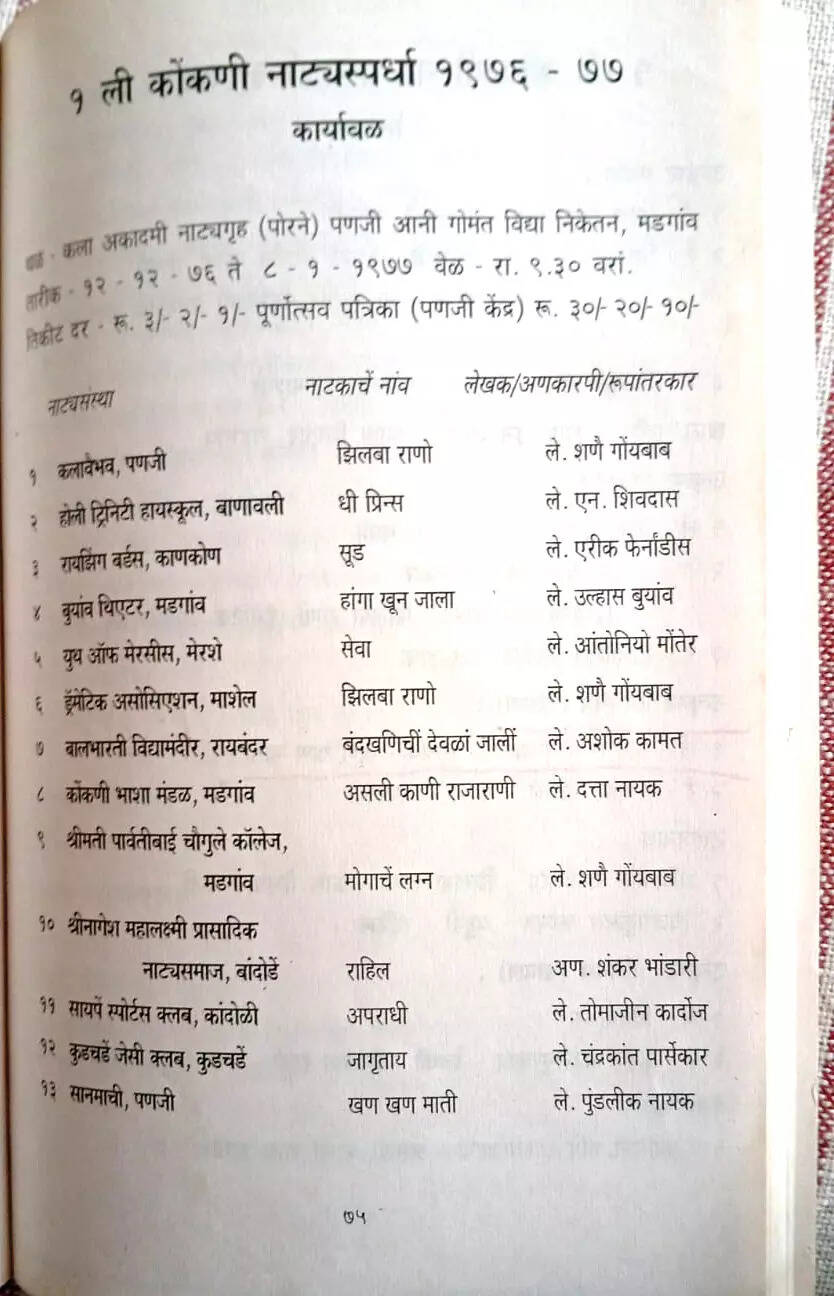

The language that once invited violence now commands respect; the art form that was scorned has become the darling of rural Goa.The journey began falteringly in 1970 when Kala Academy announced its first drama competition. The Konkani segment had to be cancelled owing to insufficient entries – it was mandatory then to have at least five entries shortlisted. It would take six years of persistence before the first Konkani drama competition finally materialised.

“The reasons were varied — lack of Konkani scripts (both original and translations) for one, dearth of trained actors for another, and the Konkani movement which was in its nascent stage demanded undivided attention,” explains Mukesh Thali, the acclaimed playwright and Sahitya Akademi awardee who will see his work open this year’s competition.“The first Konkani drama competition in 1976-77 was a milestone,” says Thali.

“It was a declaration that Konkani theatre had arrived.”He attributes this revival to veteran Konkani playwright Pundalik Naik, “who laid the foundation with plays that echoed the voice of the people. His works were raw, real, and rooted”.The timely establishment of Goa Kala Academy’s school of drama provided the infrastructure needed to nurture talent. New names marked their arrival — Dattaram Bambolkar, Prakash Vazrikar, and later Thali himself.

“The atmosphere had become conducive,” Thali says. “We began producing original works that carried the aroma of our soil — idioms and dialogues steeped in Goan culture.”

While Kerkar’s troupe has been a part of the movement since the competition’s inception, Kerkar has been a fixture since its third edition.If the early producers — Prakash Thali, Digambar Singbal, Purushottam Singbal and others — charted the roadmap, the new generation of producers like Rajdeep Naik, Prashant Satarkar, Sachin Naik and Govind Raikar further fuelled its growth, “quenching the thirst of rural audiences to laugh, to feel, and to celebrate.”Veterans attribute the transformation of public perception largely to the Goa Konkani Akademi, which took award-winning plays from the competition directly to rural audiences. Single productions now run for 100 shows during zatras, kales, and Ganeshotsav programmes. People are choosing Konkani plays over Marathi ones.“As a playwright, I feel there has to be more and more original plays which carry the aroma of the soil with idioms and dialogues that emit the fragrance of the language of the land,” Thali says.Yet Kerkar believes the bar needs to be raised, “What concerns me is the sub-standard presentation of most of the Konkani plays in the competition. Barring some 4-5 plays, the rest fall below standards.” He calls for brainstorming sessions involving the Kala Academy, the department of art and culture, and all stakeholders to understand and address the challenges faced by the artistes.

Nevertheless, optimism rings through Kerkar’s voice when he says, “We have achieved such heights that we can effectively hold our own against the best—Marathi and Bangla theatre, long regarded as the benchmarks of Indian theatrical tradition.

The competition has matured over 50 years. The next half-century will be our flowering period—the groundwork is done, the talent exists, now it’s about consistent excellence.

”Kerkar succinctly sums up the aspirations of a Konkani natya mogi, “If Konkani theatre has conquered hearts at the state-level, global recognition is inevitable. To put it simply, it’s already been crowned Miss Goa, the Miss Universe crown awaits.”

2 hours ago

6

2 hours ago

6

English (US) ·

English (US) ·