ARTICLE AD BOX

In 2019, mushrooms briefly turned Arpit Dhupar’s life upside down—just when he had hoped to earn from them. “I had quit as Chief Technology Officer at Chakra Innovation and invested around Rs 7–8 lakhs in an oyster mushroom farm, because mushrooms were then the rage.

Everyone in South Delhi was buying them,” he recalls. His plan: rent a house in West Delhi, grow oyster mushrooms, and sell them at INA Market. But fungal contamination—green and black mould—ruined the idea. “And so, I decided to cultivate a genetically superior mushroom strain that wouldn’t get contaminated,” says the mechanical engineer.He found lab space at the Regional Centre for Biotechnology in Faridabad and started to research the fungus.

“I realised that eating mushrooms was underutilising their potential... Then I came across biofabrication and knew that was what I really wanted to do.” He began cultivating mycelium—the root system of mushrooms— on paddy straw waste to create a biomaterial thatpossessed all the properties of expanded polystyrene foam, but with an additional one, compostability.

Put simply, he developed a sustainable alternative to thermocol.

Today, Dharaksha Ecosolutions, which Dhupar co-founded, supplies mycelium-and-crop stubble packaging to companies like Dabur and Havells. “When we started, we processed 100 kg of feedstock in 3–4 months,” he says. “We now process 100 kg a day.”Dhupar is part of a growing group of material science entrepreneurs replacing single-use plastics (SUPs) with sustainable bio-based alternatives. SUPs—carry bags, food containers, ecommerce packaging—are high-volume, low-recyclability products with significant environmental and climate impacts.

Packaging alone accounts for 56% of India’s plastic consumption, with 95% discarded after short use, according to Saahas, a waste management nonprofit.

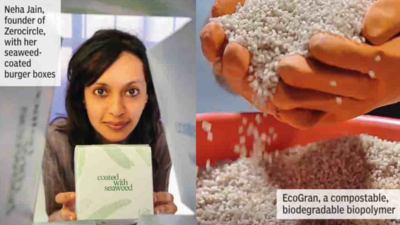

And packaging is what new companies are focusing on.Derived from organic matter such as mushrooms, crop stubble, and seaweed, these alternative materials are making small but keen inroads into the Indian market, with plans to go deep and wide.To Market, To MarketOn May 28—International Burger Day—Swiggy cus-tomers in Bangalore, Mumbai, and Delhi noticed something unusual on their burger boxes: a label reading “coated with seaweed”.

The algae wasn’t on the food—it was part of the box, made by Zerocircle, a Pune-based startup that partnered with Swiggy to launch its sustainable food packaging. Founded in 2020, Zerocircle makes seaweed-based films, pellets, and coatings that render paper packaging grease- and leak-proof.

Their products are also “microplastics-free, home-compostable, and ocean-degradable”.Founder Neha Jain credits growing consumer awareness.

“The success with the Swiggy partnership is largely because consumers are constantlytalking about microplastics in food... That is why we have come this far without subsidies or big pushes from govt, brands, or manufacturers,” she says. Venture capital, grants and awards have played a key role. Zerocircle raised Rs 20 crore this year; Dharaksha, Rs 24.8 crore in 2024; and Faridabad-based Ukhi, Rs 7.7 crore last year.

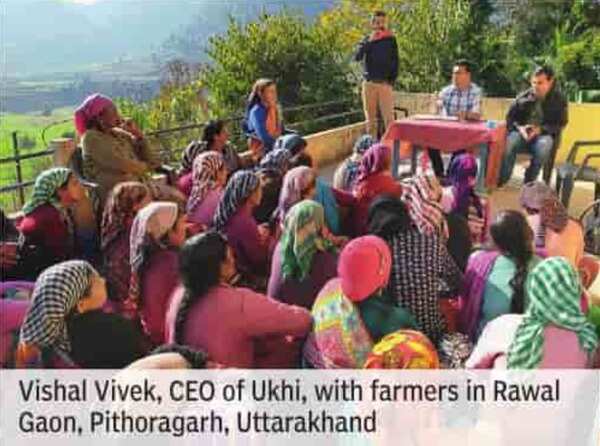

Ukhi converts rice husk, hemp, nettle stems, and pine needles into EcoGran, a compostable, biodegradable biopolymer for flexible packaging—used in garbage bags, e-commerce mailers, and shrink wrap. “Flexible packaging accounts for a quarter of the 200 million tons of single-use plastics produced globally,” says Vishal Vivek, CEO and co-founder of Ukhi.“In six years, we’ve worked with over 100 farmers. But we need many more—our new facility will require 500 tons of agriwaste a year.”

How To Scale

Sixty per cent of Ukhi’s clients—including Ralph Lauren—are international. For Zerocircle, it’s 90%. That’s partly due to global market maturity and partly to cost. “Globally, we are 50% cheaper than other natural polymers companies,” says Jain. In India, sustainable packaging alternatives remain niche—awareness is low and costs can be 3–5 times higher than SUPs.“Alternative materials are inherently costlier than their crude-based counterparts because the fossil fuel industry has been around for over a hundred years and has been optimised and scaled significantly,” explains Dhupar.

“Once we scale, have 10–20 large customers, and industry bodies issue stricter mandates to use alternative materials, things will start to accelerate,” he adds.In 2021, Confederation of Indian Industry (CII) launched the India Plastics Pact, a platform to helpbusinesses make the transition to a circular economy for plastic packaging. The first of its four targets is to redesign and innovate for problematic plastic packaging.

However, a CII spokesperson notes that while alternatives are key for certain applications, they won’t solve all industrial packaging needs.

Sarkari Support

Founders agree that while direct govt support for alternative materials has been limited, plastic regulations have helped indirectly.In July 2022, the govt banned 19 low-utility, highlitter SUP items like plastic straws and carry bags thinner than 120 microns. Though the broader policy still focuses on reducing, reusing, and recycling plastic, these bans are nudging consumers toward alternatives.

“It will take time but gradually bioplastics like ours will become one of the substitutes to plastics,” says Vivek. “They may never replace everything plastic, but they will replace a larger share of what’s now in the market.

”Another key policy may help lower costs. The revised Extended Producer Responsibility (EPR) mandate requires a minimum amount of recycled plastic in packaging from April 1, 2025. “This is going to be a major lever, because EPR has been a significant promoter of alternative materials in the West,” says Dhupar.

“We can’t compete on price, so there has to be a value proposition. EPR makes that stronger. If recycled plastic adds 10–15% to brandcosts, they might as well invest 20–25% in safer, more sustainable materials that offer a better marketing story.

That’s what will bridge the gap.”

Need Of The Hour

Not everyone can make the switch at once. “Street vendors, small shops, and others in the informal economy don’t have the leverage to buy alternatives to single-use items.

It’s therefore a question of the economic viability of these alternatives,” says Swati Sambyal, Senior Circular Economy Expert at GRID-Arendal. “Will Rs 100, that can buy say 400 or 500 plastic carry bags, buy the equivalent number of sustainable alternatives? Therefore, the social, economic and environmental viability of alternatives of SUPs have to be looked at together.

We must make alternatives cheaper and develop mechanisms to make it happen.”But cost isn’t the only challenge. “We also need clear enforceable standards for alternatives and investment in waste infrastructure that can handle these new waste streams,” Sambyal adds. She points out that alternative materials should besorted separately from dry and wet waste, as they can contaminate recycling streams. For example, if recyclers misidentify mycelium-based packaging and send it for dry waste processing, it could compromise the quality of recycled granules.Labelling is also essential. The alternatives market includes diverse materials with different chemical makeup, and the “bio” label can be misleading. “For instance, you may start out with agriculturally produced biomass, like bagasse or corn, and polymerise it with synthetic compounds for additional properties like elasticity or strength. But when it breaks down, it will leave those synthetic chemicals behind,” says Jain.

“Just because it comes from a plant source doesn’t make it better.”The same goes for biodegradability and compostability. “Biodegradable does not mean degradation like a vegetable,” she continues. “The product doesn’t disappear but only breaks down into smaller fragments. In the same way, compostable plastics, such as bin liners, can only be industrially composted, which means 60 degrees of heat and industrial infrastructure.

So, the first thing we need to do is identify standards that differentiate different materials and their end-of-life based on the infrastructure that exists.

”Startups are working to build awareness but often must begin at the most basic level. “People start the conversation with, ‘Is your solution green?’,” says Jain, “And I’m like, ‘Okay, we have to really break this down’.”

When Vinay Balakrishnan launched his edible wheat bran plates in 2021, it was Europe that showed interest.

“Indian consumers want aesthetics, not sustainability,” says the Coimbatore-basedentrepreneur.Today, his brand Thooshan exports crop-based crockery to seven countries, though the business has been running at a loss. This year, he hopes to break even, thanks to orders from Switzerland and Mexico.“Last year, it took the Swiss six months to clear the streets of discarded Christmas trees when the season ended,” he says.

This year, Thooshan was tasked with turning that waste into biodegradable tableware.In Mexico, he is turning Agave tequilana—the tequila plant—into cutlery. “They export tequila but are left with tonnes of cactus waste.”I’ve had my eye on all kinds of agri-waste,” says Balakrishnan. “Corn and wheat from the US, rice husk from Argentina, date seeds from the UAE, and oil cake waste from canola and mustard in Canada. My goal is to turn this waste into sustainable products and reduce single-use plastic.” —Kamini Mathai

Get the latest lifestyle updates on Times of India, along with Eid wishes, messages, and quotes !

.png)

.png)

.png)

15 hours ago

3

15 hours ago

3

English (US) ·

English (US) ·