India’s Operation Sindoor in the wake of the Pahalgam terror attack has marked a notable shift in the country’s adoption of Unmanned Aerial Vehicles (UAVs) in combat. In combination with standoff weapons, India’s use of UAVs in active combat represents a tactical shift in military doctrine — part of a global playbook. Ukraine’s Operation Spider Web also marks a turning point in how low-cost, improvised unmanned systems can be employed with strategic impact.

Global precedents

The ubiquitous drone is rapidly becoming the weapon of choice serving as a force multiplier to achieve strategic objectives while blurring the distinctions between military-grade and commercial technologies. Building resilience in drone warfare requires India to build modularity and redundancy in mass produced drones, and nurture a responsive defence production base.

The Nagorno-Karabakh War in 2020 provided one of the first demonstrations of how drones can change the nature of aerial warfare with new capabilities. Azerbaijan’s success hinged on the use of loitering munitions or Kamikaze drones, like the Israeli-made Harop drones, in destroying air defences.

Additionally, the war in Ukraine has emerged as a real-world laboratory for drone technology, with rapid innovation and counter innovation cycles defining modern warfare. However, Ukraine’s most obvious innovation was the country’s ability to produce and deploy a wide variety of drones. In Myanmar also, rebel groups are deploying 3D-printed drones against a better-equipped military, levelling the playing field.

As India continues to reform and modernise its military, learning and applying the right lessons from recent conflicts, including Operation Sindoor, is key. Among New Delhi’s adversaries, China already has a large and diverse fleet of unmanned systems, which could provide it with an edge in a potential war along the Line of Actual Control (LAC). Pakistan too has bolstered its unmanned weapons capabilities through collaborations with China and Türkiye.

Drone resilience

Drones are vulnerable to many countermeasures such as electronic warfare, guns and air defences. The impact of drones, therefore, depends on its ability to evade or overwhelm defences against them.

Countermeasures against drones in the form of air defences come with limitations and vulnerabilities and can be defeated through a range of technologies and tactics, making innovation and counter-innovation a critical part of drone warfare. India’s counter-drone systems include multilayered sensors and weapon systems, as well as indigenously developed soft- and hard-kill counter-UAV systems. Both played a crucial role in thwarting Pakistan’s drone and missile attacks in the recent flareup of hostilities.

To evade such systems, drones can, with advanced navigation, be made to adjust flights. Similarly, Artificial Intelligence (AI) and frequency hopping can be used to overcome jamming and spoofing autonomously. For instance, Ukraine has incorporated machine vision algorithms and pre-loaded terrain data to navigate complex routes in order to avoid air defences. By operating at low altitudes, drones can exploit gaps in radar coverage and reduce the likelihood of detection.

Some drones are also designed with electronic warfare features, allowing them to jam or spoof enemy radar and communication systems. These capabilities enhance their survivability and effectiveness in contested environments. Ukrainian developers came up with a simpler solution — tethering a drone to a fibre-optic cable for guidance.

Alternatively, employing a large number of drones and decoys to fly in mass can overwhelm and confuse air defence and surveillance systems. Russia’s drone campaign, for instance, makes use of Shahed drones to saturate Ukrainian air defences. It causes dilemmas on the rate of attrition of limited air defence assets, and creates openings for precision strikes.

India’s air defence systems tied together under the Integrated Air Command and Control System (IACCS) performed well against numerous Pakistani drones and missile attacks. Boosting procurement and domestic production of munition stocks for its air defence systems (S-400, MR-SAM, Akash, etc) will be key to building magazine depth in any protracted conflict. With regard to the offence debate, given the low survivability rate of current drones, India will need to invest in building volume in its drone and loitering munitions toolkit.

The military-commercial crossover

Ukraine’s Operation Spider Web demonstrated that low-cost UAV’s combined with accessible technologies and innovative employment strategies can have strategic impact deep into enemy lines. The operation targeted four air bases inflicting damage to Russia’s long-range bomber fleet.

The fact that almost any drone can be used and modified to become an offensive weapon, coupled with the widespread use and accessibility of drones, has blurred the distinctions between military-grade and commercial drone systems. Moreover, the indiscriminate use of the term “drones” obscures distinctions in capabilities, intended uses and public perception.

While advanced military-grade drones offer greater capabilities, they also come with higher costs and logistical challenges. Easily available commercial systems, open-source software, and modular engineering have lowered the entry barrier for the adoption of drone technologies. There is a trade-off between adding capabilities to drones and an increase in cost, size, and complexity. For example, drones such as China’s Wing Loong, Iran’s Shahed, or Turkey’s TB-2 incorporate low-cost and dual-use technologies.

Innovation in technology has not been the only novelty in drone use, for manufacturing has also changed. 3D printing is rapidly becoming a key multiplier. For instance, in conflict zones such as Ukraine (Titan Falcon) and Myanmar (The Liberator MK1 and MK2) 3D printers provide alternate sources to mitigate manufacturing shortages. The adaptive employment of off-the-shelf drone technologies by non-state actors is providing states with valuable lessons in asymmetric and low cost aerial capabilities. For example, the U.S. and the U.K. are exploring commercial 3D printing ventures to mass produce drones at scale in order to manufacture bespoke components of weapons systems, thereby bypassing complex, expensive and often slow moving logistics supply chains.

India needs to prepare for the inevitability of easily weaponised commercial drones being used by terrorist organisations and non-state actors against its strategic and civil infrastructure. Counter-drone systems and tactics cannot be the purview of the military alone and should also be prioritised by internal security agencies.

Implications for India

The widespread adoption of drones in warfare signifies a shift in military strategy and operations. By deploying standoff weapons along with drones during Operation Sindoor, India has introduced a layer of strategic ambiguity — one that expands its toolkit vis-a-vis Pakistan in the space between conventional and nuclear. Meanwhile, China’s export of drones, among other platforms, to Pakistan adds a layer of complexity to India’s security challenge.

China’s own drone capabilities are rapidly advancing as significant investments have been made in building up a diverse fleet of drones, including long-range systems like the Soaring Dragon, BZK-005, TB-001, and Wing Loong II alongside affordable kamikaze drones, like the CH-901, designed to overwhelm enemy defences through swarm tactics. This poses a significant and evolving military threat to India along the LAC.

For India, drones complement other weapons and can partially offset capability gaps as part of an asymmetric defence strategy vis-à-vis China. However, India needs to view the wars in Ukraine, Nagorno-Karabakh, and Myanmar as cautionary tales for the need to mass produce an affordable mix of drones.

Of the many lessons from the ongoing war in Ukraine, one stands out — the importance of a defence industrial base that can keep pace with the high-intensity of modern conflict. To fully realise India’s drone potential, the Ministry of Defence (MoD) needs to support the defence industrial base to be able to scale production and create surge capacity. The ability to reconstitute and quickly replace drones, loitering munitions after losses, and surface-to-air missiles will make India more resilient.

India’s anaemic procurement of systems has generally discouraged industry from ramping up its production capacity.

Addressing underlying structural issues that lead to uncertain demand is key in order to incentivise industry to ramp up production capacity and innovation in defence.

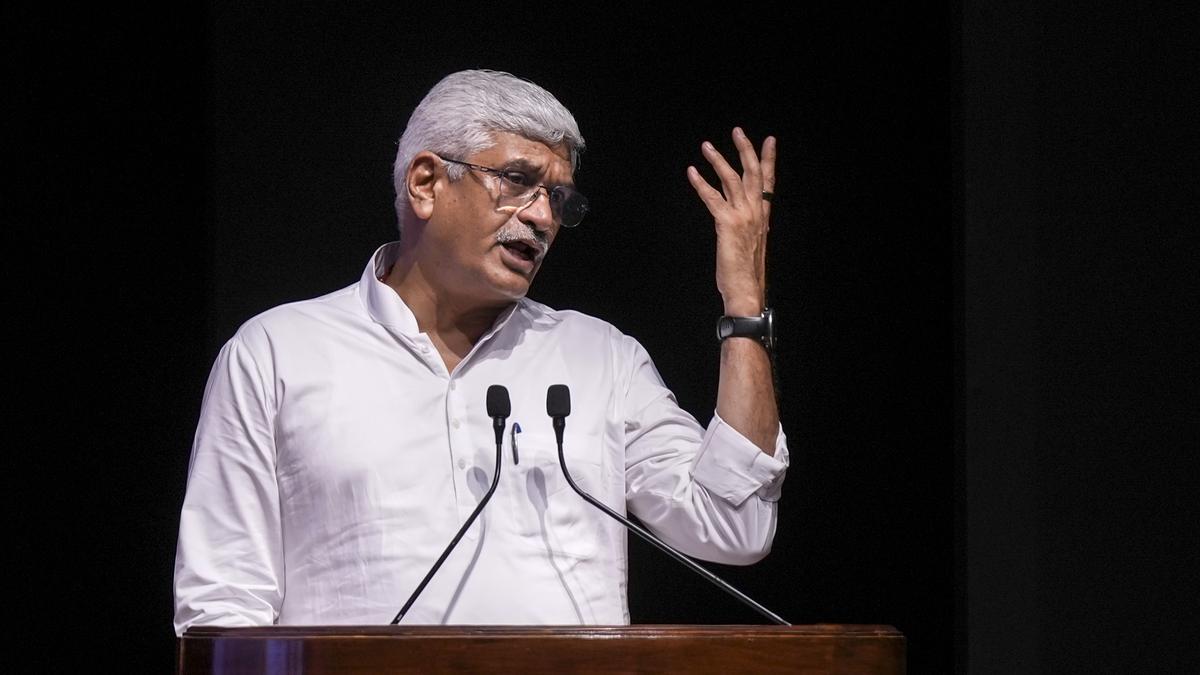

Pushan Das is a strategic affairs analyst who writes on defence and foreign policy.

Published - June 10, 2025 08:30 am IST

.png)

.png)

.png)

5 hours ago

7

5 hours ago

7

English (US) ·

English (US) ·