ARTICLE AD BOX

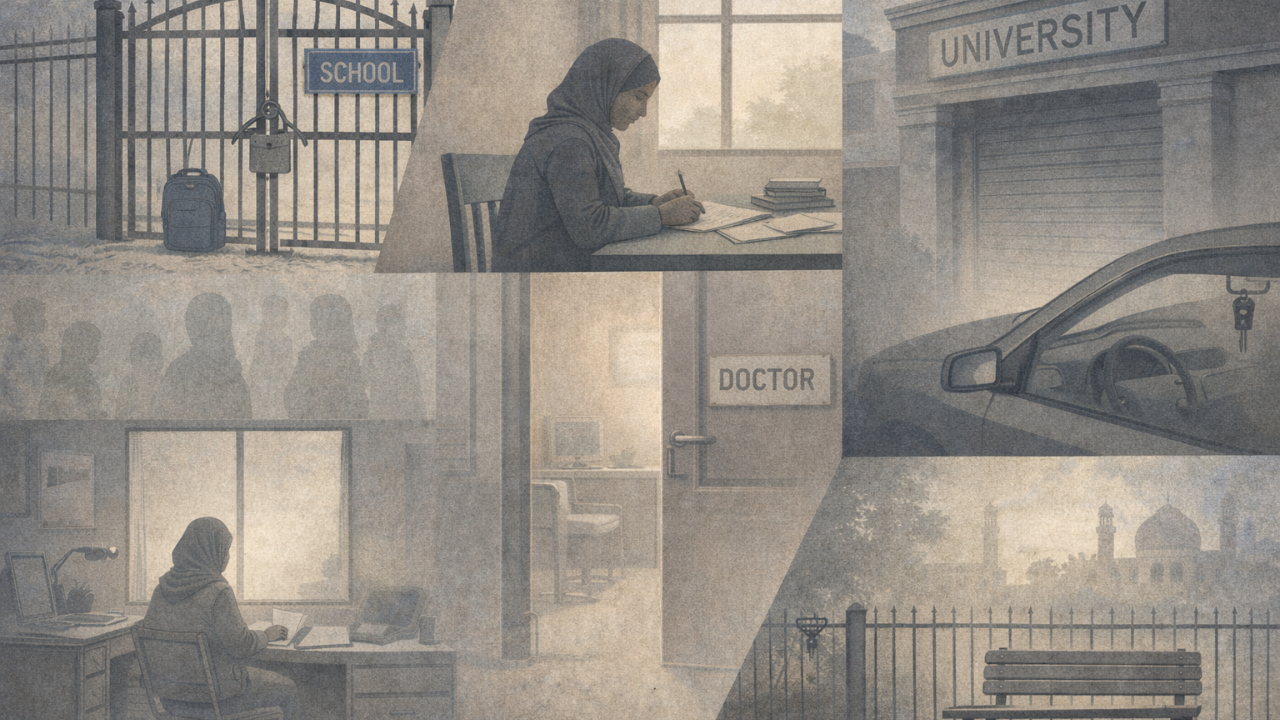

When the Taliban returned to power in August 2021, it did not simply change the flag over Kabul. It altered the everyday world of Afghan women in a way that is now hard to comprehend from outside the country.

As Afghanistan approaches five years under Taliban rule, directives issued by the de facto authorities have steadily turned basic freedoms into privileges.Girls are barred from secondary school. Women are shut out of universities. Most jobs are off-limits. Public spaces such as parks, gyms and sports clubs have become no-go zones. The impact is not only a loss of opportunity, but a shrinking of public existence itself.

Image: AP

Rights curtailed amid economic collapse

This transformation has unfolded amid a worsening humanitarian crisis. Poverty has deepened, food prices have risen, and families are increasingly forced to choose between education and survival. With women largely excluded from paid work, households have lost a critical source of income, pushing many deeper into dependence on aid and informal labour.

Image: AP

In such conditions, restrictions on women and girls are not only a matter of rights; they are also a matter of survival.

And because Afghanistan has been largely cut off from independent reporting, the true scale of this hardship remains difficult to measure.

Women in Afghanistan: Not always invisible

Afghanistan’s history, however, is not solely a record of repression. It is also a history of women who resisted, sometimes quietly and sometimes openly, even when the odds were stacked heavily against them. Long before the modern nation-state, the region was shaped by successive empires and cultures, each leaving behind traces of women’s influence.While historical records rarely document women’s daily lives, figures such as Rabia Balkhi, Queen Goharshad, Malika-i-Jahan and Shah Bibi still surface as reminders that women were not always invisible.

Newly trained women officers of the Afghan National Army sit in the front rows during a graduation ceremony for a fresh batch of recruits at the Army’s training centre in Kabul on September 23, 2010. (Image: AP)

Progress, then reversal

Even so, for most Afghan women, life has long been shaped by conservative social norms. Education was difficult to access, and employment even harder. Many women were confined to the home, and legal systems offered little protection against forced marriages or unequal inheritance.

In such a landscape, the achievements of a few women stood out precisely because they were rare.In the two decades following the Taliban’s ouster in 2001, there were moments when Afghan women appeared to be moving forward. They entered classrooms, offices and political spaces in growing numbers. For a time, there was cautious optimism that gradual change was possible.

AI generated image

That progress, however fragile, was abruptly reversed in August 2021.

What has been lost since is not only education or employment, but the very sense of being present in public life.

Quiet resilience in shrinking spaces

Today, Afghan women live under layers of restriction and uncertainty. Yet accounts emerging from inside the country point to quiet determination. Women barred from school still find ways to learn. Those excluded from work search for informal means to support their families.In a society where public space has narrowed, private resilience has become a form of resistance.Some Afghan women have managed to leave. They are now scattered across Europe, West and South Asia, Australia and North America, living under vastly different conditions of safety, legality and survival. For some, escape has brought a fragile form of freedom. For many others, it has merely replaced one kind of uncertainty with another.

Image: AP

India is among the countries hosting Afghan refugees who are trying to survive and rebuild their lives despite significant obstacles.“They faced tremendous hardships back home. That’s why they are here,” said Shivani (name changed), who runs an NGO in Delhi that helps Afghan women find livelihoods.“Even after leaving their country, wherever they go, they continue to face difficulties. They are stripped of their identity, and there is no strong support system they can rely on,” she said.Afghan refugees approached by The Times of India declined to comment.

Shivani suggested their reluctance reflected fear. “They need to earn a living and continue to stay here without attracting further problems,” she said.

‘Morality’ as control

In Afghanistan, the language of “morality” has long been used as a tool of social control, and it has almost always fallen hardest on women and girls. Ideas of honour, dignity and family pride are placed on women’s bodies and behaviour, turning them into symbols rather than individuals.

Women are often defined not by who they are, but by who they belong to — a mother, wife, sister or daughter.

Image: AP

When authorities speak of “immorality”, it is usually women who are judged, blamed or punished. This framing has shaped policy and policing for decades, well before the Taliban’s return.The Taliban justify these restrictions as rooted in their interpretation of Islamic law and Afghan culture, arguing that such measures preserve morality and social order.

Rights groups and religious scholars have repeatedly contested this interpretation.

From first rule to return

The Taliban first emerged in 1994 amid the chaos that followed years of war. Many of its members were former mujahideen fighters trained during the Afghan conflict of the 1980s and 1990s. The group promised order through the creation of an Islamic state and went on to rule Afghanistan from 1996 to 2001 — a period marked by severe restrictions on women and girls, including bans on education and employment.After the Taliban were ousted in late 2001, improving the lives of Afghan women became a central argument used by Western leaders to justify military intervention. While this focus drew attention to gender rights, it also produced a patronising narrative that portrayed Afghan women solely as victims in need of rescue.

Image: AP

There was little sustained engagement with how prolonged conflict, displacement and insecurity shaped women’s daily lives.Progress did follow in some areas, particularly in education and political participation, but discrimination remained deeply embedded. In 2011, Afghanistan was ranked among the most dangerous countries in the world to be a woman — a reminder of how fragile those gains were.

Rollback after 2021

When the Taliban returned to power in August 2021, the rollback was swift. Despite early claims of moderation, restrictions tightened almost immediately.

Women took to the streets to protest, demanding the right to work and study.The response was harsh. Demonstrators were beaten, detained and, in some cases, killed. Among them was former parliamentarian and women’s rights advocate Mursal Nabizada, whose death became a symbol of the risks faced by women who remained visible in public life.

Image: AP

Since then, the space for women has steadily shrunk. Girls have been barred from secondary schools.

Women are excluded from universities and most forms of employment. They face restrictions on movement and are prohibited from accessing public spaces such as parks and gyms.Each rule may appear administrative on its own. Together, they amount to a systematic removal of women from public and social life.

What happens when there is no safe way out

Healthcare under constraint

For much of the past two decades, Afghanistan’s basic services relied heavily on international donor funding, particularly in healthcare.

That support has declined sharply. The United States, long the country’s largest donor, accounted for about 43% of all aid to Afghanistan in 2024, largely in the form of humanitarian assistance.The Trump administration has since justified cutting back funding by citing concerns that aid was benefiting terrorist groups, including the Taliban. US officials have also said they received reports suggesting at least $11 million was being siphoned off.

Image: AP

The reduction in assistance has come at a time when Afghan women are already bearing the brunt of political and social restrictions. Nowhere is this more visible than in access to healthcare, particularly reproductive care.

Abortion in Afghanistan is illegal, and women seeking it risk imprisonment.

Unsafe choices

Bahara, a mother of four, learned this when she was four months pregnant. When she asked for an abortion at a Kabul hospital, a doctor told her it was not permitted. With no legal alternatives, she turned to a neighbour’s advice and drank a herbal tea believed to induce contractions.

Image: AP

The consequences were severe. Bahara began bleeding heavily and returned to hospital, where doctors removed the remains of the fetus. “Since then I have felt very weak,” she was quoted as saying by AFP.Medical experts warn that such methods are dangerous. An incorrect dose can lead to organ damage and severe haemorrhaging. Yet women continue to resort to them in the absence of safe care.

A country without classrooms for girls

Education ends at grade six

Afghanistan is now the only country in the world where women and girls are barred from secondary and higher education.

Since September 2021, girls have been banned from attending secondary school. For many, education ends after grade six.

Image: AP

Nearly 30% of Afghan girls never enrol in primary school at all. Poverty, safety concerns and restrictive norms keep families from sending daughters to class. Child marriage has increased as families struggle to cope.

Broken promises

The Taliban initially claimed the ban would be temporary. More than three years later, schools remain closed.Informal classes and online learning operate discreetly but reach only a fraction of those affected. Denying girls secondary education is estimated to cost Afghanistan about 2.5% of GDP annually.

AI generated image

In the absence of formal schooling, madrassas have become the only option for many. A January 2025 report by the Afghanistan Centre for Human Rights alleged that extremist content has been incorporated into curricula, promoting Taliban ideology and restricting interaction between men and women.

Driver’s licences and the policing of movement

Who gets to move

Since 2021, women have been unable to obtain driving licences, though a small number continue to drive. Nargis, who works with an NGO, described repeated harassment while attempting to renew hers.Officials demanded a male guardian. She was stopped, questioned, detained and forced to hand over control of her car to her husband. Taliban authorities have confirmed that no licences have been issued to women in three years.

Image: AP

Taxi drivers can be punished for transporting unaccompanied women.Public space has become a site of constant surveillance, where routine movement can invite scrutiny, detention or punishment.

What remains

For Afghan women today, life is marked by what has been taken away — schools, work, mobility and legal protection. Yet many continue to act quietly. Some teach girls in private homes. Others document abuses or focus on keeping their families afloat.They are not absent because they have disappeared, but because the space to exist publicly has been systematically erased.

2 hours ago

4

2 hours ago

4

English (US) ·

English (US) ·