ARTICLE AD BOX

When a nearly 14-foot-long painting by M. F. Husain crossed the auction block in New York, it didn’t just make headlines; it quietly rewrote the narrative of Indian modern art on the global stage.

Monumental in both scale and vision, the painting captures the rhythm of rural India with sweeping confidence and unmistakable boldness. The work, known as Gram Yatra, sold for an astonishing ₹115 crore (around $13.8 million), becoming the most expensive Indian painting ever sold at auction. But the identity of the buyer adds another powerful layer to this historic sale. Scroll down to read more. The question that followed was inevitable: Who bought it? While the auction house maintained formal discretion, multiple art-world reports and industry insiders widely believe that the buyer is Kiran Nadar, acquiring the masterpiece for the Kiran Nadar Museum of Art.

As one of India’s most influential art patrons, Kiran Nadar also has consistently spoken about art as a public good rather than a private asset. In an interview with Financial Express, she once said, “Art must be appreciated daily, not locked away as an investment.

” The purchase, if confirmed in the long term, marks not just a record-breaking sale but a cultural moment with lasting implications for how Indian art is valued, preserved, and seen globally.

The painting that changed the price ceiling

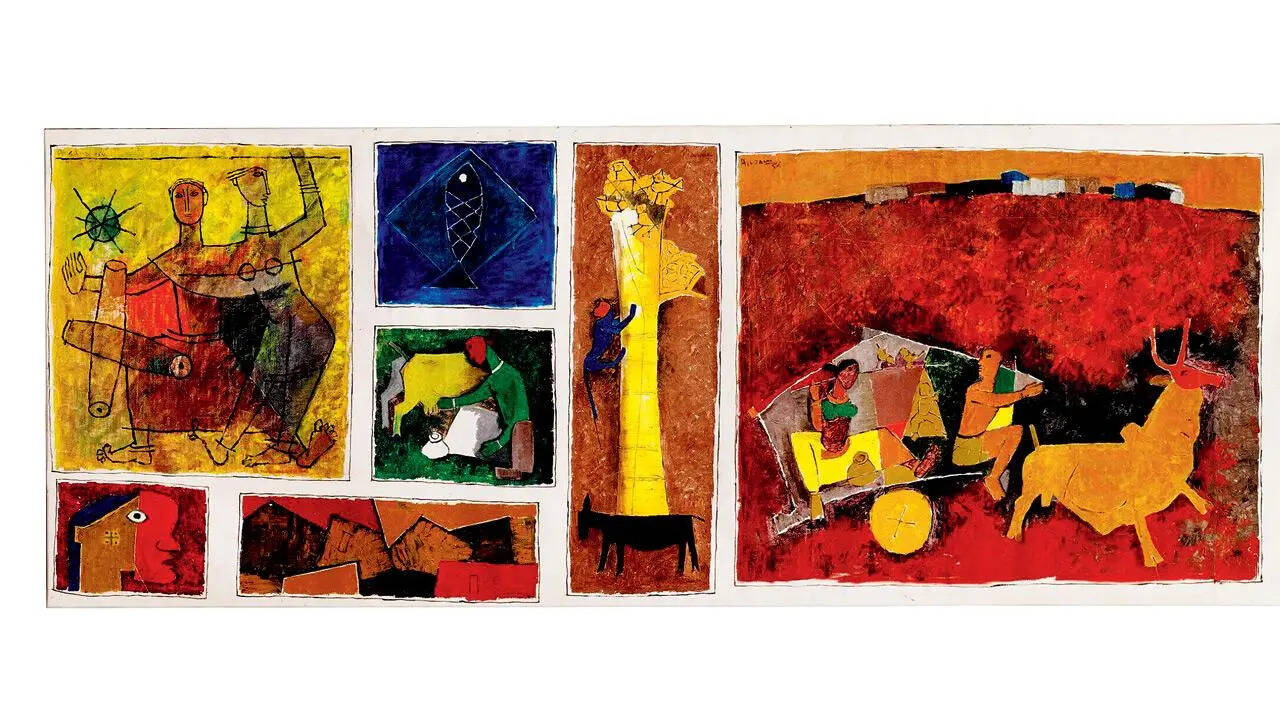

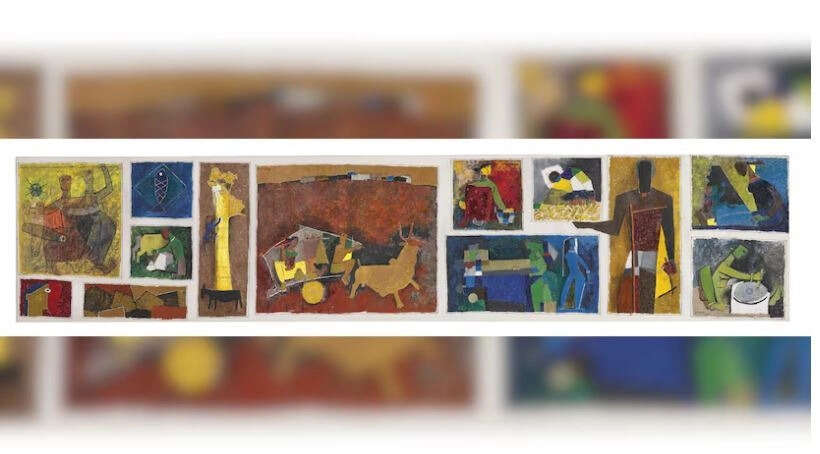

Painted in 1954, Gram Yatra is an early and ambitious work from Husain’s career, a time when India itself was still negotiating its post-independence identity. Unlike his later, more explosive canvases filled with mythological references and bold abstraction, this work is quiet, grounded, and panoramic. The painting unfolds as a sequence of 13 interconnected panels, depicting rural Indian life: farmers, women, animals, village rituals, moments of labour and rest.

There is no central hero, no dramatic climax. Instead, the painting moves like a journey, which is exactly what the title suggests. It is India observed from within, not romanticized, not distant. Art historians have long considered this period of Husain’s work to be among his most sincere and socially rooted. The scale of Gram Yatra makes it even more unusual. It is less a single painting and more a visual archive, a mural that captures a disappearing rhythm of life. Lost for decades, rediscovered by chance Part of what fueled the painting’s mystique is its extraordinary journey.

Shortly after it was completed, Gram Yatra was purchased by a European doctor working in India in the 1950s. Years later, the work was donated to a hospital in Norway, where it remained largely unseen by the public for decades. For almost 70 years, the painting existed outside the mainstream narrative of Indian modern art, referenced occasionally in scholarship but never visible enough to become iconic. Its resurfacing in recent years came as a revelation. When the painting entered the catalogue of Christie’s, it was immediately clear that this was not just another Husain; it was a historical recovery. A sale that stunned the art market Christie’s had estimated the painting at a fraction of what it eventually sold for. But once bidding began, expectations dissolved. The final hammer price was nearly four times the upper estimate, shattering previous records for Indian art. This wasn’t simply about Husain’s fame. It was about rarity, scale, provenance, and timing. Global collectors and institutions are increasingly looking beyond Western modernism, seeking narratives from Asia, Africa, and Latin America that were historically underrepresented. Gram Yatra arrived at exactly the right moment, and the market responded with unprecedented force. Who is believed to have bought it Officially, the buyer was listed only as “an institution.” That language matters. It signals public access, long-term stewardship, and curatorial intent, not private indulgence. Within days of the sale, reports across Indian and international media converged on one name: Kiran Nadar. As one of India’s most influential art patrons and the founder of KNMA, her collecting philosophy has consistently prioritized public engagement over private ownership.

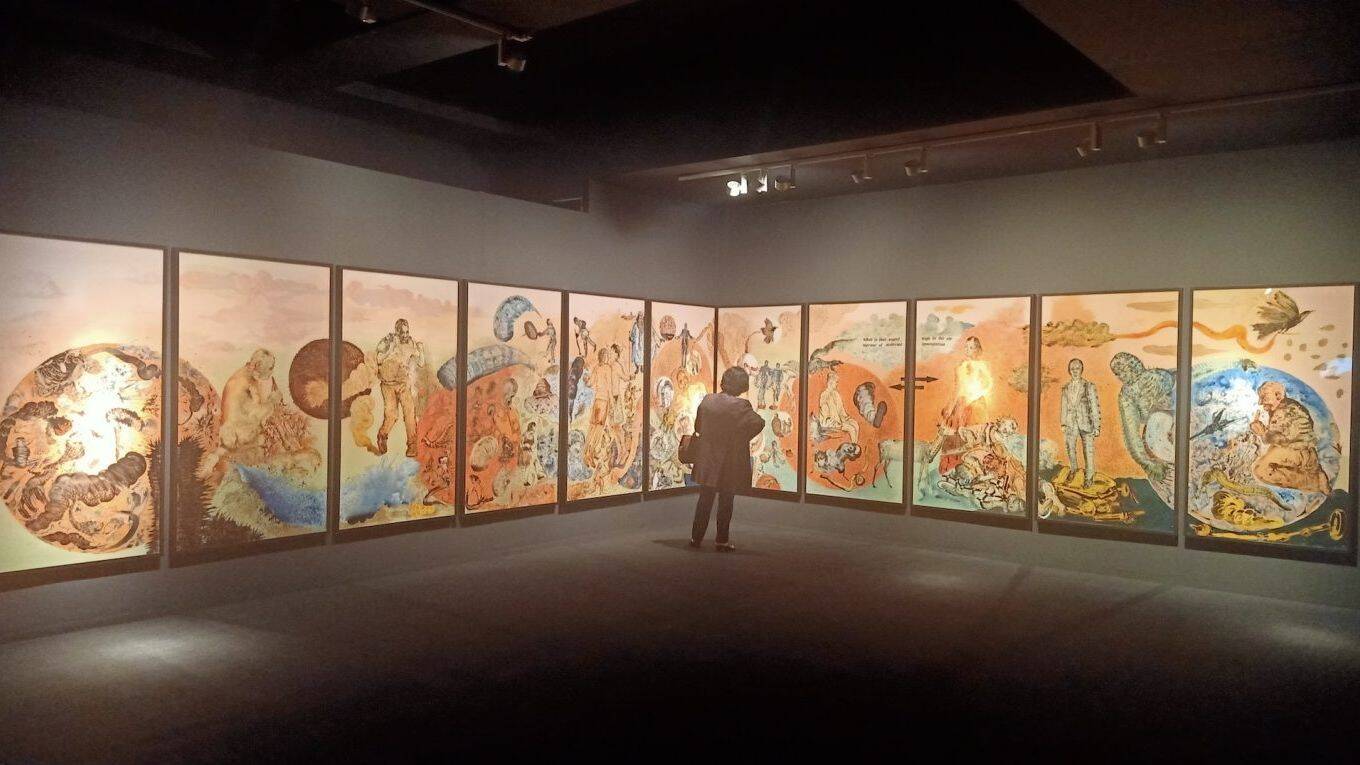

KNMA already houses one of the world’s most significant collections of modern and contemporary Indian art. Acquiring Gram Yatra would be a natural extension of its mission: to tell a complete, rigorous story of Indian art history, anchored by museum-grade works. While neither Nadar nor Christie’s issued a detailed public confirmation at the time, the consensus within the art community has been strong. Why this purchase is culturally significant If Gram Yatra does indeed enter a public museum collection in India, the implications are profound.

First, it brings home a foundational work of Indian modernism, one that was created in India, inspired by Indian life, yet spent most of its existence abroad. Second, it ensures scholarly access. Students, researchers, and future artists will be able to engage with the work not as a legend, but as a lived visual experience. And third, it resets expectations. Indian art is no longer being measured by regional benchmarks. It is competing and winning on the global stage. What this means for MF Husain’s legacy Speaking about the importance of building museum-grade collections, Kiran Nadar said in an interview with The Hindu, “A country understands itself better when it preserves and studies its art seriously.” The remark resonates strongly in the context of M. F. Husain, one of India’s most celebrated and often contested artistic figures.

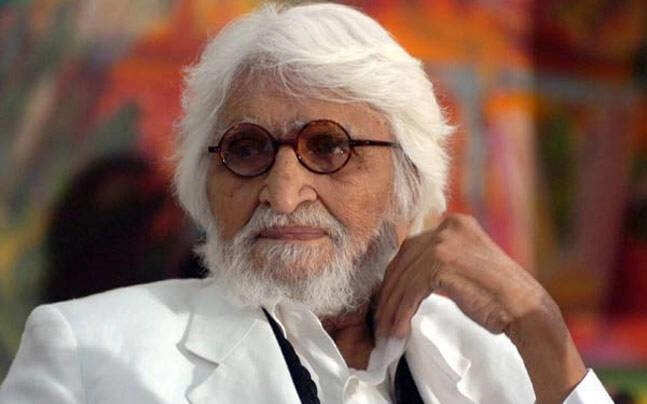

In his later years, debates around freedom of expression often overshadowed discussions of his artistic brilliance.

Sales like Gram Yatra re-anchor the conversation where it belongs, on his contribution to visual language, narrative form, and national identity. This painting reminds the world that before controversy, before exile, and before the headlines, there was a young artist trying to paint the soul of a newly independent country.A turning point for Indian art Gram Yatra is not just the most expensive Indian painting ever sold. It is a signal. It signals that Indian modern art has entered a new phase of global recognition. It signals that museums, not just private collectors, are willing to make bold financial commitments. And it signals that stories rooted in villages, memory, and everyday life can command the same reverence and value as any Western masterpiece. In that sense, the real buyer of Gram Yatra may not be a single institution at all.

It may be history itself, finally ready to acknowledge what Indian art has always been worth.

2 hours ago

4

2 hours ago

4

English (US) ·

English (US) ·