ARTICLE AD BOX

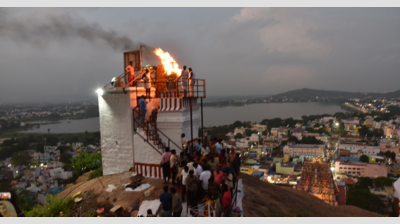

The lamp being lit at at Thiruparankundram hills. K Antony Xavier

K KannanThe recent controversy surrounding the lighting of the karthigai deepam atop Thiruparankundram hill reflects the complex intersection of faith, administrative discretion, inter-community sensitivities and constitutional responsibility.

Although the dispute on its surface relates to the specific question of where the deepam should be lit — whether at the deepathoon on the lower peak or at the long-established spot near the uchi pillaiyar mandapam — the deeper issue concerns how state and temple authorities must conduct themselves when long-standing traditions, community sentiments, and judicial oversight converge. The high court’s Dec 1 judgment provides a detailed historical narrative and legal reasoning that must form the basis of any mature reflection.

The Thiruparankundram hill is not merely a topographical formation but an ancient cultural-religious space. As the high court’s meticulous recounting of the major civil suits demonstrates — O S No. 4 of 1920, the subsequent appeals, and the final confirmation by the privy council —the ownership of the hill (except three small defined areas) was conclusively vested in the Subramania Swamy Devasthanam. The exceptions were only the Nellithope, the flight of steps leading to the mosque, and the precise summit area on which the mosque stands.

Therefore, the deepathoon, located on the lower of the two peaks, remains unambiguously temple property. The court notes that the deepathoon is neither structurally nor geographically part of the dargah and lies sufficiently distant from the mosque (≥50m). The pillar finds mention as established during Naickers’ rule, as per the inscriptions reported in the research publication (1984) of Prof Meyyappan of Annamalai University.

These findings remove the question from a territory-ownership dispute and place it squarely within the domain of temple administration and religious practice.Indian temple jurisprudence has consistently held that devotees are not strangers to matters of temple administration. Section 6(15) of the Tamil Nadu HR & CE Act recognises the right of “persons having interest” and the courts, including the Supreme Court in Bishwanath vs Thakur Radha Ballabhji, affirm that a worshipper may step in when temple authorities fail to act in the interest of the deity or the institution.In this light, the demand to light the deepam at the deepathoon is not merely a symbolic assertion; it is also, as the judgment stresses, an assertion of the temple’s title and its duty to protect unencroached areas, especially given the historical fragility of its territorial control.The 1996 judgment in W P No 18884 of 1994 allowed the devasthanam to choose a site anywhere on the hill, subject to distance restrictions from the dargah areas.

This implicitly acknowledged that the lamp’s location is an administrative, not a theological, choice and must be exercised with sensitivity to tradition.Given this discretion, it becomes incumbent on the HR & CE Board not to act in a manner contrary to the legitimate expectations of the devotees, especially when these expectations are rooted in Tamil cultural traditions of lighting lamps atop hills, the presence of an ancient stone deepathoon, carved for that purpose, and the need to preserve temple property through active assertion.If the authorities enjoy the liberty of determining the spot, that liberty must be exercised with both history and the wishes of the worshipping community.One of the most salient criticisms emerging from the present situation is that the state appears to have adopted a confrontational stance, often aligning itself with one narrative over another rather than fulfilling its constitutional role as a neutral facilitator of dialogue.The high court notes instances in which the administration appears to have taken sides, sometimes even more vigorously than the parties with a direct stake. In a matter involving two religious communities, the state must be scrupulously even-handed. The Indian constitutional model, with secularism as a national trait, does not demand the abnegation of religion; instead, it calls for principled neutrality, ensuring harmony without suppressing legitimate religious expression.Treating the issue as adversarial litigation rather than a matter requiring inclusive consultation exacerbates tensions and casts the executive as a litigant rather than a reconciliatory presence.The Mediation Act, 2023, specifically includes community mediation, empowering the state to activate structured, neutral mechanisms when inter-group disputes threaten public tranquillity.The Thiruparankundram issue is a model case for such intervention for four reasons: It involves recurring friction between two religious communities; there is a long history of misunderstandings and competing claims; the matter requires the joint participation of HR & CE, Waqf representatives, local stakeholders, and devotees; and the desired outcome is coexistence, not the victory of one side.The judgment records earlier peace committee resolutions in which both groups reached consensual outcomes, including allowing deepam lighting beyond 15m from the dargah.This demonstrates that dialogue works and that the state should have invoked the statutory mediation framework rather than allowing the issue to escalate into a courtroom confrontation.While the high court’s ultimate decision is grounded in historical fact and legal authority, it is equally true that courts today increasingly use mediation in complex socio-religious disputes.

In this case, too, the court might have considered initiating court-annexed community mediation, especially because the dispute concerns future practice rather than denial of essential religious rights; there is no inability to compromise on fundamental doctrinal grounds, and the issue is administrative rather than theological.

A mediated consensus, state-facilitated but community-owned, would have deeper social legitimacy and sustainability than an order issued under Article 226.Deepam is a symbol of illumination. Ensuring that its lighting becomes a moment of unity rather than discord is a shared responsibility of the state, the temple, communities, and the judiciary.(The writer is a retired judge of the Punjab and Haryana high court)

12 hours ago

4

12 hours ago

4

English (US) ·

English (US) ·