ARTICLE AD BOX

Fossils reveal snakes once possessed functional legs, challenging the notion of a linear evolutionary path. The discovery of Najash rionegrina, a 90-million-year-old terrestrial snake with intact hindlimbs and pelvis, demonstrated that evolution experimented with multiple adaptations, with some snakes retaining legs long after others lost theirs.

For centuries, snakes have been symbols of change, growth, evolution, and adaptation, found across most landforms, be it in forests, swampy areas, rivers or deserts.From shedding skins to being a major part of mythical stories, only a few transformations are as fascinating as their real evolutionary story.While most of us imagine snakes as sleek, limbless slitherers, yet a peek into time tells a more complex tale. Long before jungles and deserts echoed with hiss and coil, snakes once crept on small but functional legs.

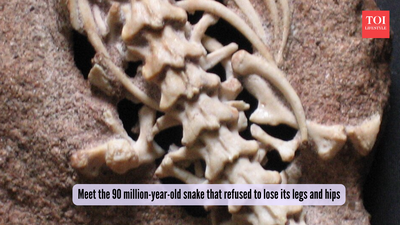

Meet the 90 million-year-old snake that refused to lose its legs and hips (Photo: Wikimedia Commons)

Evolution, far from being a straight path from lizard to snake, was full of detours and experiments. One such evolutionary rebel, a snake fossil discovered in the dusty rocks of Patagonia, rewrote what scientists knew about serpent origins.Popularly known as the ‘walking snake’, with its hips and hindlimbs still intact after millions of years, it is one of those examples which shows that nature is proof that it doesn’t always rush perfection, sometimes it also tests, and changes course slowly.

A fossil that changed snake science

Back in 2006, paleontologists Sebastián Apesteguía and Hussam Zaher dropped a major discovery in a Nature study with their discovery of a stunning fossil, of a 90-million-year-old early snake that still had a pelvis and solid hind legs.

When Najash rionegrina or the walking snake fossil was discovered in Argentina’s Candeleros Formation, herpetologists found a serpent with hips and legs still firmly attached to its body, not the limp remnants seen in modern snakes. This terrestrial fossil showed that some snakes moved across land with working legs long after others lost theirs, rewriting the idea that all snakes evolved in a single, straight evolutionary line.

Evolution didn’t strip snakes of their legs all at once. Genetic and fossil evidence all point towards a gradual fading, forelimbs disappearing first, while hindlimbs hung on for millions of years. In Najash’s case, those legs weren’t dead weight. They likely helped it burrow or brace itself while hunting.

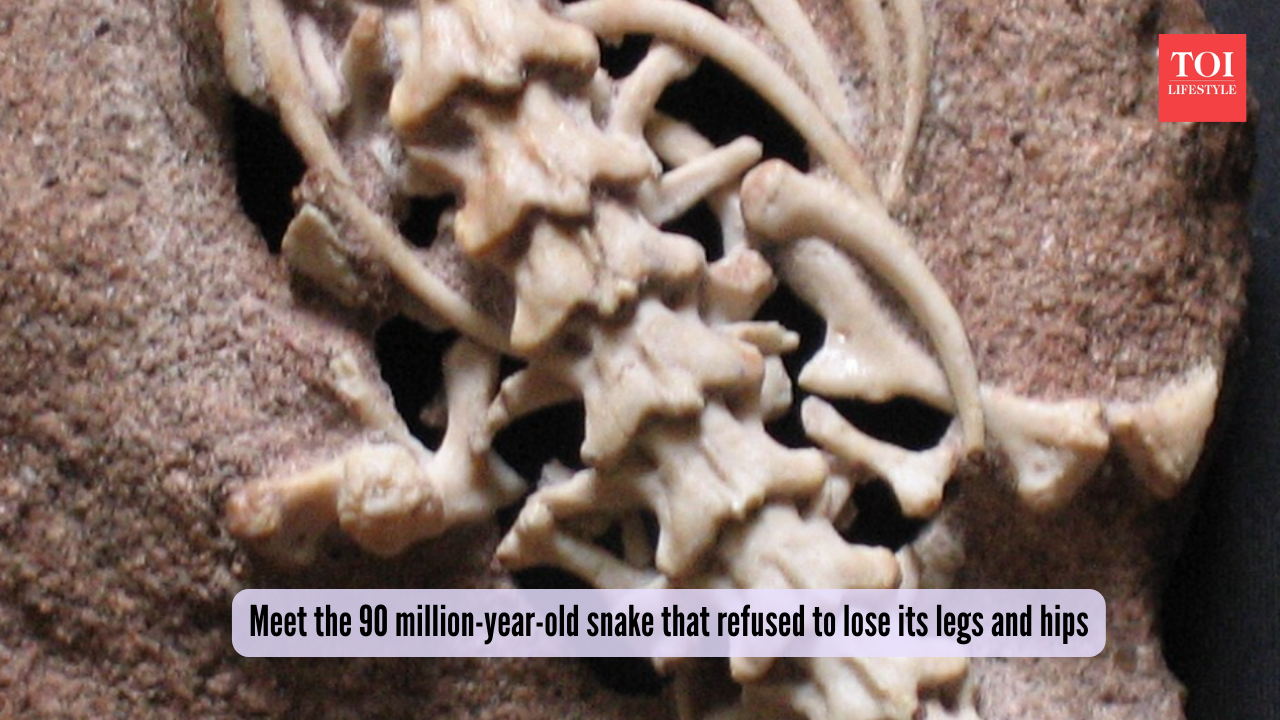

Snake with limbs intact (photo: New Scientist)

What made Najash special

Most ancient legged snakes were adapted to water, but Najash was a true land-dweller. Its skeleton shows a pelvis locked to the backbone, suggesting its legs were functional, not decorative.

CT scans of Najash skulls revealed both lizard-like and snake-like traits, painting a picture of evolution in motion. It wasn’t a transitional oddity, it was a living species that defied the emerging trend of limblessness for millions of years.

How scientists decoded its secrets

High-resolution scans exposed details long hidden in stone, and there were preserved pelvic bones and its mosaic skull structure. A cheekbone was also present, initially thought lost in snakes, forcing scientists to revise snake evolution models.

This information didn’t just redraw anatomical diagrams; it gave a new direction to paleontology, proving that fossils of even “known” creatures can surprise us when a new discovery comes in.

The bigger picture of evolution

Najash’s discovery redirects how we think about progress in evolution. Instead of a single route from lizard to snake, there were multiple paths, experiments, and environments guiding adaptation. Leg-bearing snakes weren’t evolutionary leftovers; they were successful in their own right.d layout suitable for a magazine or science blog format?

1 hour ago

3

1 hour ago

3

English (US) ·

English (US) ·