ARTICLE AD BOX

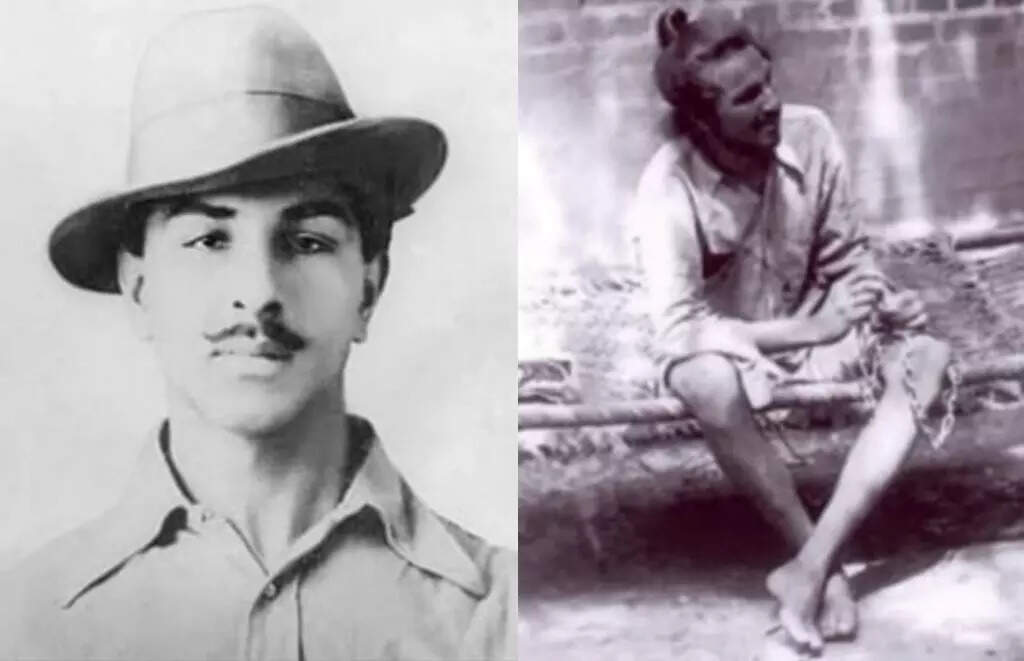

On the night of 22 March 1931, inside Lahore Central Jail, Bhagat Singh knew the end was near. The hanging was set for the next evening, but there was no trace of fear in his cell. He was calm, collected, almost meditative, reading Lenin, talking to his comrades Rajguru and Sukhdev, and discussing revolution until his final hours.

Yet, amid all this, one quiet request stood out. Scroll down to discover what he wanted for his last meal.

The request

According to historian Chaman Lal, one of India’s foremost researchers on Bhagat Singh and editor of The Bhagat Singh Reader, the revolutionary made a deeply symbolic final wish. He asked that his last meal be prepared by a Dalit prisoner named Bogha, who worked as a sweeper in the jail. Chaman Lal notes this episode in his writings and interviews (as cited in The Tribune, March 2021, and his book Understanding Bhagat Singh).

He explains that Bhagat Singh’s choice was a deliberate political gesture. By asking for food cooked by a man considered “untouchable” in the social order of that time, Bhagat Singh made his final act a statement against caste inequality, a social evil he believed was as destructive as colonialism itself.

Other historians, including Prof. Bipan Chandra and Shirley Tandon, have also highlighted that Bhagat Singh was deeply influenced by socialist and humanist thought.

In his prison writings, particularly his essay The Problem of Untouchability, he called caste discrimination “a disease eating into the vitals of Indian society.” His last request aligned perfectly with that conviction.

A revolutionary’s social vision

Bhagat Singh’s fight for freedom went far beyond the political goal of ending British rule. He imagined an India built on equality, reason, and dignity, not hierarchy. His reading list in prison reflected that vision: Marx, Lenin, Rousseau, and Indian reformers like Swami Vivekananda and Lala Lajpat Rai. Chaman Lal, in Bhagat Singh: The Jail Notebook and Other Writings, points out that Singh’s socialism wasn’t just about economics, it was about ending social divisions of caste and religion. For him, freedom meant liberation of thought as much as liberation of land. By requesting food from a Dalit prisoner, he was putting that belief into practice one last time. It was a message that the revolution he envisioned would be incomplete without dismantling caste.

The final hours

Prison records and eyewitness accounts, notably from jail officer Kishori Lal, cited later in A.G. Noorani’s The Trial of Bhagat Singh, describe the composure with which he faced death. On the evening of March 23, 1931, guards came earlier than scheduled, around 7 p.m., to carry out the hanging quietly to prevent unrest outside. When told his time had come, Bhagat Singh reportedly smiled and said that the time for the evening meal and for reading Lenin was not yet over.

He then calmly finished the book, set it aside, and walked to the gallows shouting Inquilab Zindabad. While it remains unclear whether his specific food request was fulfilled, given the hasty execution, the intent of that request survives in testimony and historical record. It is cited not as folklore, but as evidence of his unwavering social consciousness.

The meaning behind the meal

For Bhagat Singh, even a meal could carry meaning. His last wish was not about comfort, but conviction.

At a time when sharing food with someone of a lower caste could be seen as rebellion, he chose to make that act his final message. In doing so, he blurred the boundaries between political and social revolution. The gesture reaffirmed that equality wasn’t a slogan, it was to be lived, even on the eve of death.

What it means today

Nearly a century later, Bhagat Singh’s quiet choice remains a lesson in the moral depth of true revolution. His hunger for justice was larger than political freedom; it was for a society free of prejudice and hierarchy. His last request was never just about food, it was about breaking bread with humanity itself. Even as he faced the hangman’s noose, he was still teaching the country what freedom really meant.

1 hour ago

3

1 hour ago

3

English (US) ·

English (US) ·