ARTICLE AD BOX

A two-judge bench of Supreme Court on Jan 9 pointed to the repeated misuse of the Protection of Children from Sexual Offences (Pocso) Act - introduced in 2012 to shield minors from sexual abuse - saying it was increasingly being used to criminalise consensual teenage relationships or to settle personal scores.Hearing a matter related to an Allahabad high court order in a sexual assault case, justices Sanjay Karol and N Kotiswar Singh highlighted how a law designed to protect children can turn into a blunt instrument, threatening to harm those it was meant to safeguard while also eroding public faith in the justice system.The SC bench asked Centre to consider introducing a 'Romeo-Juliet' clause to exempt "genuine adolescent relationships" from Pocso's harshest provisions.

The court called for a legal carve-out for consensual close-in-age relationships and action against those who misuse the law to "settle scores".

At the same time, the bench was careful that the moral and legal force of Pocso Act be kept intact. It said the Act was "the most solemn articulations of justice aimed at protecting the children of today and the leaders of tomorrow", underlining that the problem lay not with the law's intent but in how it was being applied on the ground.

The top court's apprehensions are well-founded, with experts pointing to lasting impacts caused by the misapplication of the law."In one case we worked with, a 17-year-old boy and a 16-year-old girl were in a consensual relationship. While the boy's family opposed it, the girl's family eventually accepted the couple. Due to mandatory reporting, the boy spent several months in an observation home. After his release, the couple went on to live together with the girl's family and are now raising a two-year-old child.

However, the impact of the case continues - their son is still struggling to get school admission due to complications in documentation," said Sachi Maniar, director of Mumbai-based Ashiyana Foundation, which works with children in the juvenile justice system."Many cases under Pocso Act involve consensual adolescent relationships. Despite this, it is usually the boys who are sent to observation homes. Many ask, 'Is it wrong to fall in love?', 'Why am I being punished?' and carry a deep sense of betrayal, injustice, and trauma from being institutionalised.

Some even say they will never trust relationships again or feel they must avoid girls altogether," adds Maniar.The bench went beyond procedural law to address what it described as a deeper crisis around the misuse of Pocso. Quoting earlier judgments, it warned that when a law of "noble" intent is twisted into a tool of vendetta, "the notion of justice itself teeters on the edge of inversion".The court pointed to two sharply unequal realities. On one side are children who are silenced by fear, stigma or poverty, making justice distant and uncertain.

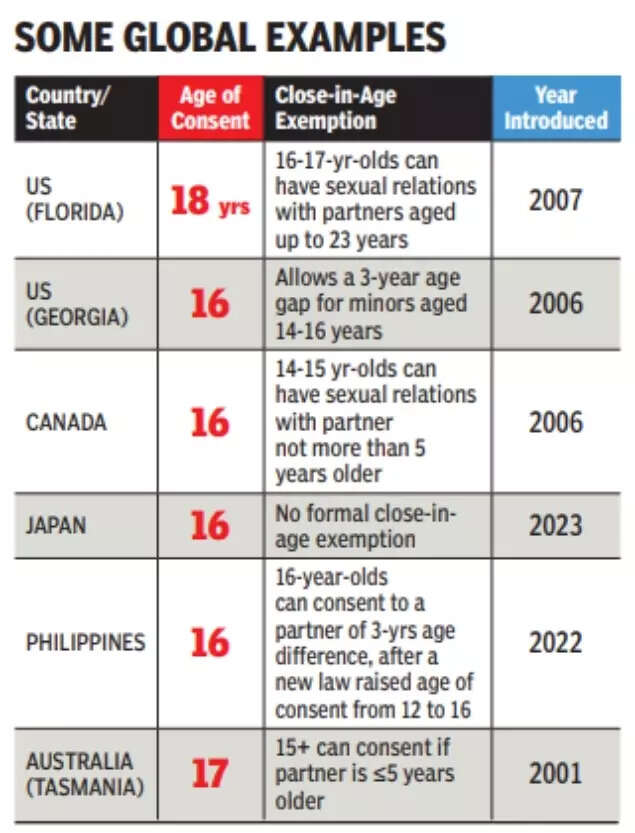

On the other are those "equipped with privilege, literacy, social and monetary capital", who can manipulate the law to their advantage. It is this imbalance that has led to consensual adolescent relationships being reframed as criminal offences with family or social disputes getting dragged into court.The judges also reminded lawyers of their ethical duty to act as gatekeepers against frivolous or vindictive litigation, warning that unchecked misuse of powerful criminal laws corrodes public confidence in justice.The 'Romeo-Juliet' clause proposed by Supreme Court is not a new or radical idea. Many countries have brought in close-in-age exemptions to prevent teenagers in consensual relationships from being prosecuted under statutory rape laws simply because one partner is technically a minor.In the US, for instance, at least 43 states have some form of such protection, effectively decriminalising sex between teenagers of a similar age.

Canada allows sexual relations between 14- and 15-year-olds and a partner that's older by no more than five years, with a tighter two-year exemption for 12- and 13-year-olds. These provisions are designed to recognise adolescent relationships without opening the door to exploitation.Typically, such laws protect the older partner from arrest if the age difference is within a defined limit and the relationship is consensual.

Non-consensual acts remain fully criminal, ensuring that predators cannot hide behind the exemption.However, experts warn that age gaps alone cannot capture the complexity of adolescent consent. As research has noted, focusing only on age "may mask realities of how informed an adolescent's consent truly was", making it essential that a minor's testimony and the surrounding circumstances remain central to any legal assessment.Recent reforms, such as in the Philippines, show a global trend towards raising the age of consent while still recognising the reality of teenage relationships.By calling for a Romeo-Juliet clause, Supreme Court is signalling that India's child protection framework needs a more nuanced middle ground - one that distinguishes between abuse and adolescent intimacy, and between predation and peer relationships.If Parliament acts on the court's suggestion, it could prevent thousands of young couples from being dragged into the criminal justice system, while also freeing police and courts to focus on genuine cases of sexual violence against children. At the same time, safeguards would be needed to ensure that such an exemption is not misused to shield coercion or exploitation. For a law as powerful and sensitive as Pocso, Supreme Court's message is clear - protect children fiercely, but do not let the law become a weapon against them.But Anant Kumar Asthana, an advocate who practices child justice and criminal law in Delhi, argues that a Romeo-Juliet clause may not be a ready solution."The idea of introducing close-in-age exception (Romeo-Juliet clause) in Pocso regime does not fundamentally advance the cause of decriminalisation of consensual or genuine adolescent sexual relations. Instead, it binds judges to one more rigid and mandatory formula that can only be applied in a regulated manner and in a specific set of facts and figures," he said."In a law like Pocso, the chasm between access and abuse can be best navigated in a just and compassionate manner by a trial judiciary that is empowered with widest possible judicial discretion in matters of arrest, bail, trial and sentencing," he added. "Invoking Romeo-Juliet exception can be one of the options that can be legislatively or judicially made available to Pocso judges, but it becomes a problem when this option is put as the only option for exercising judicial discretion.

"Text and inputs: Rajesh Sharma, Ambika Pandit

1 hour ago

4

1 hour ago

4

English (US) ·

English (US) ·