ARTICLE AD BOX

It’s been a long few days in the world of chess. The issue of cheating in the sport is back in the headlines with a former world champion accusing another grandmaster of being up to no good. Courts have been dragged in to adjudicate with one player suing the other for slander. Only, this time around, there’s a twist: unlike the Magnus Carlsen vs Hans Niemann incident, where Niemann sued the former world champion for implying that he had cheated, this time around it’s former world champion Vladimir Kramnik who is doing both, the accusing and the suing, after dragging grandmaster David Navara to court.

This is the latest step taken by Kramnik in his infamous crusade to weed out cheating in online chess, a fight that the Russian seems to have dedicated significant mindspace to over the last couple of years. Kramnik posts data on his X account implying that there was something fishy in the way many grandmasters were competing in online games. It’s a fight that has gained Kramnik no admirers, at least not publicly.

The most recent grandmaster to try and coax Kramnik to see the light of reason is Levon Aronian, who’s now posted three long emotion-laced posts on X aimed at a man who he calls his “chess parent”, each post displaying the delicate tact a hostage negotiator would ideally employ.

“Volodya, my friend,” Aronian exhorts in one of his posts on X aimed at Kramnik using the Slavic name for Vladimir. “Perhaps my letter will seem disrespectful and inappropriate to you. But my goal is one. Let’s reduce the intensity of passions… You think you’re saving chess from cheaters. But most of us see you as the guy with the hammer who thinks everything is a nail,” Aronian says at one point.

Over the course of his three posts, Aronian tries multiple tacts. Telling Kramnik that he’s a great champion and amateurs do not deserve the attention he’s given them in his YouTube breakdowns (“the king of beasts is engaged in catching mice”). Trying to convince Kramnik how much the world would benefit from an analysis of his own tactics from his world championship duels instead. Reminding the Russian how he was himself bullied by Veselin Topalov and his team, who accused Kramnik of being up to no good because he visited the toilet too many times (an incident known popularly as Toiletgate) during their World Championship battle in 2006. Trying to reason with him by saying that the sport is a family and kin cannot go around suing each other. And finally, telling him that no one who’s close to him in the sport thinks what Kramnik is doing is “good and pure”.

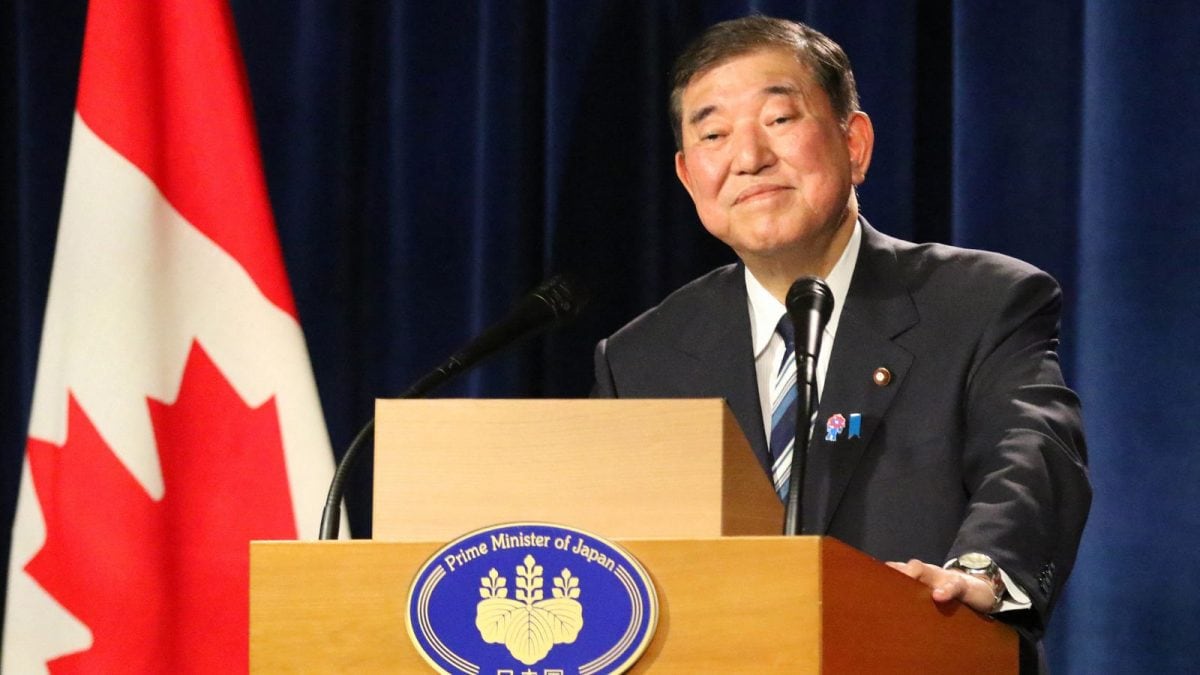

Former world champion Vladimir Kramnik in conversation with Chess24’s Mike Klein during round 9 of the Chess Olympiad in Budapest. (FIDE)

Former world champion Vladimir Kramnik in conversation with Chess24’s Mike Klein during round 9 of the Chess Olympiad in Budapest. (FIDE)

“Chess world does not appreciate you enough… I feel the chess world and the new generation need to know about you… about who you are,” Aronian writes at one point. “And I want you to remember it as well.”

There, Aronian praises the Russian for being the “biggest revolutionary when it comes to chess… who challenged every single dogma” in the sport.

Story continues below this ad

That’s precisely how chess fans of a certain vintage will remember the Russian. As the man who resuscitated the abandoned Berlin Defence at the 2000 World Championship to nullify the attack of Kasparov so completely that the reigning world champion, with a voracious appetite for bulldozing through defences, ended with zero wins. He was the immovable object in front of Kasparov’s unstoppable force of an attack. He could fluster Kasparov, the most intimidating man in the sport.

Built differently

Kramnik was built differently. When he first emerged on the global stage at the Manila Olympiad in 1992 rocking long hair, spectacles, a tucked in short-sleeved shirt, the tall Kramnik looked like a rockstar cosplaying as a laboratory assistant. If Kasparov, his predecessor on the world champion’s throne, vroomed to a game in a Mercedes, Kramnik probably took the bus. He was always outspoken and an independent thinker, even if it meant rubbing people the wrong way. He was never quite taken in by the trappings that come along with being world champion. Like fame or money. What the world thought about him was also never a concern.

Vladimir Kramnik during his younger days. (PHOTO: Kramnik via X)

Vladimir Kramnik during his younger days. (PHOTO: Kramnik via X)

“For me, what I think of myself is more important than what society thinks. That may sound arrogant, but I have my own views and don’t care about the views of the public,” Kramnik told the editor of New In Chess magazine before he squared off against Kasparov in 2000. “My approach to chess is different. For most other chess players, chess is purely a sport, for me, it’s more of a scientific activity.”

It’s this ability to stay unmoved by the world’s perception of him that helped him retain his title against Topalov when the Bulgarian and his entourage tried to raise questions about his own integrity in the Toiletgate scandal.

It’s also what’s helping him stay on course with his current allegations of cheating in chess despite the rest of the world disagreeing with him.

Story continues below this ad

Before Topalov in 2006, it was the 2000 world championship battle against Kasparov that established Kramnik’s place in history. Not just as Kasparov’s nemesis or his antithesis. He was Kasparov’s kryptonite, a man who would beat the Russian legend, who was actually his mentor at the Botvinnik-Kasparov School, and then shrug it off as no big deal. Unlike others, beating Kasparov was not an achievement for him.

“It has always surprised me when people get so hung up about a victory over Kasparov,” he once told New in Chess when he was just 21, not even a world champion. “Then it seems as if it happened by accident. I don’t believe I defeated Kasparov by accident. The idea that Kasparov is so exceptional is a myth created by journalists.”

In the same interview, Kramnik proceeded to go on multiple tirades. There was one rant about chess becoming too commercial. Then, another rant about how the chess players of his generation were playing “substandard” chess. At some point he says that he wasn’t a good player, but other players were even worse. Now compare those comments to the ones he made about Gukesh and Ding Liren during last year’s world championship, where he excoriated both players for their level of chess. Those criticisms earned him the wrath of the two most populous nations of the world. But for Kramnik, he was probably just measuring both players by the standards he set for himself in his playing days.

A few years after that interview about chess becoming too commercial, he finds himself facing Kasparov in that 2000 World Championship where the prize fund is an eye-watering $2 million. A 24-year-old Kramnik responds to that by declaring that he would have played for free.

Story continues below this ad

At another point in his career, when he played Peter Leko in 2004 for the title, Kramnik came under some criticism for playing out short draws. In an interview, it was put to him that the fans would have wanted to see more chess. It was then that he memorably exclaimed: “A painter never asks people what they want to see. He just paints.”

Even with his chess, as with his opinions and convictions, Kramnik was not playing to the gallery. He was playing chess as he deemed fit. The world may criticise him as a man with a hammer hell-bent on hitting every nail on its head. But there can be no reduction in the intensity of his passions.

.png)

.png)

.png)

English (US) ·

English (US) ·