ARTICLE AD BOX

On a sun-drenched July afternoon, the beat of wedding drums echoed across the hills of Shillai, a remote Himalayan village in the Trans-Giri belt of Himachal Pradesh’s Sirmaur district. As villagers danced the pahari nati and showered flower petals, the bride, Sunita Chauhan, participated in the traditional wedding rituals. But what set the wedding apart was the presence of not one, but two grooms.

The wedding, which has since gone viral and sparked curiosity and debate beyond the state borders, is neither scandalous nor new to the region. It is a remnant of the fading ancient practice known colloquially as Jodidara or Jajda, a form of polyandry in which one woman marries brothers. Though the tradition now survives discreetly among members of the Hatti community, the custom was common across the rugged, agrarian region until a few decades ago.

“Twenty-five years ago, it was not unusual,” says Harshwardhan Chauhan, Himachal Pradesh’s Industries, Labour, and Parliamentary Affairs Minister and the MLA for Shillai. “But in the past decade, I would estimate fewer than 50 such weddings have taken place.”

For outsiders, such marriages may evoke a sense of otherness and raise questions about gender, autonomy, and modernity. But in Shillai (Sirmour) and other tribal areas of Himachal Pradesh, including Kinnaur and Lahaul-Spiti, polyandry is tied to land, legacy, and survival.

The Hatti community — which got its name as they traditionally sold agrarian goods in marketplaces called hatts — spans about 450 villages across the Trans-Giri region of Himachal Pradesh and bordering areas of Uttarakhand. These tightly-knit agricultural communities once relied on collective labour to make ends meet.

For centuries, the region’s geography, steep slopes, fragmented terraced fields, and sparse infrastructure dictated a kind of economic and familial pragmatism. In this context, polyandry served a specific and functional purpose: preserving undivided ancestral land and fostering cooperation in joint families.

Sitaram Sharma, chairperson, a public school in Shillai, remembers growing up in a joint household where his father and grandfather practiced Jajda. “Only about five percent of families still follow it,” he says. “Up until around 50 years, both polyandry and polygamy were practiced in the community. Families had no land, there were no jobs, and survival depended on staying together.”

Story continues below this ad

Families often had only a bigha or two of cultivable land — barely enough for one household, let alone many. To divide it further, Sharma says, would have been catastrophic. “If four brothers married four wives, their children would split the land again and again. Jajda ensured land stayed whole, and families stayed together.”

His reflections are echoed by the first chief minister of Himachal Pradesh YS Parmar, who, in his 1975 ethnographic study Polyandry in the Himalayas, wrote, “The real reason for the existence of polyandry is economic. It is the best system suited to the conditions of the people where division of land is not possible and joint cultivation is advantageous.”

Beyond economics, the practice wove an emotional lattice among siblings. “Fraternal polyandry binds brothers together. It discourages fission in the household and promotes unity, since the brothers have a common wife, common children, and shared responsibilities,” says Sharma.

It was also, in many ways, a form of population control. “It regulated reproduction naturally. By limiting the number of wives in a family, it also limited the number of children, thereby conserving resources,” Parmar added.

Story continues below this ad

Mythology and modernity

For many locals, especially among the older generation, the practice is sanctified by religious mythology. In the Mahabharata, Draupadi — wife to the Pandavas — is considered the first Jajda bride. “People say, if such great men could live like this, why not us?” says Sharma.

Parmar writes of it too: “The custom has its sanction in mythology and legend. The people of the

region continue to follow the example of these legendary heroes.”

But today, such explanations are met with discomfort, or outright silence. A 2025 study by sociologists Shiv Kumar and Thakur Prem Kumar, published in the peer-reviewed Journal of Neonatal Surgery, attributes the decline to education and employment. “Youngsters are hesitant,” Sharma says. “They work in cities, some go abroad. They are scared of being mocked.”

“Earlier, people had no choice. Now people are stepping out, getting educated, watching the world through screens and books. The joint family is giving way to nuclear,” he adds.

Story continues below this ad

However, Shravan Kumar, 42, an assistant professor from Lahaul-Spiti, argues that such marriages are neither regressive or coercive. “Couples in these relationships are not forced into anything,” he says. “They live lives with perfect autonomy, not unlike traditional two-partner marriages. If the three partners do not get along, the bride or one, or both, of the grooms can initiate divorce through a simple ceremony that translates to ‘breaking the thread.’”

Customary kinship across the Himalayas

Though increasingly rare, polyandry remains prevalent across several Himalayan communities, including certain high-altitude pockets of Nepal and Tibet. Palki Tsering, a 37-year-old researcher from Kinnaur and general secretary of the Lahaul-Spiti Bodh Sangh, a local organisation focused on the welfare of the Buddhist community in the Kinnaur and Lahaul-Spiti regions, notes, “Both polygamy and polyandry are indeed practiced among the Hatti community and in tribal regions of Kinnaur and Lahaul-Spiti. Though the practice has declined over the years, it now tends to be more consent-based rather than arranged.”

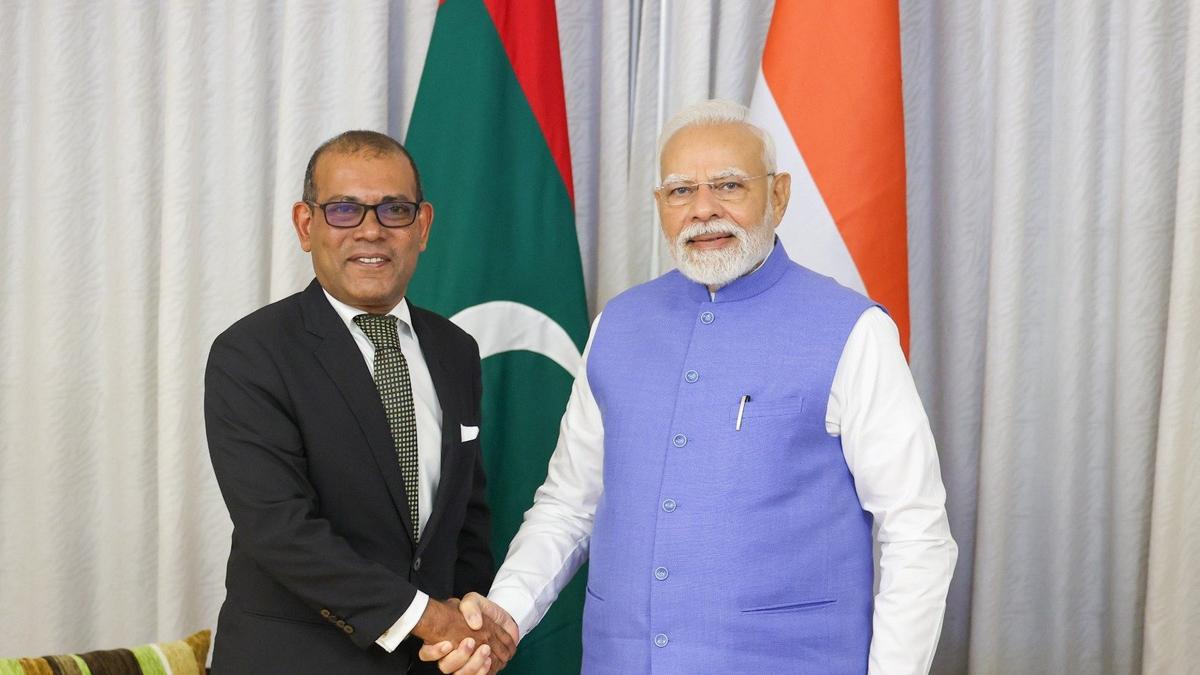

Bride Sunita Chauhan with grooms Pradeep and Kapil Negi(PTI)

Bride Sunita Chauhan with grooms Pradeep and Kapil Negi(PTI)

Case in point: Sunita Chauhan, the bride, was quoted by news reports as saying: “I was aware of the tradition and made my decision without any pressure. I respect the bond we have formed.”

In her case, one husband, Pradeep from Shillai village, works in a government department, while the other, Kapil, is employed abroad. Tsering says the tradition originally served a practical purpose: “In the rugged terrains of Kinnaur and Lahaul-Spiti, consolidating property and land was essential. One son would typically work outside the village to earn a living, while the other stayed back to manage the household and community affairs.”

Story continues below this ad

Even today, the economic rationale persists. Maintaining multiple households is financially burdensome, especially with the added cost of raising children. As Tsering explains, “If brothers marry different women, they are treated as separate households and must each contribute separately to the village community. A household of three brothers with one wife is considered one household and will thus only contribute once.”

Sushil Brongpa of Lahaul-Spiti, former Rajya Sabha MP, recalls encountering a study on his family at Patiala University in 1971. The book, A Study of Polyandry by Prince Peter of Greece and Denmark, was published by Cambridge University Press. Brongpa shared, “My uncle and father had a common wife, and I, too, share a wife with my uncle’s son. The system ensured that both land and the family stayed together.”

Wedding rituals in these regions also diverge notably from typical North Indian customs. Rather than a groom arriving with a baraat, the entire village often visits the grooms’ house. The ceremony includes offerings of jaggery and invocation of the Kul Devta (family deity). A unique ritual called Seenj is performed at the groom’s residence.

Brongpa recalls simpler forms of marriage in earlier times: “With limited resources, ‘gandharv’ weddings — unions without elaborate rituals — were common. Sometimes, the elder brother and his friends would simply bring the bride home. In some cases, a bottle of liquor sufficed as a symbolic shagun, or a small advance would be given as a token for the woman’s security.”

Story continues below this ad

Legality of polyandry

Under Indian law, polyandry is not legally recognised. The Hindu Marriage Act, 1955 and the Special Marriage Act require monogamy, that is, neither party may have a living spouse at the time of marriage. Section 82 of the Bharatiya Nyaya Sanhita (BNS) criminalises bigamy with up to seven years’ imprisonment. If the prior marriage was concealed from the new spouse, the imprisonment can extend to 10 years.

However, these laws do not automatically apply to members of Scheduled Tribes (STs) unless extended by the central government. This legal loophole allows for customary practices, like Jodidara, to survive in tribal regions. Under Section 13 of the Indian Evidence Act, 1872, a longstanding custom can be admitted in court as a legal right. Courts have repeatedly upheld this principle, especially when it concerns family law in tribal communities.

The Hatti community in Sirmaur shares deep-rooted kinship ties and cultural practices with Jaunsar-Bawar — an area that was historically part of the princely state of Sirmaur before its incorporation into modern-day Uttarakhand. Today, the Tons River serves as both a geographic and policy boundary: while the Jaunsari Hatti on the Uttarakhand side are recognised as a Scheduled Tribe, their counterparts in Himachal continue to await similar protections. Though Parliament passed a bill to grant them ST status in 2022, the Himachal Pradesh High Court stayed its implementation in January 2024, citing “manifest arbitrariness” in the classification process. The case is currently sub judice.

Both Harshwardhan and former Deputy Advocate General Himachal Pradesh Chander Mohan Thakur note that despite lack of formal recognition to the Hatti community in Himachal Pradesh several court cases involving the Hatti community in Himachal have been settled under customary law, specifically the Jodidara system.

Story continues below this ad

Thakur cites the Lokur Committee Report (1965), according to which the first official criteria for identifying a Scheduled Tribe was: “primitive traits, distinctive culture, geographical isolation, shyness of contact, and backwardness.”

“Any custom that contradicts public policy can be struck down. But when it comes to tribal communities, their custom prevails over general law,” says Thakur.

MLA Harshwardhan agrees: “There are several tribal traits in the Trans-Giri region, and that includes polyandry. Customary law takes precedence in such cases. Several disputes have been resolved under these customs.”

Revenue officers, too, often encounter the system in land records. “When a new official comes in,” Sharma says, “we have to explain how Jodidara works — one wife, at least two fraternal husbands, one household.”

.png)

.png)

.png)

English (US) ·

English (US) ·