ARTICLE AD BOX

Tamil Nadu is the graveyard of national political parties. It buried the Congress at its peak then in 1967. The BJP, also at its peak now, has been pregnant with possibilities but has failed to deliver. Never a serious player in the state before the dawn of the Modi-era, the BJP has been humbled in every election since his arrival in 2014 (2019, 2021 and 2024).

Pundits and laypersons, Tamil Nadu confounds everybody alike. What makes it the strongest citadel of regionalism in contemporary politics that is now soaked in nationalism? Why is it a unique entity even among its culturally similar southern states? All these states are also fiercely proud of their cultural moorings, but none practices antagonism to national parties as a principle of state policy, so to say. What makes it stand out and stand apart? Is it true that a monolithic national narrative suppresses or seeks to suppress the state's distinct Tamilakam (Tamil Nadu of yore) identity and ancient glory? Or, do the state's Dravidian parties deliberately stoke the sense of cultivated alienation and grievance to perpetuate their careers? What has Dravidian politics delivered that the state does not want a taste of any other model? What is the collective angst of the Tamils? Is it justified? Why can't the rest of India fathom it? As another grand electoral spectacle looms in 2026, these are some of the myriad questions that need to be addressed. Not to predict winners and losers, but just to understand why Tamil Nadu is the way it is.

In this new series, that is what Chennai-based senior journalist, TR Jawahar, will attempt to do. He will dig deep into history and heritage, arts and archaeology, language and literature, cinema and culture, kingdoms and conquests, castes and communities, religion and race and, of course, politics and pelf, to paint a picture of the state that might help you understand whatever happens when it happens.

Read More

The alarm now goes off, and it is Time to wake up and ride the turbulent Tide: a transition from the profound poetry of Tamil Bhakti to the pungent theatre of Dravidian politics.

As we have unpacked before, Bishop Robert Caldwell—that linguistic wizard with missionary mischief baked into his chalice—authoritatively severed the Dravidian languages from Sanskrit’s ancient 'grip' (see parts 8 & 9). His 1856 and 1875 tomes were not merely academic exercises; they were linguistic landmines. By providing a scholarly basis for the independence of the Southern tongues, he ignited a wave of regional pride and set the stage for deeper divides, turning words into weapons against perceived Aryan overreach.

Caldwell’s work, a sophisticated blend of evangelism and etymology, argued that Dravidian tongues were ancient and independent. This revelation was a double-edged sword: while it fueled a new Southern identity, it simultaneously sowed seeds of suspicion toward Northern Sanskrit dominance. It was a clever cut that cut both ways, separating the linguistic family tree just as the colonial administration was looking for new ways to categorize and control its subjects.

Brahmin Bias: The Provocation in Posts and Pay

The seeds of this schism took root in the 19th-century colonial cauldron of the Madras Presidency, where British rule amplified long, latent tensions. A staggering disproportion emerged: Brahmins, a mere 3 percent of the population, snagged nearly 70 percent of the administrative and educational posts. Their Sanskrit savvy and English adaptability transformed them into the ultimate gatekeepers of opportunity.

Furthermore, Brahmins, with their profound knowledge of scriptures, became the primary consultants for the swarm of Indologists who descended upon the Indian mindscape. Not all of these seekers arrived with honourable intent; many were looking for a hierarchy to exploit, and they found a ready-made skewed social structure here.

The bias was even visible on the payroll. At Madras University, it is recorded that a Sanskrit teacher out-earned a Tamil counterpart—a case of a Sanskrit-ified salary that left native tongues in the dust. This wasn't just a matter of dry statistics; it was a punch to non-Brahmin pride, breeding a resentment that echoed the caste critiques of North India but with a distinct, Southern linguistic twist.

While Raja Rammohan Roy was pushing social reforms up North, the South was simmering with "job jealousy". This provocation transformed the term Paarppan—a sly jab at Brahmin 'seers'—into a household hiss. British census data from the 1870s and subsequent reports from the 1912 Public Service Commission revealed the depth of the divide: Brahmins held nearly half of all high-ranking native roles, a statistic that non-Brahmin pamphleteers wielded as proof of an Aryan Aristocracy.

Today, this same undertone fuels Tamil Nadu's quota battles, where OBC and Dalit demands clash with merit and math in NEET rows and court caps—a lone furrow that the Justice Party first ploughed against the national grain of unified reform.

Whispers from Journals: Early Non-Brahmin Grouses

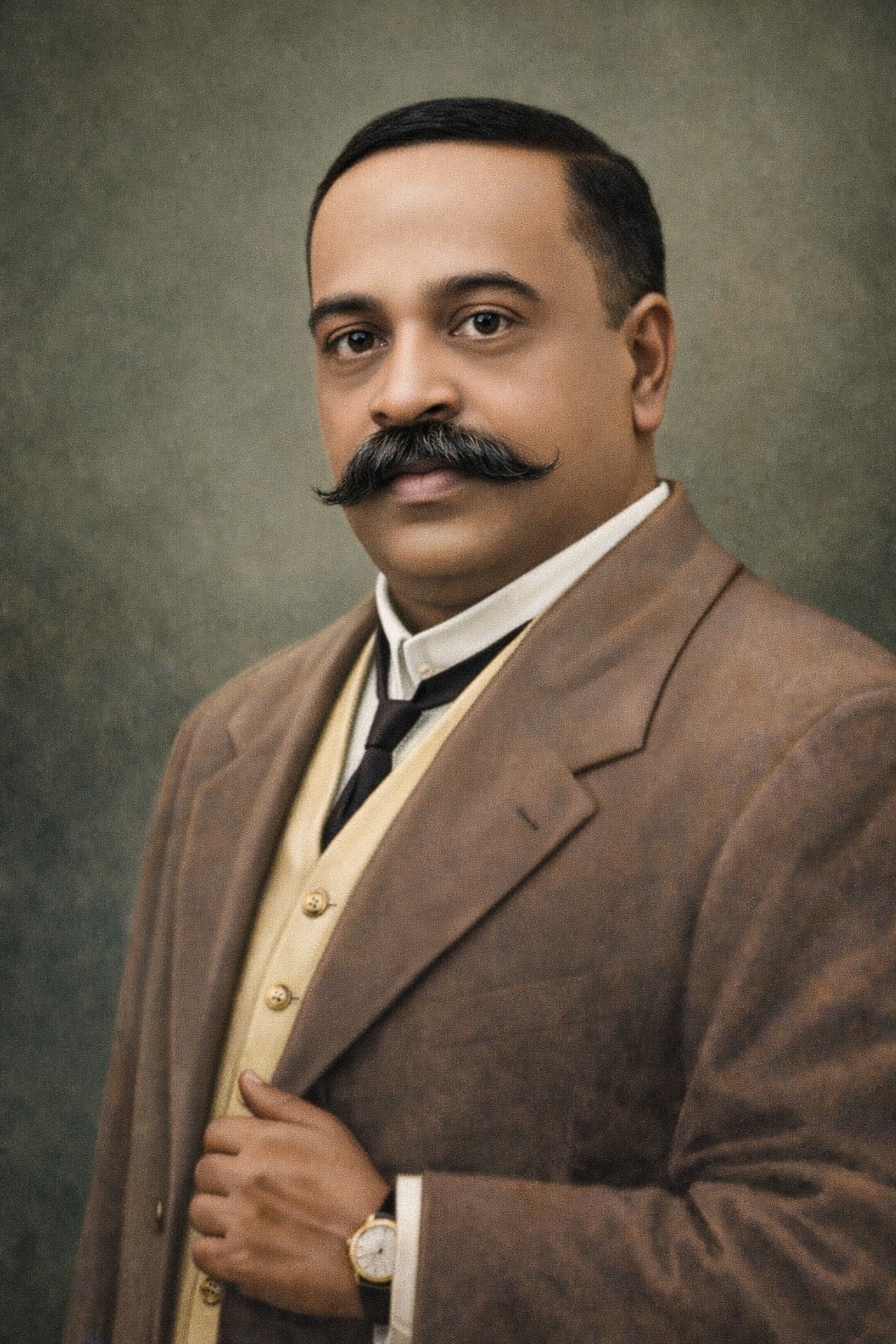

C. Iyothee Thass was a Dalit-Buddhist pioneer who rejected "Aryan" myths of superiority and championed the "original Dravidians."

By the late 19th century, these grumblings found a megaphone in journals like Dravida Mitran, a mouthpiece for non-Brahmin woes. Figures like C. Iyothee Thass, the Dalit-Buddhist pioneer, began wielding the Aryan-Dravidian gulf as a cultural cudgel. Thass was a radical visionary who rejected "Aryan" myths of superiority and advocated for the "original Dravidians".

In 1891, his writings lit early fires: "The Brahmin is the Aryan invader who enslaved us," he asserted, a quote that predated the organized Dravidian movement by decades. Thass’s Sakya Buddhist Society and his weekly Oru Paisa Tamizhan (One Paisa Tamilian) were the social scalpels of their day, slicing through Hindu hierarchies to expose the nerves of exploitation.

Of relevance is Tamil Nadu Chief Minister M K Stalin’s declaration on January 25 that the ‘2026 poll is an Aryan – Dravidian battle’. The ghost refuses to go away.

Meanwhile, the Pure Tamil Movement gained steam, de-Sanskritization literature and de-Hinduising identities—a willy-nilly fallout that deepened North-South rifts. While the North was occupied with Swadeshi boycotts of British goods, the South’s target was the Brahmin monopoly. This seeded a political rupture that lingers in today's federal fistfights over Hindi imposition and cultural dominance.

An interesting nugget here: Thass’s 1886 petition to the Governor for a "Dravidian" census category was ignored, yet it perfectly prefigured the Justice Party’s eventual quota push—a subtle shift against the national drift of pan-Indian unity.

Nair's Fire: The Justice Newspaper and Overseas Odyssey

Dr. T.M. Nair framed “Brahmin invasions” as a rallying cry for Tamil, caste, and cultural assertion.

Enter Dr. T.M. Nair, the Malayali physician-turned-journalist whose 1915 launch of the Justice newspaper lit the fuse. Nair's editorials riled against "Brahmin invasions," weaponizing the rift into a multifaceted instrument: a political hammer against the Northern-dominated Congress, a linguistic lance for Tamil pride, a social scalpel for caste cracks, and a cultural cudgel against Sanskrit supremacy.

Nair’s jaunts to London were commendable, yet they often felt like comic cameos in the grand theatre of colonial lobbying. He embarked on a "South Indian Safari through Whitehall", preaching Dravidian dignity to puzzled Lords and rallying support for non-Brahmin quotas. "We seek justice from the empire's heart," Nair declared. Lesser known is his bold bid at the 1919 Paris Peace Conference, where he lobbied for Madras representation—the effort was snubbed but it highlighted the South’s early international outreach despite Delhi’s shadow.

But here was the boomerang: while Nair globe-trotted for reform, back home, his highbrow, elite style alienated the masses. It was a classic contradiction that foreshadowed the party's eventual pitfalls. Connect this to the North’s Lokmanya Tilak, whose mass rallies unified Hindus of all stripes; Nair's elite appeals kept the South fractured.

Founding Frenzy: A Trio of Titans and Besant's Bane

The frenzy peaked on November 20, 1916, with the birth of the South Indian Liberal Federation (SILF)—quickly dubbed the Justice Party after Nair's paper. The founding trio was a powerful, if eclectic, combination.

Dr. T.M. Nair, the fiery Malayali anti-Congress crusader; P Pitti Theagaraya Chetty, the Telugu tycoon whose philanthropy was a quiet act of affirmative action long before quotas. His 1897 Theagaraya College provided the "bricks and mortar" for non-Brahmin advancement; and C Natesa Mudaliar, the Tamil Vellala organiser whose grassroots broadcasting of the message earned him the title "Doyen of the Dravidian Movement".

Their Non-Brahmin Manifesto, released in December 1916, was punchy and precise. It called for communal reservations to break the Brahmin stranglehold and guarded linguistic turf with anti-Hindi hints. "We hold the scales even between castes," it proclaimed, setting a separate path against the rising national swell of Gandhi’s Non-Cooperation.

Yet, the highbrow image stuck—it remained a "silk-sari soiree" of doctors, lawyers, and zamindars. Their velvet-rope vibe often excluded Dalits, tribals, and Muslims, diluting their broad appeal. Internal chasms emerged and enlarged early: moderates like Theagaraya favoured petitions, while radicals like Nair pushed for defiance.

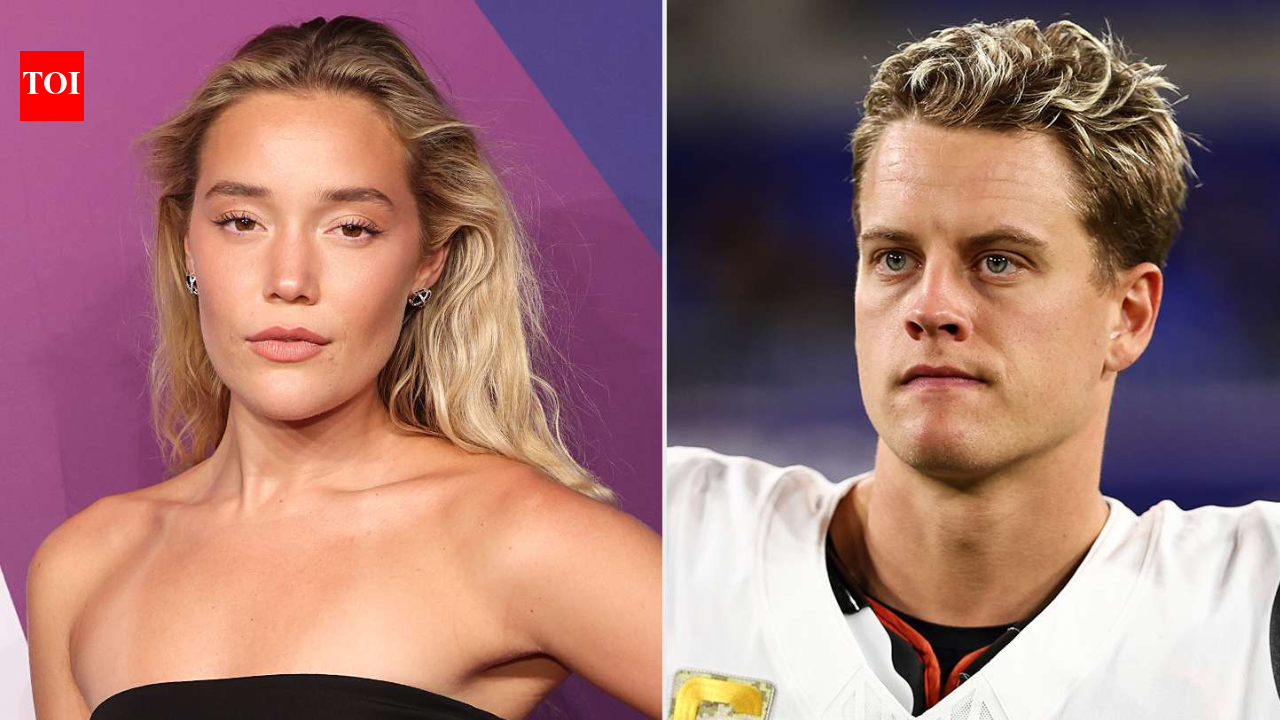

Annie Besant, the Irish Theosophist, was criticised by the Justice Party as promoting Brahmin interests (Photo: Getty Images)

The most-hated "memsahib" of the movement was Annie Besant. The Irish interloper, with her Theosophical ties and Home Rule League, was seen by the Justicites as "Brahmin boosterism in disguise". Nair’s acid tongue turned her Congress coziness into a searing standoff. A spicy, lesser-known detail: Nair won a 1913 defamation case against Besant over the scandalous "initiating rites", (sexual misconduct with young boys), claims involving C.W. Leadbeater. This Theosophical takedown was a personal victory that Nair used to embarrass her political Home Rule push.

While Gandhi’s satyagraha stirred the Northern masses, the Justice Party opted for polite pleas to the British—a persistent undertone of the South’s perceived isolation from the general freedom fervour.

Ideology's Edge: Schisms as Strategic Swords

At its core, the Justice Party wielded the Aryan-Dravidian estrangement as a strategic sword. This wasn't mere rhetoric; it was a weapon that carved space for non-Brahmins in a Raj rigged against them. It was political to defy Northern dominance, linguistic to champion Dravidian (not necessarily Tamil!) purity over Sanskrit, and social to dismantle caste monopolies.

But the contradictions were glaring. Their pro-British pragmatism bought them limited leverage but cost them their anti-colonial soul. They were a "loyal opposition" that often seemed to oppose Brahmins more than the Empire itself. Nair’s death in 1919, amid simmering ego clashes, hinted at the internal infernos to come. The party’s elite exclusion—high-caste Hindus dominating while leaving minorities on the margins—sparked a diluted electoral vibe even in their prime.

The disconnect from the freedom struggle was disconcerting to many. As the North’s Non-Cooperation brewed a sense of unity, the Southern split sowed the seeds of separation. The current milieu sees this in Tamil Nadu's anti-BJP alliances (anti-Cong earlier) where Dravidian parties, mainly DMK, loop back to the Justice Party's anti-North playbook—a continuing reality of forging a path alone against the national tide.

Anyway, this awakening whispered reform from elite echoes, setting the stage for the high-stakes power plays of Dyarchy's dawn in 'Dravidanadu'.

Next | Rise & Rifts: Justice Party’s power plays & pitfalls

1 hour ago

4

1 hour ago

4

English (US) ·

English (US) ·