ARTICLE AD BOX

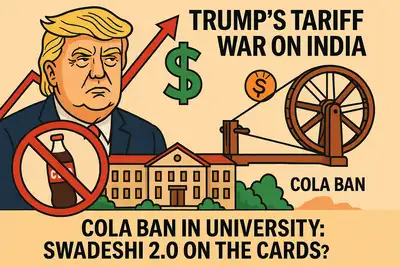

Lovely Professional University (LPU), based in Punjab, has banned American soft drinks including Coca-Cola and Pepsi from its campus. The decision was announced by LPU founder and Chancellor Ashok Kumar Mittal after the United States doubled tariffs on Indian goods to 50%.

Calling the move “hypocrisy and bullying,” Mittal declared that the boycott marked the beginning of a nationwide ‘Swadeshi 2.0’ campaign aimed at prioritising Indian products. Speaking at the Constitution Club in Delhi, he explicitly linked the step to the historic Swadeshi movement of 1905, when Indians rejected British goods during colonial rule. He urged students and citizens to adopt the same spirit today, framing the ban as a symbolic act of defiance against unfair trade practices.

A century-old echo in a 21st-century canteen

It is tempting to dismiss a campus soft-drink ban as theatre. Mittal’s invocation of 1905, when the Swadeshi movement asked students to boycott British goods, is not mere flourish; it is pedagogy by memory. If the first Swadeshi taught sacrifice through hand-spun cloth, Swadeshi 2.0 should test whether an educational institute can translate a tariff skirmish into a learning moment for students on self-reliance and power.

The question is not what disappears from a cafeteria refrigerator, but what enters a student’s frame of reference.

Symbolism as syllabus

In the classroom, symbols are not trivial; they are shortcuts to complex systems. A chilled can becomes a prism for demand curves, substitution effects, price elasticity, and non-tariff barriers. In political science, the same object becomes an entry point to debates on sovereignty and soft power.

History, meanwhile, supplies a longer lens: When Indian students in 1905 boycotted British textiles, the colonial government condemned it as economic sabotage; nationalists framed it as a principled fight for dignity.

Who, then, gets to call a boycott ‘principled’ and who gets to name it ‘protectionist’? The answer, history suggests, depends less on the object being boycotted than on the power to shape its narrative.

The ban acquires utility only if it travels from the canteen noticeboard to the seminar room and if students can interrogate it, not merely comply with it.

What makes an educational boycott ‘work’?

For a university, the test is not only about moral clarity but educational yield. Three conditions matter:

- Transparency of criteria: Students should know why a product is delisted and what benchmarks would reverse the decision; opaque virtue is poor pedagogy.

- Integration into coursework: Let the economics department model welfare impacts; let public-policy labs simulate tariff scenarios; let business schools invite Indian beverage entrepreneurs to discuss scaling against multinationals. A ban without a bibliography is a missed opportunity.

- Institutional consistency: If Swadeshi 2.0 is more than a slogan, it should reflect in vendor policies, research priorities, and student projects, not only in one aisle of a cafeteria.

The global campus tradition of boycott as pedagogy

Indian students are not the first to turn consumption into a curriculum. In the mid-1980s, students in American universities transformed their campuses into stages of global politics.

At Columbia University, Michigan, Berkeley, and dozens of others, protests demanded that university endowments divest from companies doing business in apartheid South Africa. The pressure was not in vain. By 1984, Columbia had partially divested, and by 1986, the US Congress passed the Comprehensive Anti-Apartheid Act, overriding President Reagan’s veto.

Scholars still credit student pressure as one of the sparks that made divestment a mainstream policy instrument. If apartheid divestment was about financial portfolios, the Coca-Cola campaigns of the 2000s were about daily consumption. Student groups under the “Killer Coke” banner accused the company of labour abuses in Colombia. Universities became battlegrounds: New York University, the University of Michigan, Oberlin College, and several European campuses suspended or cancelled contracts with Coca-Cola, sometimes pulling vending machines off their premises.The symbolism was sharp. A ubiquitous red can, once the icon of globalisation, was recast as evidence of corporate misconduct. Cafeterias and common rooms became proxy parliaments, where students debated whether brand contracts should reflect ethical commitments.The last lineFrom apartheid divestment to ‘Killer Coke’, the throughline is clear: When campuses frame consumption as citizenship, the effects ripple outward, sometimes altering corporate behaviour, sometimes shaping foreign policy, sometimes reinforcing nationalism. LPU’s ban sits within this global lineage, albeit on a smaller scale. What students choose to sip or shun is less important than whether they learn to decode the political economy behind the act

.png)

.png)

.png)

2 hours ago

2

2 hours ago

2

English (US) ·

English (US) ·