ARTICLE AD BOX

Kerala grapples with cadaver transplant shortage, putting the lives of 2,906 patients in need of vital organs at riskCase 1 : When most of her peers are engaged in schoolwork, hobbies or weekend plans, a 13-year-old girl is navigating a different reality — one that involves hospital corridors, heart monitors and a life on hold.

Her childhood paused abruptly three years ago, after she was diagnosed with a narrowing heart valve. Her classmates moved on to the eighth standard, but she has not sat in a classroom for three years. Yet, on the rare days, when health allows, her father — a fish seller — carries her to school and sits beside her — not wanting her to miss even a glimpse of normal life.Doctors at Sree Chitra Thirunal Institute of Medical Sciences confirmed her only chance at survival: A heart transplant.

But even the best efforts of renowned transplant surgeon Dr Jose Chacko Periyapuram could not find her a matching donor yet. The wait has turned their hope into a quiet endurance. "We went with big hopes,” said her father, in a tired voice. “But even the doctor has become helpless. We are just praying for a miracle.

”

Case 2: Three years ago, during a bustling Onam season in Thrissur, M B Jayan was tirelessly crafting intricate gold ornaments — designs that would soon adorn countless celebrations.

But behind all the sparkle, a silent battle was unfolding — each day ended with a fatigue Jayan could not ignore. Determined to fulfil his commitments before facing his own health, he postponed medical tests until after the festival. When Jayan finally did them, the diagnosis was devastating: Hepatitis. What followed were infections that affected his liver and kidneys, leaving him fighting for every breath.

Now, after two long years of waiting for a liver donor, Jayan faces a relentless struggle — weekly removal of eight litres of fluid from his swollen stomach, crippling breathing difficulties and a growing sense of uncertainty.

Jayan’s name is first on the transplant list but a suitable liver that became available months ago was given to a patient in a more critical condition. Jayan has shifted his treatment closer to his home in Thrissur, easing the financial burden but not the pain. “It cost me at least Rs 20,000 for one consultation and treatment at Amrita Hospital in Kochi,” he said. Now his wife is the sole breadwinner and she takes care of Jayan and their two sons.

He has been raising the money, Rs 22 lakh, needed for liver transplantation with the support of his friends and family members, but he is yet to find a suitable donor.

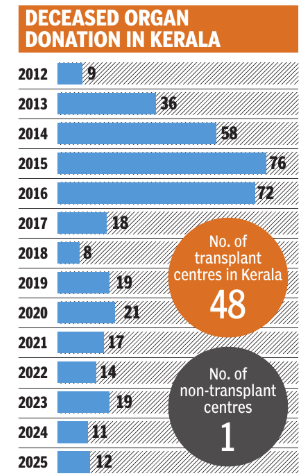

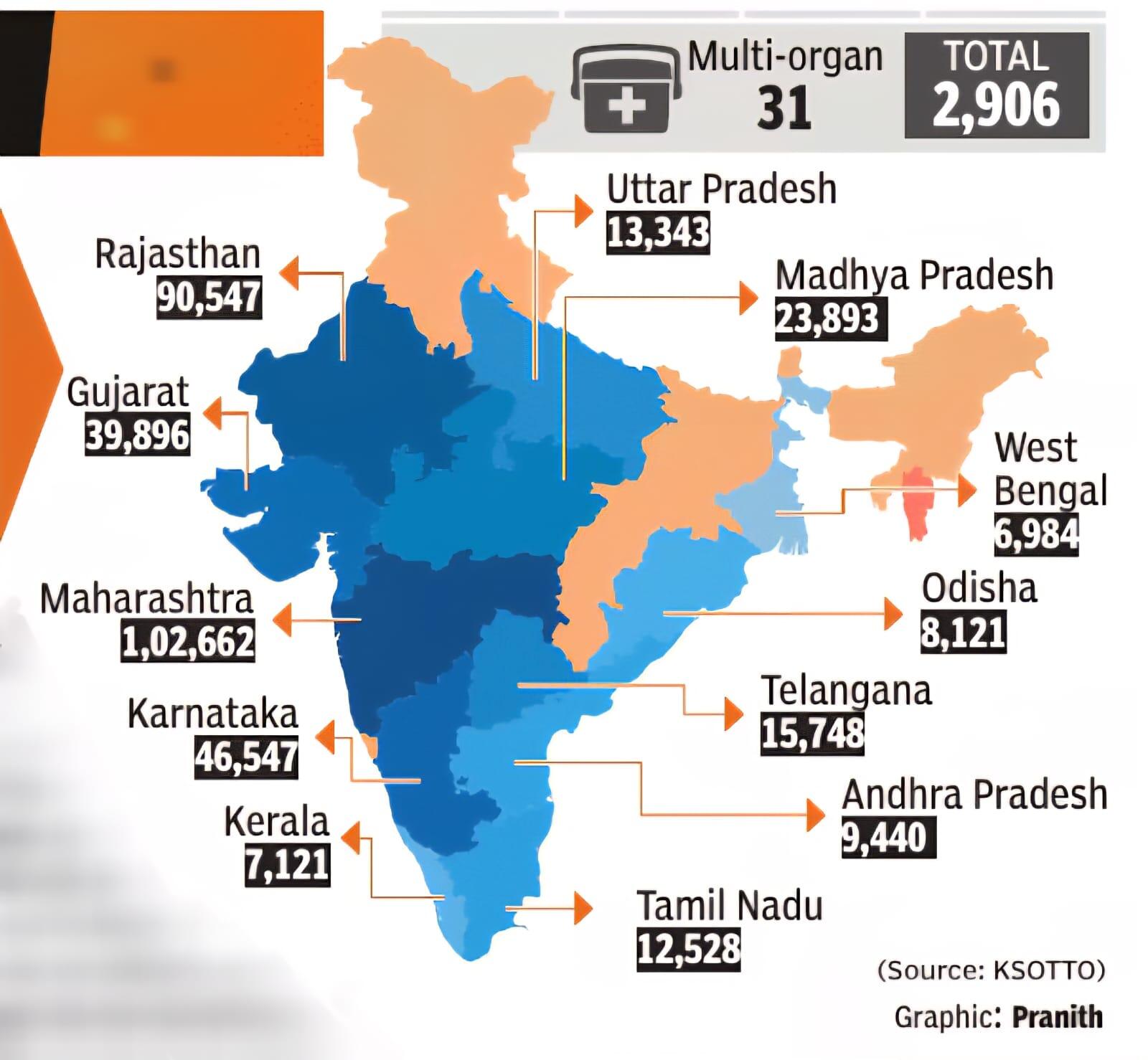

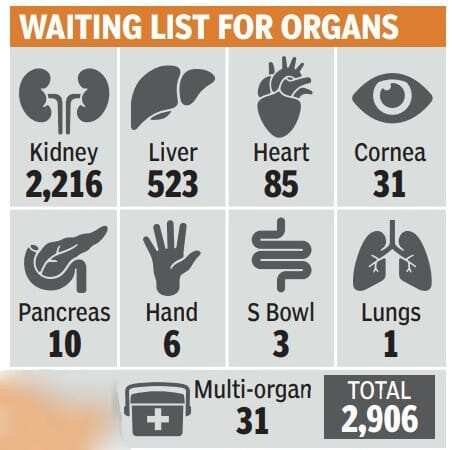

The Core Issue These are not just isolated cases being witnessed in the state. Statistics from Kerala State Organ and Tissue Transplant Organisation (KSOTTO) show 2,906 patients from across the state are waiting for organs to return to normal lives. Ten years ago, Kerala witnessed 70-80 cadaver transplants a year.

The state became a model for the rest of the country as the family members of deceased patients came forward to donate organs.

In the voluntary organ pledging registry, Kerala figured steadily in the top five.The situation took a curious turn after 2018. Malayalam film Joseph, released that year, had a serious impact on cadaver organ transplants. The film, which depicted a medical racket killing potential organ donors in staged accidents, created serious concerns and doubts among people. They became more reluctant to add their names to the organ donation registry as yearly cadaver transplants in the state dipped to 7-11. Some states have more than a lakh people in the organ donation registry while Kerala has only 7,121 and is currently ranked 11th in the country. Athma Thalam Liver Foundation of Kerala (LIFOK), an NGO that helps patients who underwent liver transplants, ran a campaign ‘Athma Thalam’ on the campus of a famous college in Ernakulam.

The idea was to promote voluntary organ donation and enrol youth’s names in national registry.“We anticipated a huge response from the 4,000-odd students there. But less than 800 expressed willingness to register. Most of the students were asking us what guarantee we could give that they would not be killed inside the hospital to retrieve organs. There is concern even among the youth,” says Babu Kuruvila of LIFOK.The massive decline in cadaver organ transplants has led to inordinate delays in getting organs. People are now approaching neighbouring states where the waiting period is less than four months.“We have referred several patients to Tamil Nadu and Hyderabad, where the waiting period is only 3-4 months. It is always better for them to get a new lease of life instead of succumbing after the agonising wait. There are several cases in which patients died of liver diseases after 8-10 months’ waiting because they did not get the organ in time,” said Kuruvila.Although treatment costs are a little high, people prefer to go to neighbouring states instead of waiting. “I registered for an organ at a leading hospital in Chennai because, at that time, the waiting period was too long in Kerala. I was not ready to risk my life by waiting for so long here. It was to my luck that I received the organ within a month,” said Ratheesh Nair, who underwent a liver transplant at Apollo Hospital in Chennai in 2018.There is also a concept among people that death occurs only when the heartbeat stops. Most doctors say it has become very difficult to convince people about the concept of brain death. Surprisingly, it is more difficult to convince educated people than those from ordinary backgrounds.“Take a look at the people who underwent cadaver transplants in the last few years. You can find that people from ordinary backgrounds have done this more because it is easy to convince them about how the organs are going to save the lives of others.

When you try to convince the educated, a thousand concerns are raised,” said a doctor who has performed several transplant surgeries.Declaring of brain deaths The movie, Joseph, is not the only reason for the drop in transplants. Hospitals have to take the first step to increase cadaver transplants, but it is not happening nowadays. A system must be in place for this, with proper organ transplant units at the retrieval centres, says KSOTTO executive director Dr Noble Gracious.Thousands of brain death cases occur across the state, especially in govt hospitals. But none of the doctors there is willing to declare them as brain deaths due to the complications that may arise after that, especially litigation. “Hospitals face a barrier in declaring brain deaths. It is a fact; we can't run away from it,” says Dr Gracious.Most doctors are not ready to take the risk of declaring a patient brain dead as their heart is still beating and they are breathing.

“Death has two definitions. A patient is dead for donating organs but not dead for stopping treatment. The confusion exists in ICUs, among doctors and with hospital management,” says Dr Gracious.“Firstly, in the hospitals, death determination using neurological criteria should be made a standard of care. Only then can we identify the core issue behind why cadaver transplants are not increasing in the state. Only then can we find where the problem lies — whether in society or not.

Without even declaring brain deaths, we cannot blame society alone as the reason behind the decline in this,” said Dr Gracious.It all started with a public interest litigation filed in 2016 by Dr S Ganapathy of Kollam who alleged malpractices in organ transplantation by hospitals, specifically that patients were being declared brain dead prematurely to harvest organs for transplant. The Kerala high court ordered hospitals to strictly adhere to medical ethics and the Transplantation of Human Organs (THO) Act of 1994, and ensure proper brain death certifications.

The govt was also asked to make the rules stringent for brain death declaration. As a result, the doctors are now hesitant in taking up the burden of declaring brain deaths on their shoulders and are not promoting harvesting organs from the dead.“When doctors are dragged into litigation and they are not given any support during the legal battle, who will take the risk?” asks Dr Periyapuram of Lisie Hospital in Kochi.The core issue lies in this fact. Now when KSOTTO asks for statistics from hospitals on the number of brain deaths in each month, their reply is ‘zero’.As per State Crime Records Bureau (SCRB) statistics, 3,714 lives were lost on the roads of Kerala in 2024. However, the number of deceased organ transplants that occurred in Kerala in 2024 is 11.An initiative which can save the lives of thousands of patients is still in its nascent stage even after 12 years. A proper system to eliminate social stigma, adequate protection for doctors who declare brain death and a dedicated unit for organ transplants in hospitals can only save the crisis.

.png)

.png)

.png)

2 days ago

6

2 days ago

6

English (US) ·

English (US) ·