ARTICLE AD BOX

Milky Way galaxy (Source: NASA)

For decades, the search for extraterrestrial life has revolved around a simple rule: follow the water. If a distant planet has liquid water, and perhaps oxygen, it is flagged as potentially habitable. But new research led by scientists at ETH Zurich suggests that this long-standing strategy may be incomplete. A planet can have oceans and continents, the researchers argue, and still be chemically incapable of supporting life. The real constraint may lie much deeper, in the chemistry of a planet’s formation.

A Chemical Goldilocks Zone beneath the surface

The study, published in Nature Astronomy under the title “The chemical habitability of Earth and rocky planets prescribed by core formation”, was led by Dr Craig R. Walton, a postdoctoral researcher at the Centre for Origin and Prevalence of Life at ETH Zurich, alongside Professor Maria Schönbächler and colleagues. Their central claim is precise: life depends not just on water and oxygen, but on whether two critical elements, phosphorus and nitrogen, remained accessible in a planet’s mantle during its earliest formation. Phosphorus is required to build DNA and RNA, the molecules that store and transmit genetic information. It also plays a key role in cellular energy systems. Nitrogen, meanwhile, is an essential component of proteins, the structural and functional building blocks of cells.

Without both, life “as we know it simply cannot form”.

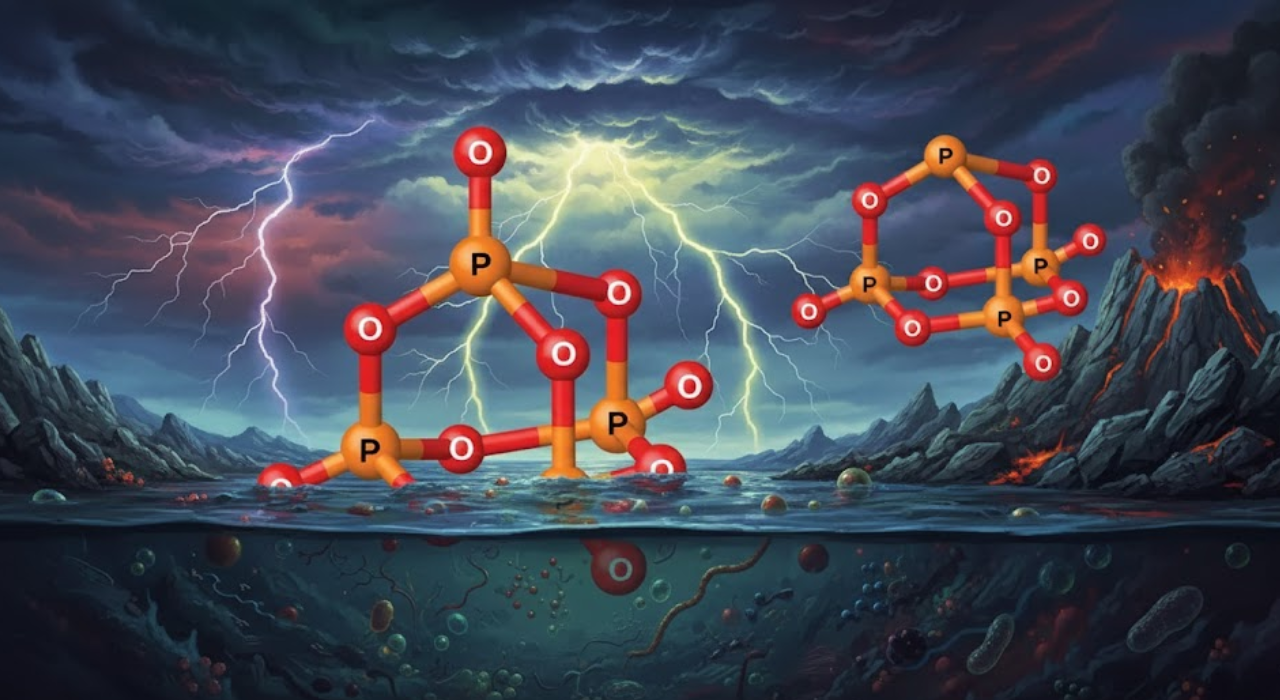

Phosphorus and nitrogen are critical for life: phosphorus forms DNA, RNA, and ATP for energy, while nitrogen builds proteins./ AI Illustration

“During the formation of a planet’s core, there needs to be exactly the right amount of oxygen present so that phosphorus and nitrogen can remain on the surface of the planet,” Walton explained. Young rocky planets begin as molten bodies. As they cool, heavy elements such as iron sink to form the core, while lighter material forms the mantle and crust. At the same time, oxygen levels determine how elements chemically partition between metal and rock. If oxygen is scarce, phosphorus bonds with iron and sinks into the core, effectively removing it from the surface environment. If oxygen is too abundant, phosphorus stays in the mantle, but nitrogen is more likely to escape into the atmosphere and eventually be lost to space. “Having too much or too little oxygen in the planet as a whole – not in the atmosphere per se – makes the planet unsuitable for life because it traps key nutrients for life in the core,” Walton told the Daily Mail. “A different oxygen balance means you have nothing to work with left at the surface when the planet cools and you form rocks.” Using numerical modelling, the team identified what they describe as a very narrow “chemical Goldilocks zone,” an intermediate oxygen range in which both phosphorus and nitrogen remain in the mantle in quantities sufficient for life.

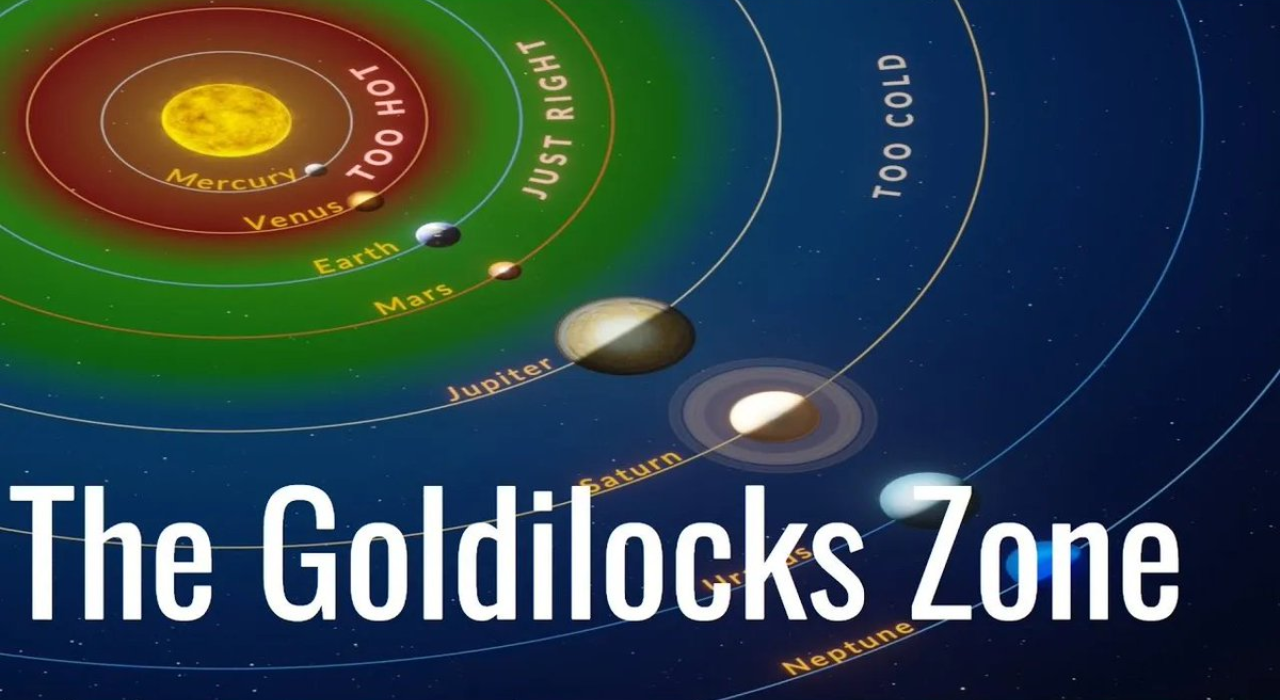

A planet’s ‘Goldilocks zone’ for life requires just the right amount of oxygen to keep phosphorus and nitrogen available/ Image: X

“Our models clearly show that the Earth is precisely within this range,” Walton said. “If we had had just a little more or a little less oxygen during core formation, there would not have been enough phosphorus or nitrogen for the development of life.” Earth appears to have struck that balance around 4.6 billion years ago.

Rethinking what makes a planet habitable

The findings suggest that many planets previously considered promising may be chemically unsuitable for life from the outset, even if they contain water. While no known life can survive without liquid water, the researchers argue that using oxygen or water alone as markers of habitability may be misleading. A planet’s total oxygen balance during its formation, not simply atmospheric oxygen, determines whether life-critical elements remain available. Walton warned that this may significantly narrow the number of habitable worlds in the universe. He suggested there may be just one to 10 per cent as many habitable planets as previously estimated. “It would be very disappointing to travel all the way to such a planet to colonise it and find there is no phosphorus for growing food,” he said. “We’d better try to check the formation conditions of the planet first, much like ensuring your dinner was cooked properly before you go ahead and eat it.” Closer to home, the research suggests that Mars lies just outside this chemical zone. Mars appears to contain relatively abundant phosphorus, but significantly lower nitrogen levels near the surface. In addition, harsh salts and other surface chemistry make the soil inhospitable.

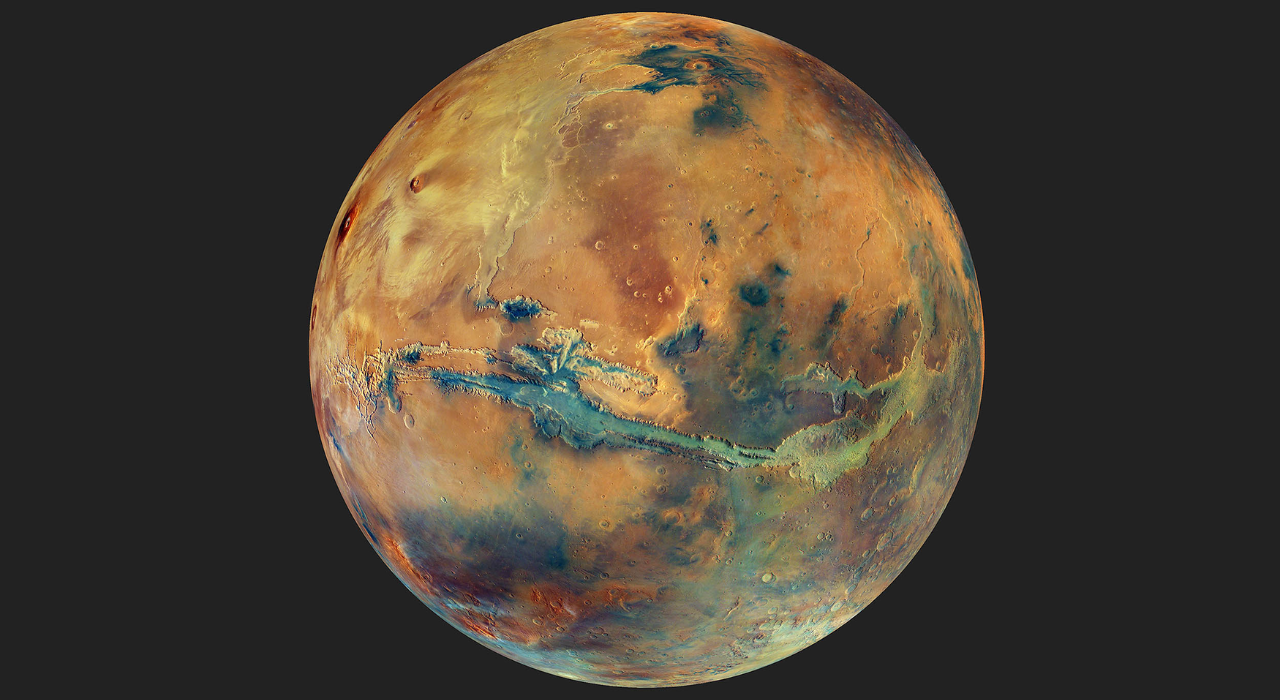

Mars has enough phosphorus but lacks sufficient nitrogen, making its surface chemically unsuitable for supporting life as on Earth/ Mars in its true color/ Image: Earth.com

“Mars is fairly similar to Earth, and its formation conditions mean there is more phosphorus, not less. This means growing food there might be relatively easy,” Walton said. But he added that the nitrogen deficit and surface chemistry pose major challenges: “It is not that different, but it is not currently habitable, Elon Musk will have to come up with a clever way to change the composition to grow food there.”

Searching the right stars

Directly measuring the internal chemistry of distant rocky planets remains extremely difficult. However, astronomers can infer likely planetary compositions by studying host stars. Planets form from the same material as their parent stars. The oxygen abundance and overall chemical structure of a star therefore shape the composition of its planetary system. Solar systems whose stars closely resemble our Sun may offer better odds. “This makes searching for life on other planets a lot more specific,” Walton said. “We should look for solar systems with stars that resemble our own Sun.” The work reframes the long-running search for life beyond Earth. Water remains necessary. But it may not be enough. A planet’s fate, whether sterile or living, could hinge on a delicate chemical balance struck in its first molten moments, long before oceans, atmospheres or continents ever formed.

1 hour ago

4

1 hour ago

4

English (US) ·

English (US) ·