ARTICLE AD BOX

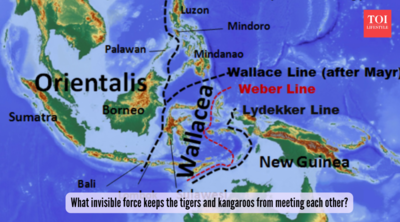

Alfred Russel Wallace observed a distinct biological divide in the Malay Archipelago, now known as the Wallace Line. Recent studies reveal that Asian species, adapted to wet tropics, successfully migrated east to Australia, while Australian marsupials struggled with the humid Indonesian islands, solidifying this one-way biological barrier.

Have you ever looked at a map and wondered why tigers roam on one island while kangaroos hop just miles away on another and never meet one another? It's like nature drew strict neighbourhood lines, keeping wildlife worlds apart despite shallow seas between them.

Alfred Russel Wallace, a naturalist and explorer, spotted this quirky divide 160 years ago, igniting a sense of mystery and a puzzle that has hooked scientists ever since. Today, with advanced technology for researching ancient climates, researchers finally have an answer to why Asia's beasts invaded Australia but not the reverse.But what exactly made this happen? Did nature naturally draw a line, or is it something else? It might actually be colliding continents, ice ages, and rain that acted like bouncers at a club. This isn't just old history; it's a cheat sheet for our warming world, showing how weather changes can redraw life's borders overnight. Let’s dig in to find out!

Wallace Line (Photo: Wikimedia commons)

But what exactly made this happen? Did nature naturally draw a line, or is it something else?

It might actually be the colliding continents, ice ages, and rain that acted like bouncers at a club. This isn't just old history; it's a cheat sheet for our warming world, showing how weather changes can redraw life's borders overnight. Let’s dig in to find out!

What is the Wallace line?

Back in 1854, self-taught naturalist Alfred Russel Wallace travelled the Malay Archipelago chasing the origin of species. Over eight gruelling years, he travelled 14,000 miles, collecting 125,660 specimens - thousands of new insects, birds, and mammals.

for Western science, according to a ZME Science report. He'd kneel for hours in wet sand and decay, battling malaria and dysentery to catalogue tropical wonders.He was amazed in 1856 when he crossed from Bali to Lombok. Bali had Asian birds like barbets and woodpeckers. And as soon as he reached Lombok, the flora and fauna changed, and Australian cockatoos and megapodes became prevalent. This sharp split inspired the Wallace Line, carving Indonesia into Asian and Aussie zones.

Local helper Ali's collecting skills were key to Wallace kickstarting biogeography - linking life's spread to Earth's geology.

How did this happen?

About 50 million years ago, Australia broke from Antarctica and drifted north, slamming into Asia's edge. This tectonic tango birthed Indonesia's fiery islands, but deep trenches in Wallacea blocked most land critters.Then, 35 million years back, the Drake Passage opened, sparking the Antarctic Circumpolar Current.

Temperatures cooled, and Antarctica iced over. Eocene warmth faded into Oligocene drought, changing habitats and testing who could cross the humid island hopscotch between Sunda (Asia) and Sahul (Australia).

Why don’t Australian Marsupials and Asian Mammals meet each other?

A 2023 ANU–ETH Zurich study ran Gen3SIS models on 20,000 vertebrates over 30 million years. To their surprise, they found that Asian species survived in the wet tropics, spreading east to Australia. Aussie ones, baked dry during their isolating drift, choked on Wallacea's steamy forests - a group of mainly Indonesian islands."Asian fauna were already well-adapted... so that helped them settle in Australia," said lead researcher Dr Alex Skeels. Marsupials couldn't hack the humidity westwards, as dispersal rates were twice as high from Asia to Australia. Cooling killed off weaker species, locking the divide.

Wallace's Line delineates Australian and Southeast Asian fauna (Photo: Wikimedia Commons)

Why the one-way traffic

Small critters like shrews and rodents island-hopped with ease, but big kangaroos and koalas couldn't make the jump. "If you travel to Borneo, you won't see any marsupial mammals, but head to neighbouring Sulawesi and you will," Skeels pointed out.The steamy tropical dampness suited Asia's humidity-loving species far better than Australia's dry-climate crew. Deep ocean trenches and volcanic chains added extra roadblocks. This one-way street saw far more Asian animals crossing over, locking in the Wallace Line and turning potential bridges into unbreakable barriers.Photos: Wikimedia Commons

1 hour ago

3

1 hour ago

3

English (US) ·

English (US) ·