ARTICLE AD BOX

Nalanda University, a revival of ancient learning, has opened its doors, blending historical reverence with modern sustainability. This international institution, a UNESCO World Heritage site, focuses on Buddhist studies, ecology, and humanities. It actively engages with local communities, fostering mutual growth and empowerment, embodying a spirit of interdependence and knowledge sharing.

Bricks can be storytellers - and at the ruins of Nalanda, they certainly are.Since the 5th century CE, more than 600 years before Europe's oldest university was founded in Italy, Nalanda was the world's premier residential academy for Buddhist learning, drawing monks and scholars from far-off China and across South-East Asia.

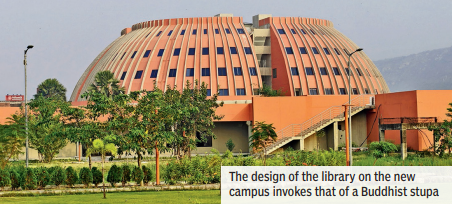

But the monasteries and temples were ravaged and its manuscripts burnt by Turkish invaders in the 12th century CE. Yet the magnitude and symmetry of the surviving structures - masterpieces of "magic bricks" that time couldn't corrode - bear testimony to the awe they once inspired.Even today, the vast complex, a Unesco World Heritage site since 2016, carries the feel of an epic poem written in tragic red exuding, at the same time, a majestic serenity.About 15km from the ruins, the past has quietly returned in a new avatar. The tall boundary wall topped with barbed wire and the imposing iron gate give the impression of a high-security prison, but the new Nalanda University campus looks more like a homage to its ancient predecessor. Like the ruins, the spartan buildings are overwhelmingly red, creating a familiar, almost monastic, mood. The impressive library structure is shaped like a stupa.

Hiuen Tsang might have approved.

Surrounded by the unassuming Rajgriha hills, the campus is spread over 455 acres - 300 acres of green and 100 acres of water bodies. Only 55 acres, just 12%, are earmarked for construction. The buildings are angular, well ventilated, and filled with natural light, its funnel-shaped roofs designed to aid water conservation. The Sushma Swaraj auditorium is state-of-the-art. Quite a few buildings, including the gymnasium, overlook water bodies.

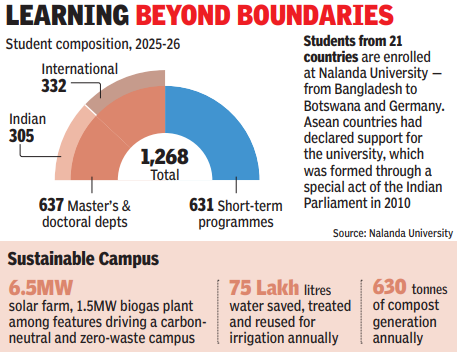

The campus also has a chanting hall where even conversations feel like hymns. A little away, monks in orange robes ride past in bicycles, giving the place an international touch. About 90% of students in the school of Buddhist Studies are from abroad. Nearby, black fowls glide on shimmering waters.This is also the country's first "net zero" university. Which, ecologically, translates into a green, carbon-neutral and sustainable campus.

Fossil fuel vehicles are not allowed beyond visitors' parking areas. Battery carts ply. Many students use bicycles. So does the vice-chancellor. This is also a polythene-free campus with a clutch of biowaste collection points. The university has its own solar farm and biogas plant.

Only surface water is used. "A net zero campus is really cool," says Antony Kimnai Mwangi, who has come from Nairobi in Kenya to study environmental sciences and ecology.

The seed of the new university can be traced to a speech by (then) President APJ Abdul Kalam in Bihar Legislative Assembly in 2006. Kalam spoke of the need to revive Nalanda as a centre of learning. The idea enthused CM Nitish Kumar, who belongs to the same district. Land was gradually acquired on a 99-year lease and handed over to the Centre.The university was formed through a special act of Parliament in 2010. It is supported by the Union ministry of external affairs, but found its shape as an international collaboration.

Earlier, at the 4th East Asia Summit (EAS) in Thailand in 2009, 17 member countries issued a joint statement supporting the establishment of Nalanda University as "a non-state, non-profit, secular and self-governing international institution".Nobel laureate economist Amartya Sen functioned as its first chancellor from 2010-16. The university initially operated from the city nearby, with the campus becoming functional in 2019. Full-fledged operations started after its official inauguration by PM Narendra Modi in Aug last year.The partnership, mostly funded by India but also aided by the other participating nations, aim "to improve regional understanding and the appreciation of one another's heritage and history". It is also a diplomatic outreach. "Ancient Nalanda engaged intellectually with Asian wisdom and traditions. We are trying to revive that old knowledge with emphasis on modern instruments like Act East policy, East Asia Summits, Asean etc," says vice-chancellor Sachin Chaturvedi.

(see interview).Ancient Nalanda, wrote Romila Thapar in the book, A History of India, concentrated on subjects such as "grammar, rhetoric, prose and verse composition, logic, metaphysics and medicine". The new university syllabus reflects a striving to fashion its own personality while harnessing the values and virtues of the past.

The university does not offer engineering or business courses, barring an MBA in sustainable development.

Programmes - PhD, post-graduate, diploma and certificate - are mostly in history, religious philosophy, ecology, literature, etc. Among other courses, there's also a master's in Hindu studies. Curriculum is cross-disciplinary; so are some faculty members. Assistant professor Pranshu Samdarshi teaches Buddhist studies, Hindu studies, and Historical studies.

Classes are open to everyone, irrespective of discipline.The School of Buddhist Studies, Philosophy and Comparative Religions typifies the university's broader spirit. "We make students study primary sources from original, classical texts in Sanskrit, Pali and Tibetan languages with the rigour of logic and epistemology," says Pooja Dabral, who teaches Buddhist philosophy.The new university is also collecting books and manuscripts, both in real and digital form.

Some aren't in the best of health. "Next year we will also use AI to decipher manuscripts," says Samdarshi.Debates, discussions (vaad-samvaad) and a spirit of continuous inquiry are part of the pedagogy fabric. Topics such as, "Tangible heritage vs literary narratives: Which better sustains the Nalanda spirit?", are argued by the debating club. Ancient Nalanda luminaries such as Nagarjuna, Buddhapalita, Candrakirti, Silabhadra, Bhaviveka, and Santideva are discussed.

"What makes the debate vibrant isn't just the arguments, but the mutual respect for complexity, a true Nalanda tradition," Dabral says.Buddhist studies students come from diverse backgrounds, ranging from computer science to monastics, and from countries like Laos, Indonesia, Bangladesh and the UK, she says. The MBA course on sustainable development and management has attracted students from 11 countries.

"We celebrate national days of all partnering countries," says Samdarshi.The old Nalanda university started in the Gupta period and functioned from 5th century CE for the next 700-odd years. It sustained itself, among other things, on revenues collected from nearby villages. "These villages and estates covered the expenses of the university, which was thus able to provide free education and residential facilities for most of its students," wrote Thapar.

Anand Kumar, who teaches sustainable development and management, describes the hallowed university as "a state of interdependence".Among the standout features of the new university is "sahbhagita", an initiative to engage and improve neighbouring villages and schools. "When I took over some months back, I saw some discontent among villagers who had lost their land to the university. We decided to connect with them," says Chaturvedi.

The self-sufficient university now shares water and electricity with them. A school needed bricks for a boundary wall.

Compress bricks, produced to construct the campus, were offered. The joy of giving at work.This July, students and faculty started surveying five adjacent villages (Pilki, Mahadeva, Mahuallah, Kubdi and Jatti) to collect data with the aim of creating a Nalanda University self-help group. Data was also gathered from Nepura, a weavers' village, and local bazaars, where home-made products such as pottery, cots and spices are sold."Through these surveys, we are trying to find out what skills they possess and what they are interested in learning. We are exploring regional art, craft and other cultural heritage so we can utilise them as a means of uplifting and empowering local communities, especially women," said Garima Khansili, a post-doctoral fellow in archaeology.In Sept, about a dozen women attended a sculpture-making workshop helmed by an expert.

Similar workshops are being planned for Madhubani painting and embroidery. "The university shall procure the items created during these workshops and also, in the long run, facilitate participants' access to external markets," she says. To boost employment prospects, foreign languages such as Japanese and Vietnamese are taught at the city centre to locals for a nominal fee.Nearby, 14 govt schools have also been engaged. Surendra Prasad, headmaster of the middle school at Mahadevpur, says NU faculty participated in a parent-teacher meeting last week and discussed methods to stop student dropouts.

"They also spoke of shifting from chemical fertilisers to vermicompost," says Prasad. Tanoj Kumar, a marginal farmer in Mudaffar village, says he has received over 20kg of compost, seeds and plants for green farming from the university. "It is good to see them taking so much interest in our lives," he said.

Students, too, have gained. Devyansh Pandey, a student in the school of ecology and environmental studies, says the interactions have helped them understand the histories of farming in the area.

"We have learnt how seasonal changes are affecting them and how they are adjusting to new needs. It is a mutual symbiotic growth," he says.Shweta (she uses only her first name) teaches social sciences. She was invited to attend a talk on the first Jain, Tirthankar Rishabhdev. Schoolkids were invited for a function on Dr Rajendra Prasad and culinary art and participated in a quiz. "Students in govt schools come from underprivileged backgrounds. Some even drop out during harvesting season. These trips have excited their curiosity. Attendance has improved," she says.What's the takeaway then? Elite institutions need not just restrict themselves to classrooms but can become drivers of change on the ground.

1 hour ago

4

1 hour ago

4

English (US) ·

English (US) ·