ARTICLE AD BOX

The recently-concluded Assembly polls in Bihar could have ramifications that may resonate well beyond the political arena. The first signs emerged on Tuesday during the Supreme Court's hearing of petitions against the SIR exercise in Tamil Nadu and West Bengal.

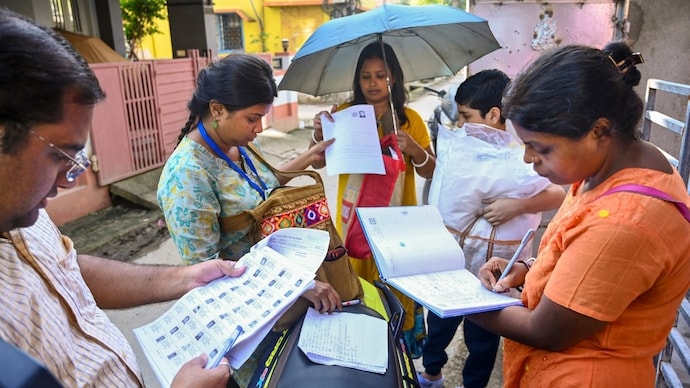

The Supreme Court’s cautious approach to challenges against SIR in Tamil Nadu and Bengal signals a tough road ahead for petitioners. (PTI Photo)

The Supreme Court’s cautious approach to challenges against the Special Intensive Revision (SIR) of electoral rolls in Tamil Nadu and West Bengal signals a tough road ahead for petitioners.

The recently-concluded Assembly polls in Bihar could have ramifications that may resonate well beyond the political arena, especially in India’s legal corridors.

The first signs emerged on Tuesday during the Supreme Court’s hearing of petitions against the SIR exercise in Tamil Nadu and West Bengal.

THE CONTEXT AND COMPLAINTS

Petitions against the SIR have been filed by DMK leader RS Bharathi , CPI(M) leader P Shanmugam, Tamil Nadu Congress leader K. Selvaperunthagai, Trinamool Congress's Dola Sen, and Bengal Congress leader Subhankar Sarkar.

Senior Advocate Kapil Sibal, appearing for petitioners from both states, has raised several concerns about the revision process in Tamil Nadu.

He argued that the exercise will be conducted at a time when the state faces heavy monsoon rains and widespread agricultural activity, leaving many citizens and officials occupied. He also pointed out that the revision period coincided with Christmas holidays and Pongal festivities, during which large sections of the population would not be available to participate.

In West Bengal, Sibal said the situation there was worse as many areas lacked basic connectivity.

SUPREME COURT OBSERVATIONS

Responding to the petitioners, the Supreme Court made two key observations:

We should enable the exercise so that it reaches the common man in the easiest manner.

A constitutional authority was undertaking the exercise and said that any functional deficiencies could be rectified.

A bench of Justices Surya Kant and Joymalya Bagchi pointed out the petitioners appeared to be treating the revision as if the Election Commission of India (ECI) was creating a fresh voter list. The bench said it is aware of ground realities, and ECI will answer the questions about procedural challenges.

Significantly, the bench backed the Election Commission’s right to have layers of privacy over the data.

WHY SUPREME COURT OBSERVATIONS ARE IMPORTANT

The pointed questioning of the apprehensions suggests a judicial inclination that may not be entirely amenable to the petitioners’ arguments this time.

This stance marks a subtle but significant shift in the Court’s approach compared to other SIR-related litigations, such as in Bihar.

The Court’s queries imply that the Court is probing whether the objections raised amount to genuine concerns of disenfranchisement or if they mask political or strategic interests.

EMPHASIS ON RECTIFICATION

Rather than entertaining calls to halt the SIR process outright, the Supreme Court has emphasised the opportunity for “rectification of deficiencies.”

This signals the Court’s preference for addressing procedural and operational issues through adjustments and oversight, rather than suspending the exercise.

Such a stance places the burden on petitioners to demonstrate substantive harm rather than procedural inconvenience.

JUDICIAL RESPECT FOR ELECTION COMMISSION MANDATE

The tone of the Supreme Court’s observations indicates a nod to the Election Commission’s mandate and discretion to conduct electoral rolls revision. The court appears to trust the Commission’s capacity to balance local conditions with the imperative of electoral integrity.

IMPLICATIONS FOR PETITIONERS

Given this context, petitioners challenging the SIR in Tamil Nadu and West Bengal may face an uphill battle in persuading the Supreme Court to grant substantive relief. The court’s focus on remedy rather than suspension, alongside its probing attitude toward the apprehensions raised, suggests limited judicial sympathy for arguments predicated on timing and logistical challenges alone.

This approach differs from the Court’s relatively more interventionist stance in Bihar, where detailed procedural safeguards were mandated.

In Tamil Nadu and West Bengal, the burden of proof on the petitioners seems heavier, requiring clear evidence of voter disenfranchisement or constitutional violation over and above administrative concerns or political objections.

THE BIHAR EFFECT?

The Supreme Court’s more sceptical and probing stance toward the apprehensions around the SIR in Tamil Nadu and West Bengal is supported by the experience of Bihar’s SIR exercise in 2025.

In Bihar, the SIR process led to the removal of nearly 65 lakh voters. Despite initial fears and political agitation alleging voter disenfranchisement, the final outcome was a record voter turnout of 66.9 per cnt, with women voters showing even higher participation than men.

This historic voter engagement in Bihar was viewed as a strong endorsement of the SIR process enhancing electoral integrity and citizenship participation rather than suppressing votes.

Against this backdrop, the Supreme Court's pointed questioning of the petitioners in Tamil Nadu and West Bengal reflects confidence drawn partly from Bihar’s example.

- Ends

Published By:

Karishma Saurabh Kalita

Published On:

Nov 13, 2025

1 hour ago

5

1 hour ago

5

English (US) ·

English (US) ·