GUWAHATI A new study has identified at least two native plants that have joined invasive species to alter the riverine ecosystem of eastern Assam’s Dibru-Saikhowa National Park (DSNP), the only habitat of feral horses in India.

These species have added to the changes in the grassland-dominated DSNP landscape, largely attributed to the recurring Brahmaputra River floods and increasing anthropogenic pressures from forest villages located within its boundaries, the study said.

The native “grassland invaders” are Bombax ceiba and Lagerstroemia speciosa, flowering trees known as Simalu and Ajar in Assamese. Their impact on the local vegetation has been as worrying as that of the invasive species, which include shrubs Chromolaena odorata and Ageratum conyzoides, herb Parthenium hysterophorous and climber Mikania micrantha.

The study titled Grasslands in Flux, analysing the land use and land cover (LULC) changes in Dibru-Saikhowa from its designation as a national park in 1999 through 2024, was published in the latest issue of Earth, an international, peer-reviewed journal on earth science.

The authors of the study are Imon Abedin, Sanjib Baruah, Pralip Kumar Narzary, and Hilloljyoti Singha from Bodoland University, Tanoy Mukherjee from Zoological Survey of India, Shantanu Kundu from South Korea’s Pukyong National University, and Joynal Abedin from Women’s College, Tinsukia.

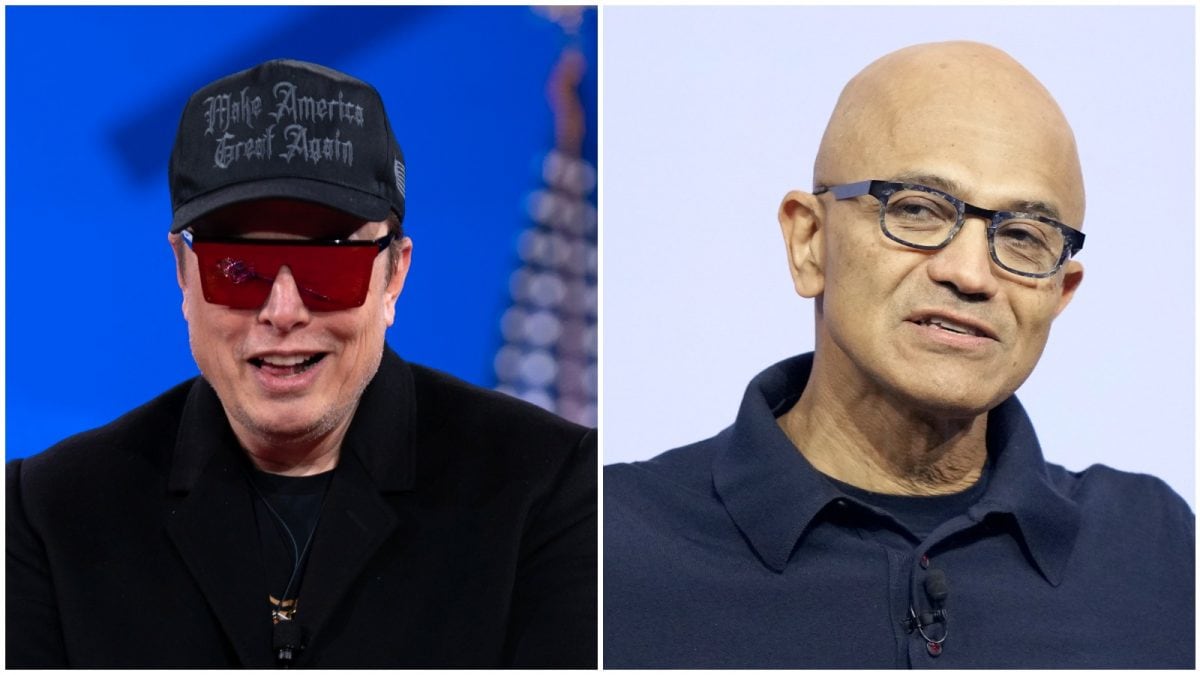

Native and invasive plant species are changing the riverine ecosystem of eastern Assam’s Dibru-Saikhowa National Park, the only habitat of feral horses in India. | Photo Credit: Special arrangement

The researchers used remote sensing and geographic information systems to analyse the LULC changes in DSNP, an island-like formation between the Brahmaputra to the north and the Dibru River to the south.

According to their study, grasslands covered 28.78% of the 425 sq. km DSNP in 2000, followed by semi-evergreen forests (25.58%). By 2013, shrubland became the most prominent class (81.31 sq. km), and degraded forest expanded to 75.56 sq. km.

“During this period, substantial areas of grassland (29.94 sq. km), degraded forest (10.87 sq. km), semi-evergreen forest (12.33 sq. km), and bare land (10.50 sq. km) were converted to shrubland. In 2024, degraded forest further increased, covering 80.52 sq. km (23.47%),” the study said.

This change was the outcome of the conversion of 11.46 sq. km of shrubland and 27.48 sq. km of semi-evergreen forest into degraded forest, indicating a substantial and consistent decline in grassland, the study noted.

Forest degradation, even without a decrease in forest area, can lead to loss of biodiversity, threaten the survival of local fauna, and reduce carbon storage, potentially intensifying climate change.

Grassland recovery sought

Dibru-Saikhowa, straddling the Dibrugarh and Tinsukia districts, was named after the Dibru Reserve Forest and Saikhowa Reserve Forest that were amalgamated to create a wildlife sanctuary in 1995. UNESCO declared the area a Biosphere Reserve in 1997, two years before it became a national park.

The study stated that the changes in the “natural structure and function” of the DSNP landscape pose a serious threat to the survival of grassland-obligate faunal species, many of which are already globally threatened due to ongoing habitat loss.

Native and invasive plant species are changing the riverine ecosystem of eastern Assam’s Dibru-Saikhowa National Park, the only habitat of feral horses in India. | Photo Credit: Special arrangement

“The concern is heightened by the fact that numerous species are endemic to the grasslands found in the floodplains of this region. Notable species which are rapidly decreasing include the Bengal florican (Houbaropsis bengalensis), hog deer (Axis porcinus), and swamp grass babbler (Prinia cinerascens),” the study said.

The national park is also home to some 200 feral horses, which are descendants of military horses abandoned during World War 2.

The study recommended a targeted grassland recovery project that would encompass the control of invasive species, improved surveillance, increased staffing, and the relocation of forest villages to reduce human impact and support community-based conservation efforts.

“Protecting the landscape through informed LULC-based management can help maintain critical habitat patches, mitigate anthropogenic degradation, and enhance the survival prospects of native floral and faunal assemblages in DSNP,” it concluded.

.png)

.png)

.png)

8 hours ago

6

8 hours ago

6

English (US) ·

English (US) ·