ARTICLE AD BOX

Bharat Sevashram Sangha monks head to an SIR hearing centre especially set up for them in Kolkata

Monks and nuns may have renounced all trappings of worldly life — and many of them do not vote — but they, too, are being called for SIR (Special Intensive Revision) hearings, mainly for listing their spiritual gurus’ names under the ‘name of parent’ column in the electoral records.Taking cognisance of the inconvenience faced by monastic orders, the Election Commission (EC) has directed district election officers (DEOs) to conduct hearings at ashrams and religious institutions, instead of asking monks to travel to designated centres. In cases where supporting documents are unavailable, the DEO — who is the district magistrate — has been authorised to act as a quasi-judicial authority and clear voter applications.The issue surfaced after several monks received hearing notices due to address and identity mismatch, caused by years of transfers between ashrams. Eighty-two-year-old Swami Muktikamananda, adhyaksha of the century-old Gadadhar Ashram (Ramakrishna Math) in Bhowanipur, south Kolkata, said his voter ID card and Aadhaar were linked to a Ramakrishna Math in Bankura (more than 200km from Kolkata), where he had stayed for an extended period.

“I was initially asked to attend a hearing in Bankura, but after intervention by electoral officials, I submitted my enumeration form in Bhowanipur itself,” he said.Last Wednesday, around 90 monks attended a special SIR camp organised at Belur Math, with hearings held at the Abhedananda Convention Centre. Participants included residents of the Belur headquarters as well as monks from centres such as the Ramakrishna Mission Ashrama in Narendrapur.

While monks of the Ramakrishna Math and Mission do not vote, they seek inclusion in electoral rolls to avoid complications in visa applications and administrative work.Monks from Bharat Sevashram Sangha (BSS) and Iskcon, many of whom do vote, have also received SIR notices. Swami Mahadevananda of BSS said several monks had listed founder Acharya Swami Pranavananda’s name as their parent, triggering document mismatches.

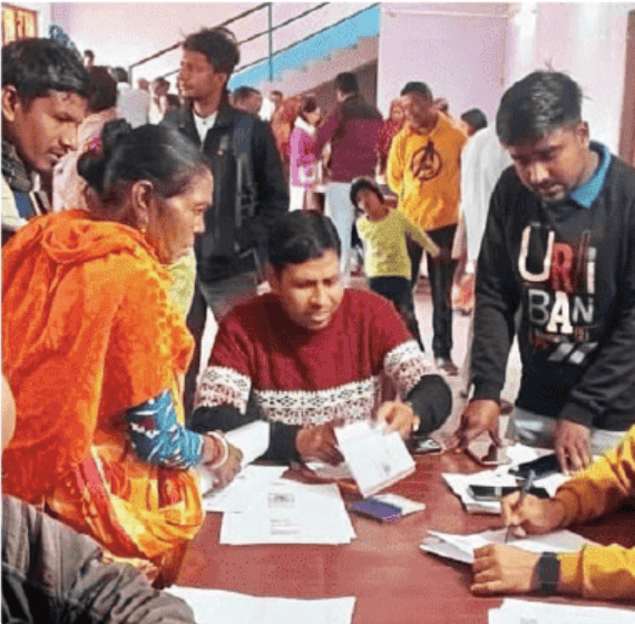

General secretary Dilip Maharaj said monks without passports attended a special hearing on Jan 20 at the Ballygunge headquarters.Iskcon spokesperson Radharamn Das said monks who had earlier voted in Kolkata had been asked to submit fresh documents from their native places across India and abroad.Avoiding elephant routesVoters in Jhargram and West Midnapore — in Bengal’s Jangalmahal, about 150km from Kolkata — have, over the years, learnt how to coexist with elephants.

It’s a sort of mutual respect, born out of a certain wariness — and a tacit understanding: “Stay out of my hair, and I’ll stay out of yours.”During the SIR, regular elephant movement has coincided with a sudden rise in human movement — residents with voter detail anomalies are having to travel far and wide to arrive at hearing centres, a highly unsafe exercise. And, so, the poll body said yes when the two district administrations wanted to set up multiple hearing centres, located near human settlements, across six assembly constituencies.

Similar arrangements are also being planned in elephant-heavy pockets of North Bengal.In West Midnapore, voters from select Jangalmahal villages will attend hearings at the Pirakata Community Hall, under the jurisdiction of Salboni police station. Salboni BDO Ruman Mondal said residents of villages such as Kalsibhanga, Satpati, Kalaimuri, Garmal, Lalgaria and Bhimpur were directed to appear at the new centre from Jan 15. Medinipur Sadar subdivisional officer Madhumita Mukherjee said it was a deliberate decision to choose the additional centres based on how close they were to villages, so that hearings could be conducted based on real-time elephant movement.“Ten additional centres have been set up in the district, including a consolidated venue catering to villages from two assembly constituencies in elephant corridors,” said Bijin Krishna, the DM of West Midnapore.

In Jhargram, special hearing centres have been established at 10 high schools across the Nayagram, Gopiballavpur, Jhargram and Binpur constituencies. The DM, Akanksha Bhaskar, said the measures were taken in the interest of public safety.Where work is proofIn the North Bengal districts of Darjeeling, Kalimpong, Jalpaiguri, Cooch Behar, Alipurduar, North Dinajpur and South Dinajpur, employment records issued by tea gardens and cinchona plantations are valid proofs of identity and residence for workers and their families.Labourers in tea and cinchona estates — many of whom have lived in makeshift quarters for generations — have struggled to produce conventional documents, such as land records or formal proof of address.

As a result, during SIR hearings, they have been unable to come up with those documents, leading to fears of disenfranchisement. Plantation employment records are routinely maintained by garden authorities, and now that they have been recognised by the commission as a bona fide voter eligibility document, it’s come as immense relief for workers.Netas across the political spectrum welcomed the move, but while BJP MP Jayanta Roy called it an “excellent step”, TMC’s Rajya Sabha MP, Prakash Chik Baraik, said the move ought to have been taken long ago, and that the delay had caused unnecessary panic.Special sessions for vulnerable tribal groups & sex workersMembers of Particularly Vulnerable Tribal Groups (PVTGs) have welcomed EC’s decision to conduct doorstep verification, amid concerns over document availability and identity mismatch.In Totopara, home to the Toto community (the state’s smallest PVTG) in North Bengal’s Alipurduar, residents said the move has eased anxieties over land and identity records. “Many families do not have land khatiyans, while migrant workers lack links to ancestral property. We were worried, but the EC has taken extra care,” said Bakul Toto, secretary of the Toto Kalyan Samiti.

Similar issues have surfaced among the Birhor and Lodha Shabar communities.

Around 300 Birhors live in south Bengal’s Purulia district — across Balarampur, Baghmundi and Jhalda-I blocks, with 181 adults listed in the 2024 Lok Sabha electoral rolls. In forest-dependent areas, many Birhor families now reside in permanent houses provided by the state, but discrepancies in records have triggered SIR hearings.Lodha Shabar members — spread across West Midnapore and Jhargram — are also receiving notices.

The community comprises over 1 lakh people across nearly 17,000 families. District administrations had flagged concerns over whether members possessed sufficient documentation, following which the EC, on Dec 31 last year, instructed DEOs to conduct physical verification.In West Midnapore, Lodha Shabar residents have been attending hearings at block development offices. In the Keshiary block, multiple villagers were summoned despite having submitted details during the enumeration.

“We produced voter ID, Aadhaar and family details at the hearing,” said Basanti Dandapat of Lengamara village.West Bengal Lodha Shabar Development Board chairman Balai Naik said teams were visiting villages to reassure residents. “There is no need to panic. In cases of spelling errors or linkage issues, officials will verify details on the ground,” he said.Similar “special public hearings” have been ordered for sex workers as well, as many of them lack identity proof.Officials said district election officers have been instructed to hear such cases separately and adopt a facilitative approach, recognising that many sex workers have been disconnected from their families for decades or do not know their parents’ names.For 55-year-old Baby Khatun, who has lived in Sonagachi, Kolkata’s largest red light district, since she arrived there at the age of 10, the hearing notice triggered panic.

“I only remember that my family lived in Kidderpore. I don’t know my parents’ names,” she said. With no immediate relatives, she listed her landlord as her guardian. “How can I produce a family tree? I don’t even know their names. I’m afraid my name will be deleted,” she said.Rekha Das, another sex worker, has a voter and Aadhaar cards but faced difficulty enrolling her son, a first-time voter, because the form requires the name of a blood relative from the mother’s side. “I have documents, but no family records,” she said.EC officials said the concerns were genuine and assured no eligible voter would be struck off the rolls solely for lack of documents, stressing that SIR was aimed at inclusion, not exclusion.- Tamaghna Banerjee, Sujoy Khanra, Pinak Priya Bhattacharya, Sudipto Das, Poulami Roy Banerjee & Tanuja Singh Deo

1 hour ago

4

1 hour ago

4

English (US) ·

English (US) ·