ARTICLE AD BOX

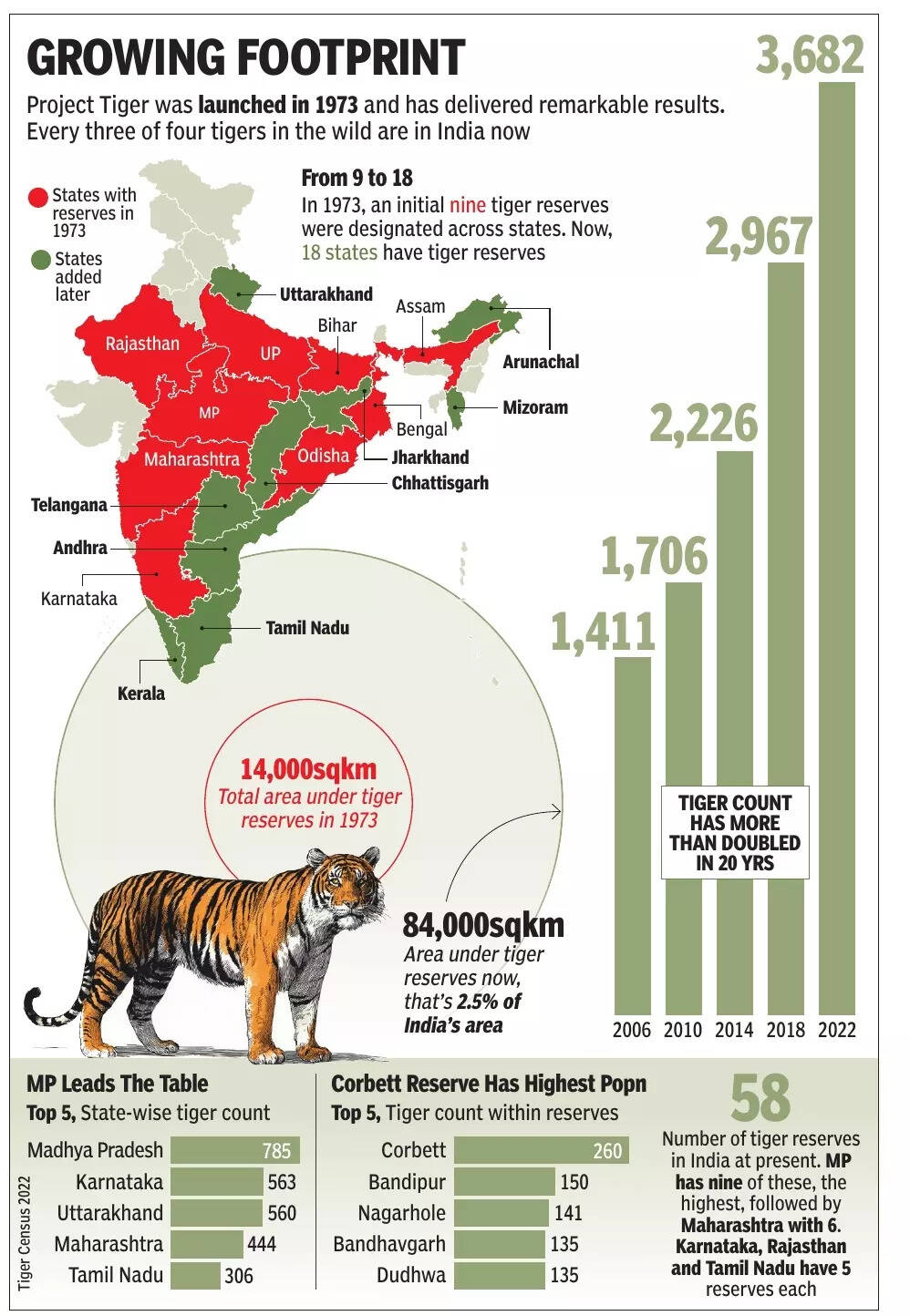

NEW DELHI: In 2006, India had just 1,411 tigers left in the wild. By 2022, there were 3,682, almost 75% of the world’s wild tiger population — a 161% jump in just 16 years.More than 50 years since the launch of Project Tiger in 1973, the numbers tell a tale that’s obvious: tiger conservation has been a roaring success.

But challenges remain.

Where Tigers Get Caught Between Faith And Tourism | I Witness

The numbers are significant, especially in the backdrop of a decline in tiger population in the 1980s, and a period of not-so-robust growth thereafter because of multiple factors, primarily poaching. By 2004, the situation had become so bad that tigers were on the brink of extinction at Rajasthan’s Sariska Tiger Reserve. The country’s wildlife managers and biologists sensed the urgency and started taking multiple measures to protect the existing tiger population and increase the number of big cats.But, in the journey from 1,411 in 2006 to 3,682 in 2022, many lessons have been learnt — primarily about human-tiger conflict and the lurking threat of poaching.

“The country has been a leader in tiger conservation,” said Yadvendradev V Jhala, a senior scientist at Tata Institute of Fundamental Research, and a former dean of Wildlife Institute of India (WII). But Jhala — who has been part of the journey to bring back tigers through policy intervention and management strategies, following the Sariska situation — cautions that the threat to tigers has never gone away.

“Though India now has approximately 3,700 tigers, they are still vulnerable and can be decimated if poaching is left unchecked, as the market for illegal tiger parts and products still thrives outside India.

”He also reminded that the tiger population increase had not been uniform: reserves such as Palamau (Jharkhand), Achanakmar (Chhattisgarh), Satkosia (Odisha), Dampa (Mizoram) and Buxa (Bengal) have seen declines and localised extinctions.On the other hand, big cat populations in Uttarakhand and eastern Maharashtra had increased so much that man-animal conflict has become an issue. “Also, Chhattisgarh, Odisha and Jharkhand have registered declines, though they have good habitats because of prey base depletion,” Jhala said.India began its efforts to protect the tiger population when it launched Project Tiger as a centrally sponsored scheme in 1973 in nine reserves (Assam, Bihar, Karnataka, Madhya Pradesh, Maharashtra, Odisha, Rajasthan, Uttar Pradesh and Bengal) over a 14,000sq km area.

Since then, project coverage has expanded to 58 tiger reserves, over more than 84,487sq km across 18 states, occupying nearly 2.5% of the country’s total geographical area.The numbers show that approximately 35% of our tiger reserves urgently require enhanced protection measures, such as habitat restoration, ungulate augmentation and subsequent tiger reintroduction.“Tiger recovery is linked with rural community prosperity and law and order,” Jhala said.

“In the last 20 years, wherever there has been extreme poverty and armed conflicts (Maoist activity or other law-and-order problems), we have seen tiger extinctions. Improving the livelihoods of forest communities, so that they do not have to rely on forest produce for a living, will reduce their negative impact on biodiversity.

”He, however, stressed that India would need a strategy to manage the growing population of tigers.

“If this is not done in time, there will likely be a severe backlash from local communities, and we stand to lose all we gained in the past 20 years.”The conflict has, indeed, taken a human toll. The environment ministry told Parliament on July 24 that 73 lives were lost in tiger attacks in 2024, with Maharashtra reporting the highest (42), followed by UP (10), MP (6), Uttarakhand (5) and Assam (4). There were 51 human lives lost in 2020, 59 in 2021, 110 in 2022 and 85 in 2023.Indian Forest Service officer and Barabanki DFO Akash Deep Badhawan said during his tenure as DFO Katarniaghat Wildlife Sanctuary, Dudhwa Tiger Reserve, Bahraich, forest personnel grappled with a mix of threats: a 45km porous border with Nepal, with cross-border gangs and illegal wildlife trade putting staff at risk. Understaffing and resource shortages are another constraint. “Human-wildlife conflict fuels mistrust between communities and enforcement teams.

Efforts to evict encroachments or set up fencing provoke resistance from villagers, compounding socio-political tension. Balancing legal constraints, regulatory delays, and ecological imperatives adds further administrative and ethical complexity.”

.png)

.png)

.png)

3 hours ago

4

3 hours ago

4

English (US) ·

English (US) ·