ARTICLE AD BOX

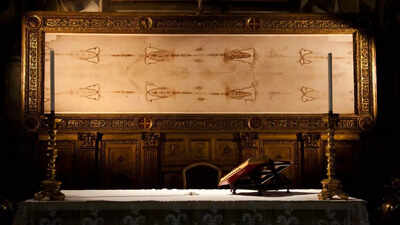

Fresh debate over the Shroud of Turin has erupted in the pages of the peer-reviewed journal Archaeometry, where three researchers are pushing back against a recent claim that the relic is a medieval forgery.The renewed clash follows a study published last summer by Brazilian 3D designer and researcher Cicero Moraes. In that paper, Moraes used digital modeling to test how linen would drape over two different forms: a real human body and a shallow carved relief laid on a flat surface. He concluded that the proportions and distortions visible on the Shroud aligned more closely with a shallow bas-relief template than with a body wrapped in cloth.But in a newly published response in Archaeometry, Shroud specialists Tristan Casabianca, Emanuela Marinelli and Alessandro Piana argue that Moraes’ reconstruction contains critical weaknesses and fails to account for key physical characteristics of the cloth itself.The Shroud, preserved in Turin’s Cathedral of St John the Baptist, measures roughly 14.5 feet by 3.7 feet. It bears the faint front-and-back image of a man marked with wounds consistent with crucifixion.

Since it first appeared in France in the 14th century, the linen has been venerated by many Christians as the burial cloth of Jesus. Others have questioned its authenticity for just as long.In 1989, radiocarbon testing dated the cloth to between 1260 and 1390 CE, placing it squarely in the medieval period. Later researchers challenged those findings, arguing that the tested material may have come from a repaired section of the fabric rather than the original weave.Moraes’ more recent study did not revisit carbon dating. Instead, it focused on image formation. By simulating how fabric would conform to different surfaces, he proposed that the Shroud’s image could have been created by draping linen over a shallow relief—possibly made of wood, stone or metal, designed to transfer the figure.Casabianca, Marinelli and Piana counter that this approach overlooks two central features of the Shroud.

They write that the image exists only at a surface level, affecting the outermost fibers, and that separate analyses have identified what they describe as real blood on the cloth. According to them, these elements complicate the idea of a medieval artisan fabricating the relic using a carved template.They also challenge the historical framework underpinning the forgery theory. Moraes cited historian William Dale, who argued that the Shroud’s style appears Byzantine.

But the responding scholars note that such an aesthetic would predate and geographically diverge from 14th-century France, where the Shroud first surfaced. They argue that this weakens the suggestion that a medieval French craftsman conceived and executed the image, particularly one depicting a nude, front-and-back, post-crucifixion Christ, a motif they say was virtually absent from Western medieval art.Moraes has replied in Archaeometry, defending his methodology. He described his work as “strictly methodological,” stressing that his focus was on how human forms transfer onto fabric rather than on theology or devotional claims. He also pointed to four artworks from the 11th to 14th centuries as possible visual precedents, though his critics maintain that none replicate the Shroud’s distinctive composition.Outside the academic exchange, church officials have urged caution. Cardinal Roberto Repole, Archbishop of Turin and custodian of the Shroud, warned last year against what he called “superficial” conclusions and called for deeper scientific scrutiny.

6 days ago

6

6 days ago

6

English (US) ·

English (US) ·