ARTICLE AD BOX

Jupiter is slightly smaller than scientists believed for decades: NASA’s Juno mission finally explains why (Image Source - NASA)

Jupiter has long been described as a swollen, fast-spinning giant, but its exact dimensions have rested on ageing measurements. For decades, scientists relied on radio signals gathered briefly by Voyager and Pioneer spacecraft in the late 1970s.

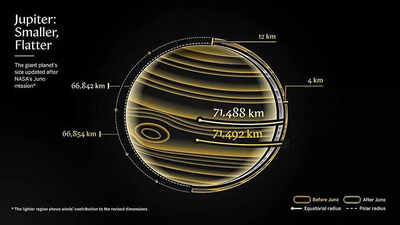

Those figures shaped textbooks, models and even how astronomers judge planets beyond the Solar System. Now, a new analysis based on far richer data from NASA’s Juno mission offers a quieter but important correction. By using dozens of modern radio occultation measurements and factoring in Jupiter’s powerful winds, researchers have narrowed the uncertainty dramatically. The planet is still enormous and visibly flattened, but it is slightly smaller than once thought.

The change is modest in kilometres, yet meaningful for how Jupiter is understood and used as a reference world.

NASA’s Juno mission redefines size and shape of Jupiter

Juno has spent recent years looping close to Jupiter, sending radio signals through the planet’s atmosphere back to Earth. As those signals bend and slow, they reveal the planet’s shape at specific pressure levels. Compared with the six usable profiles from earlier missions, Juno has delivered more than twenty high-quality measurements.

This dense coverage allows scientists to match observed radii to physical models with far less guesswork.

The result is a reduction in uncertainty from around four kilometres to less than half a kilometre.

Jupiter's equatorial bulge confirmed but slightly reduced

The new figures confirm that Jupiter’s equator bulges strongly due to its rapid rotation of just under ten hours. At the one-bar pressure level, close to the visible cloud tops, the equatorial radius is now placed at about 71,488 kilometres.

The polar radius comes in at roughly 66,842 kilometres. Both values are smaller than the long-accepted numbers, by four kilometres at the equator and twelve at the poles. The difference is subtle on a planetary scale, but it shifts the mean radius downward as well.

Atmospheric winds shape the planet more than once assumed

Earlier studies treated Jupiter largely as a smooth rotating body. The new work takes its fierce east-west winds into account. These winds add extra centrifugal force, altering the planet’s outline by several kilometres, especially near low latitudes.

Juno’s data suggest that winds above the cloud deck change little with height up to around the 100-millibar level. This near-barotropic behaviour simplifies how the atmosphere couples to the interior and explains why the wind-corrected shape fits the data so closely.

The revised shape helps reconcile interior models

A slightly smaller Jupiter has knock-on effects below the clouds. Interior models that struggled to match temperature readings from the Galileo probe now find more room for a cooler and more metal-rich outer layer.

The revised shape eases long-standing tension between different datasets rather than creating new ones. It also improves how gravity and pressure measurements are mapped onto real depths inside the planet.

Jupiter remains a key benchmark for giant planets

Jupiter is often used as a yardstick, not just in the Solar System but when studying gas giants orbiting other stars. A more accurate radius feeds directly into those comparisons. As Juno continues and future missions like Juice extend coverage, the picture may sharpen further. For now, the adjustment is small, careful and grounded in better data. Jupiter has not changed, but our sense of its outline has settled into a clearer shape

12 hours ago

4

12 hours ago

4

English (US) ·

English (US) ·