ARTICLE AD BOX

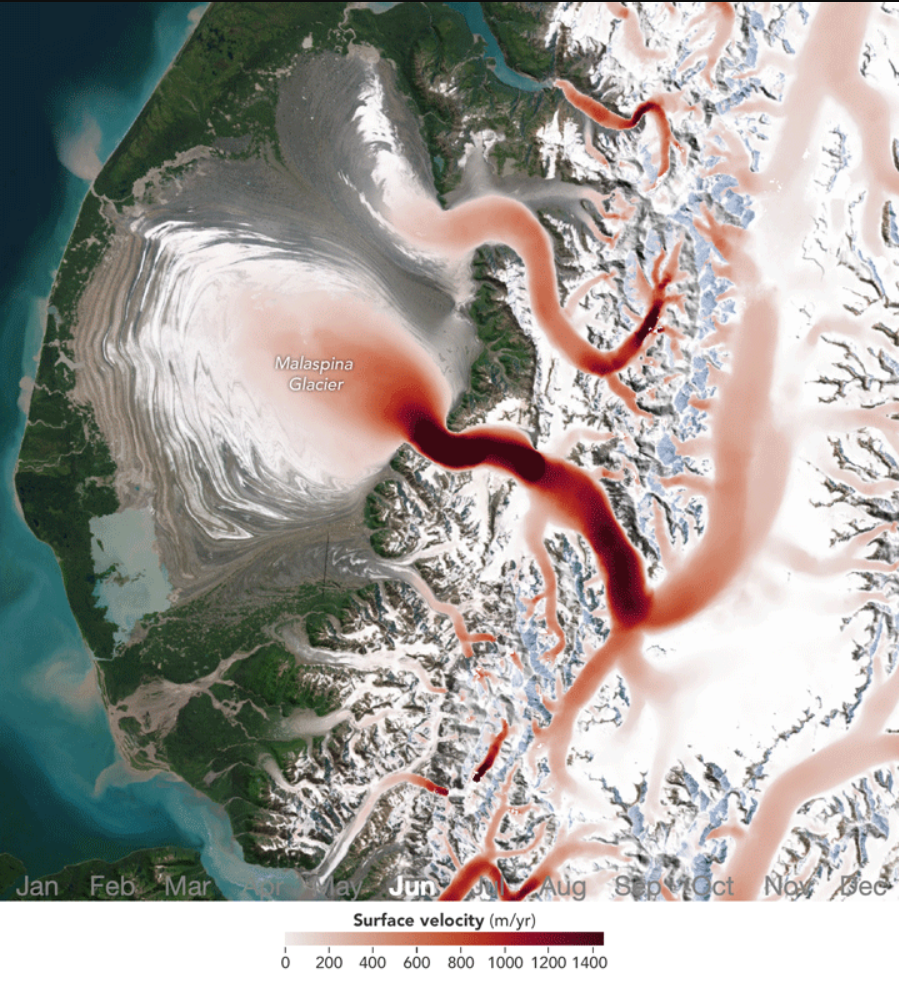

NASA maps how Earth’s glaciers speed up and slow down through the year

Glaciers have never been still. They move again and again often in step with the seasons. Scientists have known this for a long time, mostly by watching individual glaciers or small regions.

What has been harder to see is how this behaviour plays out across the whole planet. A study published in Science in November 2025 offers that wider view. Using more than 36 million pairs of satellite images, researchers have assembled the first global record of how glacier speeds rise and fall through the year. Much of the data comes from the long-running Landsat programme. The picture that emerges is uneven but clear enough.

As the climate warms, seasonal swings in glacier motion are becoming more pronounced, especially where yearly temperatures now pass the freezing point.

A NASA study tracks global glacier flow through the seasons for the first time

The analysis builds on the ITS_LIVE ice velocity dataset developed at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory. It draws together imagery from Landsat missions stretching back decades, alongside data from Europe’s Sentinel satellites. This long view matters. Landsat’s stable orbits and consistent geometry mean the same places can be revisited again and again, often under similar conditions.

Subtle shifts on glacier surfaces, barely visible in a single image, become measurable when stacked over time.

Older data does not fade into the background. It still carries weight next to newer, sharper observations.

A NASA study tracks global glacier flow through the seasons for the first time (Image Source - NASA)

Warmer conditions bring stronger seasonal changes

When the researchers stepped back and looked across regions, a simple relationship appeared. Seasonal changes in glacier speed tend to show up once annual maximum temperatures climb above zero degrees Celsius.

From there, the signal grows stronger with each degree of warming. Many glaciers now speed up more clearly in summer and slow more noticeably in winter. This pattern stands out in temperate and coastal areas.

In colder polar regions, the seasonal rhythm is often weaker, sometimes barely visible.

Fine surface details make movement measurable

Tracking glacier flow depends on following surface features from one image to the next. This feature tracking works best when the imagery is sharp.

For recent Landsat missions, the 15 metre panchromatic band provides enough detail to lock onto crevasses and surface texture. For older Landsat 4 and 5 images, the visible red band offered the best contrast over bright ice. The movements involved can be small, but over weeks and months, they add up.

Radar fills gaps left by optical imagery

Optical satellites need daylight and clear skies. Radar does not. Radar images can be taken through clouds and during the polar night, filling gaps in winter records.

Yet radar has limits of its own. When snow and ice become wet during melt seasons, surface features blur. By combining radar and optical data, the team pieced together more continuous records. Radar also helped estimate uncertainty by checking for false motion over solid ground that should not move at all.

Local landscapes still matter

Despite the global scale, the study does not flatten everything into one story. Glaciers respond to their surroundings.

Bedrock type, meltwater pathways and fjord shape all influence how ice moves. A glacier flowing into the sea behaves differently from one ending on land. This is why results from one place rarely transfer neatly to another. The strength of this dataset lies in showing broad patterns while leaving room for local detail.The researchers see the work as a beginning rather than an endpoint. Landsat 9 data is already being added, and more questions sit within the record than answers. Much of what glaciers are doing season by season is now visible but not yet fully understood. The motion is there, quietly traced across the ice.

8 hours ago

5

8 hours ago

5

English (US) ·

English (US) ·