ARTICLE AD BOX

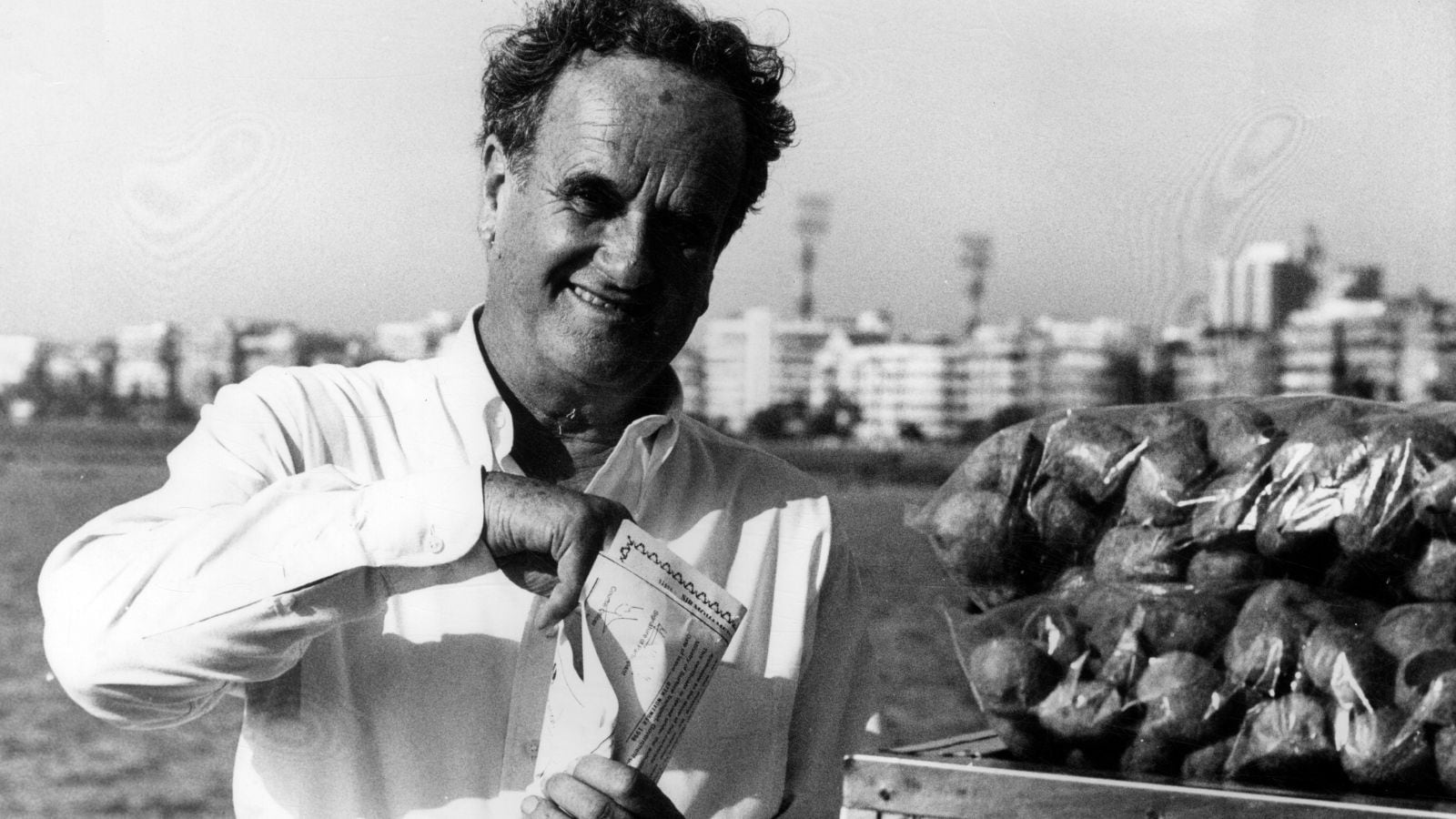

Veteran BBC journalist Sir Mark Tully, revered as the ‘voice of India’, died in New Delhi at the age of 90 after spending most of his life reporting from the country he called home. (Express Archive Photo)

Veteran BBC journalist Sir Mark Tully, revered as the ‘voice of India’, died in New Delhi at the age of 90 after spending most of his life reporting from the country he called home. (Express Archive Photo)

Sir Mark Tully, the broadcaster whose warm voice that once travelled through crackling shortwave radios to become, for millions, the most trusted interpreter of India, passed away in New Delhi at the age of 90. For nearly three decades, Tully was not merely the BBC’s South Asia correspondent; he was, as colleagues and listeners alike called him, the “voice of India” .

Born in Calcutta in 1935, a child of the British Raj, Tully’s relationship with India was neither transient nor detached. “It was his home,” historian William Dalrymple said. “There was never any question that he would retire to England. He wanted to remain in India and to die here — which is what he’s done,” he added. Raised partly in India and later educated in Britain, Tully returned in 1965 with the BBC, initially in an administrative role, before growing into one of the most influential foreign correspondents the country has known.

His reporting spanned the most turbulent chapters of South Asia’s modern history: the Emergency of 1975, after which he was expelled from India; the Bhopal gas tragedy; Operation Blue Star and the storming of the Golden Temple; the assassination of Indira Gandhi and later Rajiv Gandhi; and the demolition of the Babri Masjid in 1992, where he narrowly escaped lynching as mobs chanted “Death to Mark Tully”, a moment, he later said marked “the gravest setback” to Indian secularism since Independence.

Former BBC journalist Qurban Ali remembered Tully’s method as uncompromisingly independent. “He never became an embedded journalist,” Ali said. “He preferred to close the office and leave rather than report what the government of the day wanted.” His commitment to institutional integrity eventually put him at odds with the BBC itself. In 1993, he publicly accused Director General John Birt of running the organisation by “fear,” a confrontation that preceded his resignation the following year .

Author, translator and literary historian, Rakhshanda Jalil, recalled the singular credibility Tully commanded in rural north India. “In eastern Uttar Pradesh, people would say, ‘Tully sahab ne kaha hai, sahi hoga’ (If Mr Tully has said it, it must be true)’,” she said. “That was the ring of authenticity his reporting carried.” She attributed this trust to “his completely non-judgmental attitude towards India and Indians.” That non-judgmental empathy was forged on the ground. Tully travelled relentlessly, preferring trains, village conversations, and long cups of chai to official briefings. “Here was somebody who actually travelled the ground. He belonged to a generation who sat down with people and listened. That ear to the ground is something journalism is losing,” Jalil added.

Historian S Irfan Habib, who met Tully frequently at the India International Centre, recalled how insistently he embraced the language. “He always said, ‘Irfan, we will talk in Hindustani’. He wanted to brush up his Hindi,” Habib said, adding that Tully especially loved the dialect and usage of language of western Uttar Pradesh.

Former broadcaster and ex India Habitat Centre director Sumit Tandon remembered another side of Tully . “He had a wonderful sense of humour and a very acute understanding of Indian society,” he said. Tully’s long-running BBC Radio 4 programme Something Understood revealed that dimension – reflective, philosophical and spiritually curious. “Those were beautiful programmes,” Tandon said, “dealing with poetry, music and philosophy. They showed his intellectual and spiritual side.” Importantly, Tandon added, “he could criticise without being unkind — an art that is lost nowadays.”

Story continues below this ad

Alongside broadcasting, Tully built a substantial literary legacy. He authored nine books, including Amritsar: Mrs Gandhi’s Last Battle, No Full Stops in India, India in Slow Motion, and Upcountry Tales works that reflected his deep engagement with rural north India and the moral complexities of the country he loved.

Knighted in Britain and honoured with both the Padma Shri and Padma Bhushan, he lived quietly in Nizamuddin, with his partner, journalist Gillian Wright.

Ratish Nanda, CEO, Aga Khan Trust for Culture,

who us instrumental in restoring Humayun’s Tomb and the Sunder Nursery in Delhi, encountered Tully almost every day at the Sunder Nursery during the pandemic. “I really got to know Mark and Gillian during the pandemic when they began to spend much of their day along with their dogs at the Sunder Nursery park. Over the past six years, whenever he was well, Mark would be found in the park enjoying – nature, birds and visitors.” He added, “Always smiling, humble, polite, kind, appreciative and generous. We will find a way to keep his memory alive.”

English (US) ·

English (US) ·