ARTICLE AD BOX

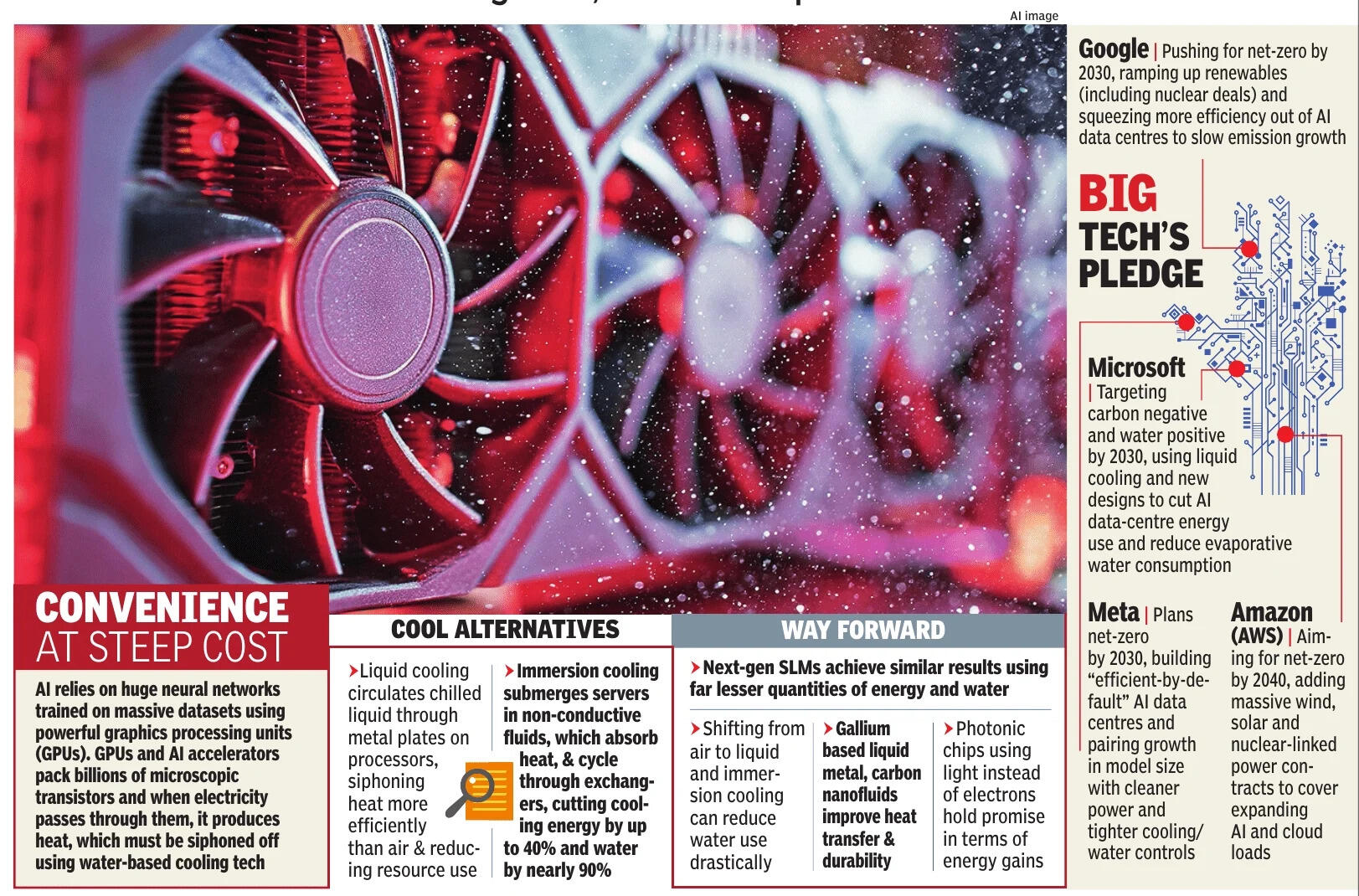

Artificial intelligence is easily the most deceptive technological innovation of the 21st century. Its ease of use and the lightning-fast reflexes with which it spits out responses belie its enormous appetite for water and energy.ChatGPT took the world by storm when it launched in late 2023, signalling an era of intelligence demand marked by seamless, conversational interactions between user and machine But behind every smooth exchange lies a complex physical process. Modern AI is built on vast neural networks trained on trillions of words, images, and numbers. This training, to help models learn to predict the next word or recognise a pattern, involves processing colossal datasets repeatedly through graphics processing units, or GPUs.

These chips, originally designed for rendering video game graphics, have become AI workhorses because they can perform thousands of mathematical operations simultaneously.

But this speed comes at a price: intense heat.

Every watt of electricity that powers a GPU becomes heat that must be removed to prevent the hardware from failing. That is why AI facilities, especially those training large language models (LLMs), rely on intricate cooling systems.

It is simple thermodynamics. Moving heat away requires energy, and if the cooling is water-based, it requires water too. The hotter the chips run, the more resources they draw.Sample this: a typical ChatGPT query consumes 0.32 ml of water. Multiply this by billions of queries per day, and the amount of water used to power daily AI interactions is staggering.Data centres use evaporative cooling, where air is blown through watersoaked pads or towers to remove heat, leading to substantial water loss through evaporation.

But as water scarcity grows, operators are experimenting with alternatives. “Emerging technologies such as liquid and immersion cooling are promising. Waste-heat recovery and reuse for nearby industrial or agricultural applications can add value to this by-product,” says Deborshi Barat, head of public policy and knowledge management at S&R Associates.

“Shifting from evaporative to air-based cooling, and locating data centres in less water-scarce regions” could be ways to reduce the water footprint, he adds.The near constant introduction of new AI models only adds to the problem. The higher the number of LLMs, the greater the need for resources to run those models. Massachusetts Institute of Technology researchers estimate that training an LLM consumes several million litres of fresh water. The International Energy Agency projects that AI data centres could account for 8% of global power demand by 2030.Rather than an infrastructure overhaul, experts suggest incremental steps.

“Small language models produce similar or sometimes better accuracy, but [are] not significant in terms of energy or water consumption,” says Sushant Singh from International Institute for Sustainable Development.There are steps that can be taken, even with the software, that can help. According to Barat, model compression and carbon-aware scheduling of AI systems can reduce computational load and energy draw.Singh feels regulation of AI use will go a long way. “Every enterprise wants its own LLM. Custom LLMs reuse parts of existing ones, consuming more energy and water. Regulation could create checks and balances — limiting model size or token count,” Singh says. “Realistically, energy use can’t be reduced completely, but we can at least ensure it’s clean. Requiring data centres to use only renewable or non-polluting energy (nuclear, solar, or hydro) could help.

”

1 week ago

7

1 week ago

7

English (US) ·

English (US) ·