ARTICLE AD BOX

Thomas Stoltz Harvey pictured in 1994 holding part of Einstein's brain which he'd kept with him for decades (Michael Brennan/Getty Images)

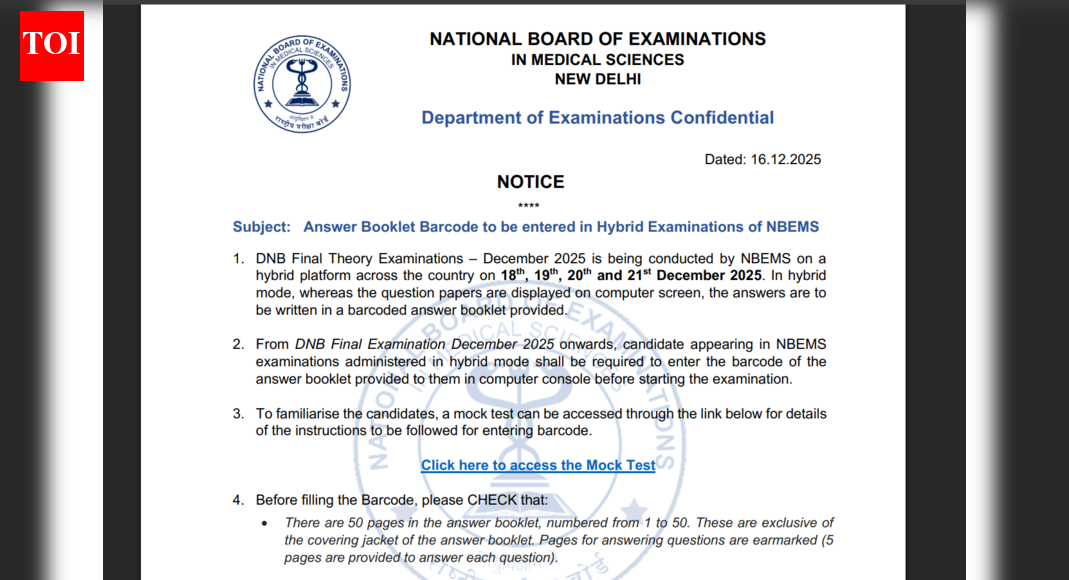

Albert Einstein died on 18 April 1955, aged 76. His death marked the end of one of the most influential scientific lives in history. It also marked the beginning of a long, unsettled afterlife for his brain. Einstein was admitted to Princeton Hospital the previous evening, complaining of chest pain. In the early hours of the morning, he died from a ruptured abdominal aortic aneurysm. He had declined surgery, reportedly telling doctors he wanted to go “when I want to go,” and not prolong life artificially. His instructions for what should follow were clear: his body was to be cremated, and his ashes scattered in secret, specifically to avoid the creation of shrines or symbols that might turn him into an object of public reverence. What happened next violated both the spirit and, initially, the letter of those wishes. The autopsy was carried out by Dr Thomas Stoltz Harvey, the chief pathologist on duty at Princeton Hospital. Harvey was not a neurologist or brain specialist. His professional expertise lay in general pathology, identifying disease, injury, and cause of death, not in the study of cognition or intelligence. Yet during the autopsy, Harvey removed Einstein’s brain and kept it.

At the time, he did not have permission from Einstein’s family to do so. In later interviews, Harvey offered varying explanations. He said he “assumed” permission had been granted. He said he believed the brain would be studied for science. He said he felt an obligation to preserve it. What is clear, based on contemporary reporting and later historical work, is that no explicit consent existed when the brain was removed. Only days later did Harvey seek retroactive approval from Einstein’s eldest son, Hans Albert Einstein. That approval was reluctant and conditional. Hans Albert agreed only on the understanding that any research would be conducted strictly in the interests of science, and that any findings would be published in reputable scientific journals. By then, the damage to Einstein’s stated wishes had already been done. Harvey did not stop with the brain. He also reportedly removed Einstein’s eyeballs, later giving them to Henry Abrams, Einstein’s ophthalmologist. Those eyes remain in a safe deposit box in New York, a detail that has become part of the unsettling mythology surrounding Einstein’s remains. Within months of the autopsy, Harvey was dismissed from Princeton Hospital. His refusal to surrender the brain to the institution played a decisive role.

While Hans Albert Einstein had accepted Harvey’s assurances, the hospital’s director did not. Harvey left Princeton carrying Einstein’s brain with him, quite literally, as his professional standing began to unravel. What followed was not a controlled scientific programme, but decades of improvised custody. Harvey photographed the brain, weighed it, and cut it into approximately 240 sections. He preserved the pieces in jars and created microscope slides, 12 sets, according to later accounts, labelled and stored without any institutional oversight.

Some samples were sent to researchers; most remained with Harvey. At various points, the brain travelled with him as he moved between jobs and cities, reportedly stored in containers ranging from laboratory jars to a beer cooler. For years, little was published.The first significant study based on Einstein’s brain did not appear until 1985, three decades after his death. Led by neuroscientist Marian Diamond, it reported an unusual ratio of neurons to glial cells, the support cells that nourish neurons and regulate their chemical environment, in certain regions of the cortex.

The suggestion was that this cellular balance might relate to enhanced cognitive capacity.Media coverage at the time was breathless, with headlines implying that scientists had uncovered the neural secret behind E = mc². Within the scientific community, however, the response was restrained. Critics argued that conclusions drawn from a single brain, without robust control samples or consistent methodology, could not meaningfully explain intelligence.“You can’t take just one brain of someone who is different from everyone else, and we pretty much all are, and say, ‘Ah-ha, I’ve found the thing,’” said Terence Hines, a psychologist at Pace University, who has been a long-standing critic of the Einstein brain studies. Comparing the logic to attributing stamp collecting to a single brain feature, he dismissed such claims as “bull”.Subsequent examinations did identify other anatomical differences.

A 2013 study co-authored by anthropologist Dean Falk reported that Einstein’s corpus callosum, the bundle of fibres connecting the brain’s left and right hemispheres, was thicker in certain regions than in control groups, suggesting greater inter-hemispheric communication. Falk also noted structural variations in Einstein’s frontal and parietal lobes, including an additional ridge in the mid-frontal area associated with planning and working memory, and asymmetry in the parietal regions linked to spatial reasoning.

Image: BBC

`Another frequently cited feature was a pronounced “omega sign” on the right motor cortex, a trait sometimes observed in left-handed musicians. Einstein played the violin throughout his life.Even so, researchers have consistently cautioned against drawing direct causal links between these anatomical traits and genius. No two human brains are identical, and many of the features highlighted in Einstein’s case fall within the broad range of normal variation.

As Harvey himself acknowledged in 1978, all research conducted up to that point showed Einstein’s brain to be “within normal limits for a man his age,” a finding he did not rush to publish. Over time, the story shifted from neuroscience to cultural oddity. In 1978, journalist Steven Levy tracked Harvey down in Wichita, Kansas, after discovering the brain was missing from Princeton Hospital. When Levy asked to see photographs, Harvey instead opened a cooler containing jars of tissue.

The moment reignited public fascination and renewed scrutiny of Harvey’s actions.In Postcards from the Brain Museum by Brian Burrell and Finding Einstein’s Brain by Frederick Lepore, the episode is reconstructed through archival records, interviews, and decades of reporting on Thomas Harvey’s custody of the brain. Harvey lived until 2007, dying at the age of 94. By that point, portions of Einstein’s brain had been transferred out of private possession and into public institutions.

The Mütter Museum in Philadelphia received 46 sections, while additional fragments were sent to the National Museum of Health and Medicine, bringing an end to the brain’s decades-long journey outside formal collections. Nothing resembling Harvey’s original ambition ever materialised. No secret of genius was unlocked. No definitive biological explanation emerged. What remains is a strange historical footnote: that one of the greatest minds of the modern era spent four decades divided into jars, studied sporadically, debated endlessly, and ultimately taught us far more about our obsession with genius than about genius itself.

5 hours ago

3

5 hours ago

3

English (US) ·

English (US) ·