ARTICLE AD BOX

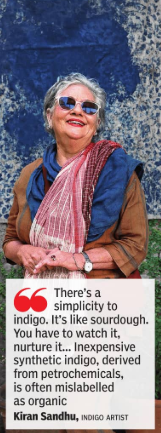

DEHRADUN: It’s not hard to guess Kiran Sandhu’s favourite colour. Blue streaks the silver curls crowning the veteran artist, stains the palms of the women working on her farm in Uttarakhand and flows through fabrics that hang from clotheslines like rivers.Turquoise, cobalt, teal… an indigo spectrum greets visitors near her home in Rudrapur, where she has spent nearly three decades coaxing blue pigment from her green indigo crops in the monsoon-fed plains of Terai.

In an age of AI-powered automation, Sandhu’s textile landscapes — four of which are on display at the Art of India (AOI) exhibition in Delhi, and soon in Jaipur and Mumbai — reinforce the value of labour and patience.Once old sheets and curtains, these ‘Landscapes Of Indigo’ have been transformed into canvases over eight to ten years of careful harvests. Sandhu filtered the liquid dye through recycled household linens which, over time, have absorbed the passage of indigo — its drip and bloom. The resulting patterns evoke rivers, storms and skies.“People think the process is dramatic and complicated,” she says. “But it’s simple.

Like sourdough. You have to watch it, nurture it, adjust it when needed,” says Kiran, the owner of Tarai Blue, a farm-to-fabric enterprise focused on natural indigo dyeing and sustainable textiles.Blue dominated the landscape of her childhood in Gorakhpur, UP, where Rajera indigo bungalows dotted her family’s sugarcane estate. Blue was also the colour of her mother’s eyes, a presence she continues to carry in every vat and fabric.Sandhu’s mother introduced her to a bouquet of natural materials and shades. This led her to study textile design. When she and her classmates struggled to source natural indigo, a casual suggestion to grow it themselves changed everything. Sandhu acquired a few grams of organic seeds and began learning online, through workshops, and eventually from agricultural experts. In the fields around her in Uttarakhand today, wheat, rice, and sugarcane grow alongside her Indigofera tinctoria, the crop she calls Tarai Blue.Yet the taint of history remains stubborn. Indigo’s legacy under British rule was steeped in blood. Colonial planters coerced Indian farmers into growing indigo instead of food crops, trapping them in cycles of debt. Resistance erupted in the Indigo Revolt of 1859–60, when peasants across Bengal refused to sow the plant. “Indigo has such a dark background that people think the plant itself is bad,” says Sandhu.While her ancestral home in eastern UP still stands on land once cultivated by indigo farmers, Sandhu, alongside her husband, built their home in Rudrapur, a region shaped by successive waves of migration after Partition.

“This place was a jungle when we moved here,” she recalls, describing her mission to reclaim indigo’s purity in the Terai. “Indigo is actually a legume. It’s good for the soil.”The fertile soil, monsoon-fed climate, and tall grasslands of the Terai proved ideal for her work. “Indigo loves hot, steamy weather. So, this place was perfect,” she says. Indigo, she explains, is not blue inside the plant. Fresh leaves contain indican, which transforms through fermentation into the insoluble blue pigment, indigotin.

The liquid shifts from greenish yellow to blue before the pigment settles, is filtered, pressed, and dried into cakes.

Fabric dipped into the vat slowly turns from green to blue as it oxidises in air.The “magic and mystery” of indigo, she says, is that weather, temperature, and timing shape every outcome. Today, her farm-to-fabric studio produces naturally dyed garments in “every colour under the sun” and collaborates on custom projects.

The Tarai Blue pigment is now used on textiles, wood, stoneware, and architectural surfaces. “Indigo is a difficult colour to use as paint,” she says.The stakes are ecological as much as aesthetic. Around 280,000 tonnes of chemical dyes enter the oceans every year. “Inexpensive synthetic indigo, derived from petrochemicals, is often mislabelled as organic,” says Sandhu.Overseas visitors often join village women in dipping fabric into giant blue drums and watch them sew and knit at her studio. What the artist hopes visitors take away from AOI is “a sense that the ancient colour is alive” and that with time and care, even green can turn blue.

1 hour ago

2

1 hour ago

2

English (US) ·

English (US) ·