ARTICLE AD BOX

The Congress party is experiencing a steady erosion of internal authority, leading to a continuous exodus of legislators across all levels

When twelve Congress councillors in Maharashtra’s Ambernath were suspended for “anti-party activities” and they walked straight into BJP fold within a day, the episode felt shocking only on the surface.

In reality, it was merely the latest chapter in a long, evolving story of Indian politics—one where party loyalty has steadily given way to political survival, and where elections increasingly decide who enters the arena, not necessarily who governs.The numbers tell a blunt story. Between 1999 and 2009, Congress won between 114 and 206 Lok Sabha seats, peaking in 2009 with a strong mandate. In 2014, its tally collapsed to 44 seats, recovering marginally to 52 in 2019 and about 99 in 2024. Electoral decline alone does not explain the present crisis. What distinguishes this phase is the steady erosion of the party’s internal authority, producing a conveyor belt of exits cutting across regions, castes, generations, and ideological leanings.The phenomenon cuts across levels of governance: local bodies, state assemblies, Parliament. It spans ideologies, caste groups, generations, and regions.

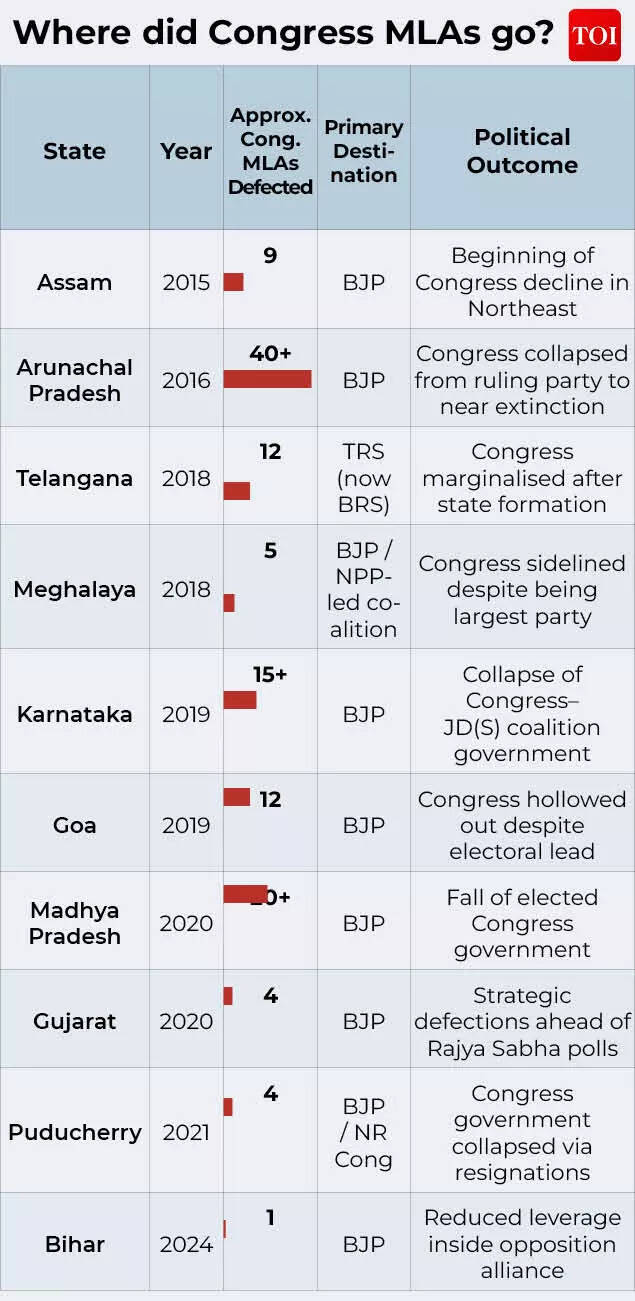

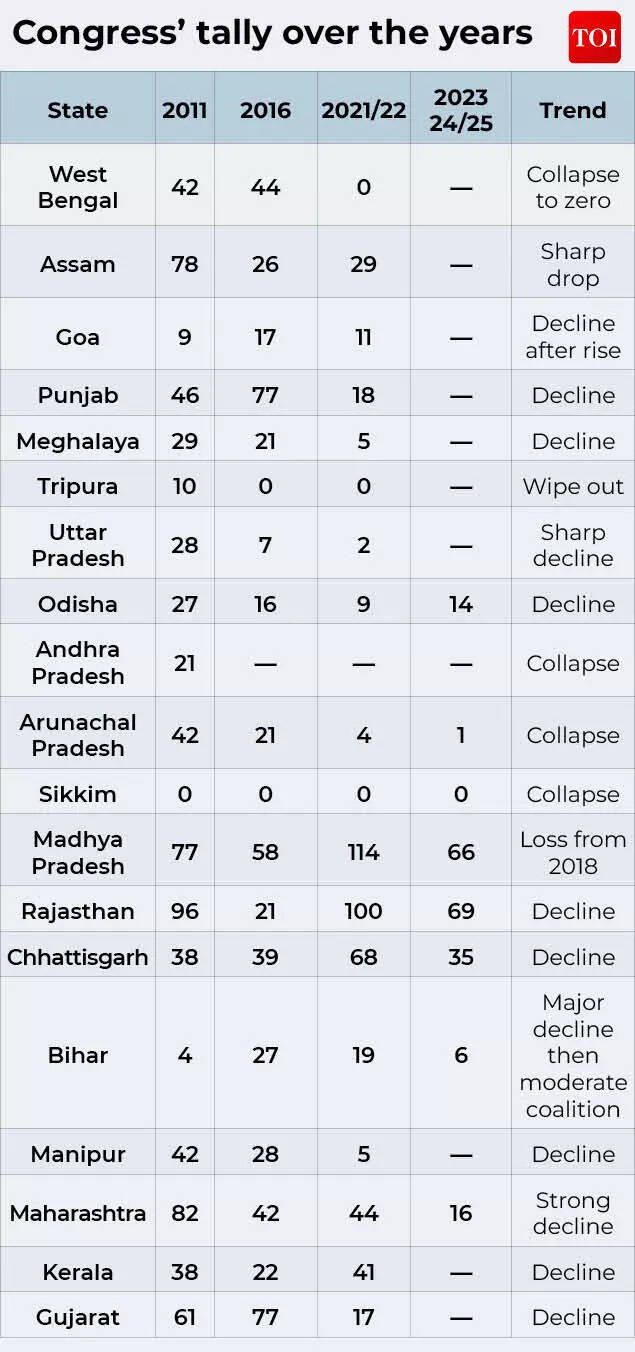

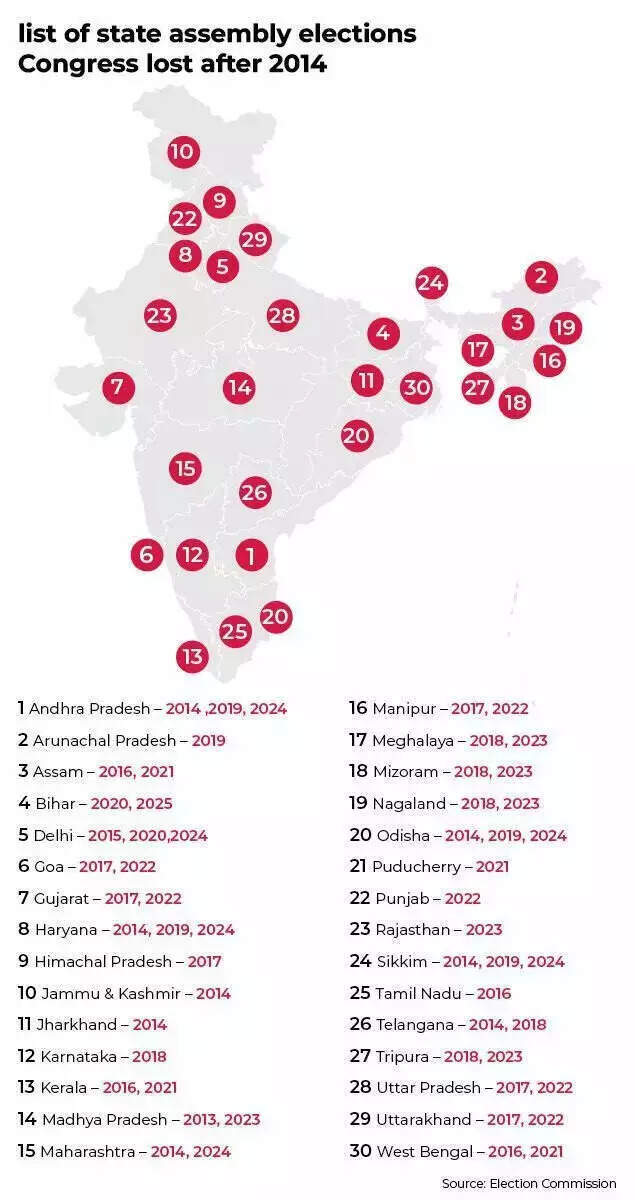

Mapping the exodus: When and where Congress lost its leadersPlacing defections on a timeline makes clear that this is not a sudden collapse but a decade-long, state-by-state unravelling. The exits accelerate after 2014, peak between 2017 and 2021, and continue in smaller but steady waves thereafter, often coinciding with leadership disputes, alliance breakdowns, or changes in government at the Centre.

Seen together, these timelines show how defections often follow a familiar rhythm: electoral setback, leadership dispute, prolonged indecision by the high command, and finally, coordinated exits. In several cases, these exits did not merely weaken the Congress but altered governments without voters being consulted again, underscoring how power has increasingly migrated away from the ballot box.Ambernath: A small town, a big signalOn paper, Ambernath is just another municipal council in Maharasthra. In practice, it became a live demonstration of how numbers trump ideology.The election produced a fractured mandate. The Shinde-led Shiv Sena emerged as the single largest party but fell short of a majority.

The BJP, Congress, and NCP—otherwise rivals—came together post-poll to form a bloc, the Ambernath Vikas Aghadi, not out of shared values but shared arithmetic. The sole aim was to keep Shiv Sena out of decision-making.This uneasy arrangement exposed contradictions within all parties involved. For the Congress, aligning with the BJP at the local level clashed with its national narrative. For the BJP, partnering with Congress councillors while attacking the party elsewhere created ideological discomfort.The Congress leadership chose discipline over pragmatism and suspended its 12 councillors. But suspension today is often not a deterrent—it is a signal. Within hours, the councillors crossed over to the BJP, turning punishment into opportunity.What followed—BJP minister Ashish Shelar publicly questioning the induction, NCP councillors switching sides again, and Shiv Sena regaining leverage—showed how fluid power has become, even within a matter of days.From exception to systemThere was a time when defections were treated as political scandals. Today, they are procedural events.Across India, resignations and party switches no longer happen quietly or individually. They occur in batches, at strategic moments, and with clear political outcomes in mind. What was once dismissively described as “Aaya Ram, Gaya Ram” politics has evolved into organised, legally informed, number-driven realignment.But this did not happen overnight.The great exodus: When defection became routineDefections are not new to Indian politics. What is new is their scale, their predictability, and their directional bias. Over the past decade, the Indian National Congress has increasingly come to resemble a feeder organisation in India’s political ecosystem, steadily supplying leaders, legislators, and organisational capital to rival parties.From municipal councillors to chief ministers, exits from the Congress have become so frequent that they no longer trigger moral outrage. Instead, they prompt a more unsettling question: is the party witnessing episodic rebellion, or is it undergoing a deeper organisational unravelling?What distinguishes the Congress’s current phase is the erosion of internal authority, which has transformed individual ambition into collective exit strategies. The numbers behind declineA look at the Congress’s parliamentary trajectory offers crucial context. Between 1999 and 2009, the party remained a central pillar of national politics, winning between 114 and 206 Lok Sabha seats and forming governments twice. The collapse in 2014, when its tally fell to 44, marked not just an electoral defeat but a psychological rupture. Marginal recoveries in 2019 and 2024 did little to reverse the perception of decline, particularly as state-level losses and defections continued unabated.While the Congress has managed periodic parliamentary rebounds, its organisational depth in states has thinned dramatically, making it vulnerable to post-election destabilisation.

What data shows: ADR maps direction of defectionsIn an analysis of elections held between 2014 and 2021, Association for Democratic Reforms (ADR) found that the Bharatiya Janata Party emerged as the biggest beneficiary of defections, while the Congress suffered the maximum losses, bleeding candidates and legislators across states and election cycles. ADR examined the self-sworn affidavits of 1,133 candidates and 500 MPs and MLAs who switched parties and re-contested elections during this period, including by-elections. The findings were stark. As many as 222 Congress candidates—the highest among all parties—left the party to join other formations before contesting elections. By comparison, 153 candidates exited the BSP during the same period. At the legislative level, the picture was even more damaging for the Congress.

Nearly 35% of all MPs and MLAs who switched parties—177 out of 500—were from the Congress, while only 7% defected from the BJP. On the receiving end, the BJP absorbed 173 MPs and MLAs, or 35% of all defectors, cementing its position as the principal magnet for political migration. Overall, 22% of all re-contesting defectors joined the BJP, far ahead of the Congress and other parties. ADR’s analysis underscores that what is often portrayed as isolated rebellion is, in fact, a sustained structural pattern.

The organisation noted that the persistence of defections reflects deeper pathologies in Indian politics, including the absence of value-based politics, the nexus between money and muscle power, and weak internal regulation of political parties. From “Aaya Ram, Gaya Ram” to engineered migrationIndia’s political history has long been marked by dramatic defections, famously coined “Aaya Ram, Gaya Ram” in the late 1960s, after a Haryana legislator switched parties three times in a single day. Such episodes highlighted the fragility of coalition politics and the ease with which personal ambition could override party loyalty. In response, the Anti-Defection Law was enacted in 1985 to curb opportunistic switching. It penalised individual legislators who defected after being elected, with disqualification from their seat serving as a deterrent. For a time, the law worked: governments completed their terms, and reckless, impulsive defections slowed.

But politics adapted. As legislators and parties became more strategic, defections evolved into coordinated, legally compliant maneuvers. By resigning in groups or exploiting procedural loopholes, politicians could now shift allegiances without violating the letter of the law. What began as isolated acts of opportunism turned into a structured, numbers-driven process—one where legal safeguards prevented punishment but could not restore party cohesion or curb the erosion of organisational authority.As Indian politics professionalised and power centralised, defections did not disappear—they evolved. Resignations replaced rebellion. Legal loopholes replaced political shame. What emerged was a model of post-election government construction where numbers mattered more than mandates.The leadership disconnect In recent months, the Congress’s internal churn has burst into public view through letters and open dissent. Former Odisha MLA Mohammed Moquim’s letter to Sonia Gandhi, calling for “open-heart surgery” within the party, crystallised a sentiment long whispered within party ranks. Citing repeated electoral defeats in Odisha, Moquim flagged a growing disconnect between the leadership and grassroots workers and questioned whether the party’s leadership could still resonate with younger voters.His complaint that he had not been granted an audience with

Rahul Gandhi

for nearly three years struck a deeper chord.

He described the issue not as personal grievance but as an emotional rupture felt by workers who believe their voices no longer travel upward.

Similar concerns surfaced during the Bihar assembly elections, where seat distribution talks exposed the distance between the central leadership and state units, triggering protests by denied ticket aspirants and demands for leadership changes.These episodes point to a structural problem: grievances accumulate slowly within the organisation, while decisions descend abruptly, often without consultation or explanation.From a party of plenty to party of precarityThe Congress’s present predicament stands in stark contrast to its early history. Founded in 1885, it was once defined by abundance—of leaders, of ideological currents, of organisational depth. During the freedom struggle and the early decades after Independence, the party functioned as a broad national canopy under which internal disagreements were absorbed rather than fatal.That breadth became harder to manage as politics decentralised and competition intensified.

By the time the Congress approached the 2014 Lok Sabha elections, it was burdened by anti-incumbency, corruption allegations, and leadership fatigue.

The emergence of Narendra Modi and the BJP’s organisational consolidation delivered a blow from which the party has struggled to recover. Since then, the Congress has faced recurring infighting, disillusioned workers, and senior leaders exiting after flagging unresolved concerns.Leaders such as

Sanjay Nirupam

, expelled from the party, have alleged that competing lobbies operate around senior figures, creating paralysis rather than clarity.Prolonged leadership tussles in Karnataka, Rajasthan, and Madhya Pradesh illustrate this hesitation to act decisively, often at significant electoral cost. In Rajasthan, the decision to back Ashok Gehlot over Sachin Pilot resolved neither factional rivalry nor voter disillusionment, culminating in defeat.

Similar patterns have played out elsewhere, reinforcing perceptions of drift.Rahul Gandhi’s role has also been scrutinised. Despite high-profile campaigns and yatras, his interventions have not consistently translated into electoral success.

Electoral slide and alliance fatigueSince 2014, the Congress has lost more elections than it has won. Even when it shows signs of revival in parliamentary contests, the momentum often dissipates at the state level.

Maharashtra reduced it to the margins. Bihar halved its strength. Haryana dashed hopes of converting parliamentary gains into assembly success. Delhi continues to remain out of reach.

The few regions where the party has performed relatively better—such as Jammu and Kashmir, Jharkhand and Himachal Pradesh—are those where it contested as a junior partner. Yet alliances bring their own complications. Many regional parties aligned with the Congress were born out of splits from it or emerged in opposition to it, making coordination fraught. Tensions with the National Conference in Jammu and Kashmir and the turbulent relationship with the Aam Aadmi Party within the INDIA bloc have repeatedly surfaced in public, confusing cadres and weakening ground-level coherence.Defection as democratic stress testThe consequences of this churn extend beyond party fortunes. Municipal councils and state assemblies are not merely arenas of power; they are training grounds for democratic leadership. When defections become normalised at these levels, transactional politics becomes foundational rather than exceptional.For voters, the implications are corrosive. Governments change without elections. Mandates appear provisional. Over time, this breeds cynicism not just towards parties but towards representation itself. Democracy survives procedurally, but legitimacy erodes substantively.In politics, the question is no longer why leaders leave the Congress. It is who, and what, is left to hold it together. The Anti-Defection Law, intended to stabilise governance, has become a legal framework within which these exits are now engineered—highlighting that procedural rules cannot replace organisational strength or political cohesion.

2 hours ago

4

2 hours ago

4

English (US) ·

English (US) ·