ARTICLE AD BOX

A tourist takes a picture in an abandoned kindergarten in the ghost village of Kopachi near Chernobyl Nuclear power plant during their tour to the Chernobyl exclusion zone on April 23, 2018.Read Less | SERGEI SUPINSKY/AFP/Getty Images

Nearly forty years after the 1986 nuclear accident near Pripyat, scientists have found measurable genetic changes in people whose fathers were exposed to the fallout while living in the town or working at the reactor site.

The research links radiation exposure in the original generation to specific mutation patterns appearing in their children, a connection that earlier studies repeatedly failed to detect. Instead of searching broadly for any mutation, the team focused on a particular fingerprint of radiation damage, revealing a transgenerational trace that persisted long after the explosion and evacuation that turned the region into the exclusion zone still in place today.

A different way of searching finally revealed the link

For years scientists asked a straightforward question: did the radiation alter children’s genes? They usually looked for any new mutation appearing in a child but absent in the parents. In the case of Chernobyl, that approach repeatedly failed to show a clear connection.For decades researchers tried to determine whether radiation from Chornobyl altered the DNA of the next generation. Those efforts largely came up empty because they searched for individual mutations passed from parent to child.

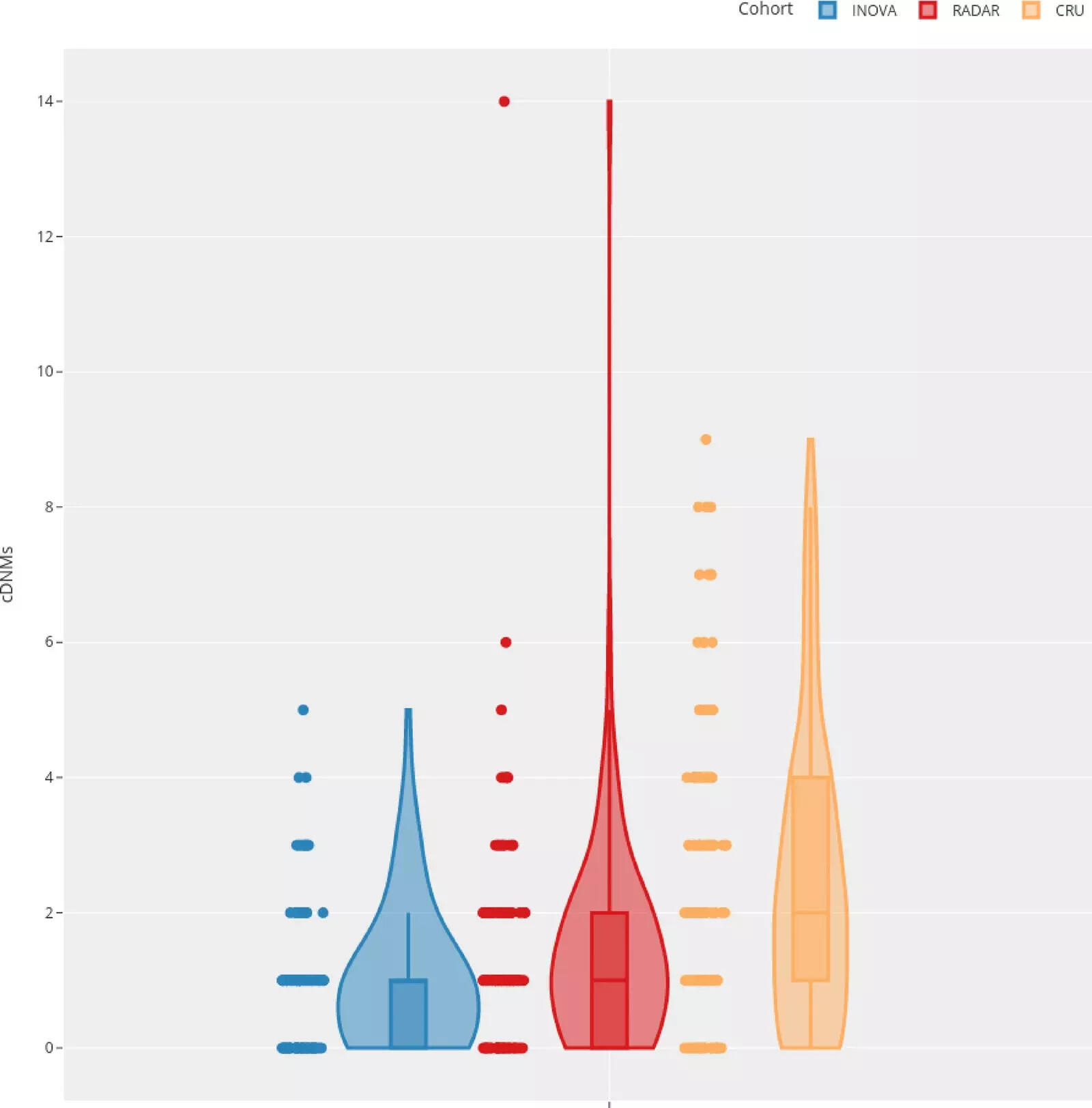

The new study approached the question differently by examining something called 'clustered de novo mutations' (cDNMs), which are small groups of mutations appearing close together in a child’s DNA but not present in either parent. To test this, the team sequenced the genomes of three groups:

- 130 children of Chernobyl cleanup workers and residents

- 110 children of German military radar operators exposed to stray radiation

- 1,275 people whose parents had no radiation exposure

On average, children of cleanup workers had 2.65 clusters each, radar-operator children had 1.48, and the unexposed group had 0.88.

Even after accounting for statistical noise, the difference remained meaningful.

Researchers have shown that children of Chernobyl cleanup workers (orange) and German radar operators exposed to stray radiation (red) have a higher number of mutations in their genes than the average person (blue)

In their paper, published in the journal Scientific Reports, the researchers write: “We found a significant increase in the cDNM count in offspring of irradiated parents, and a potential association between the dose estimations and the number of cDNMs in the respective offspring,” describing it as evidence for “the existence of a transgenerational effect of prolonged paternal exposure to low-dose ionising radiation on the human genome.

” In simple terms, they finally detected a pattern of inherited damage, not random mutations, but a radiation-type signature.

How radiation in 1986 ended up in the next generation’s DNA

The parents included in the study had either lived in Pripyat during the accident or worked as “liquidators” guarding and cleaning the reactor site after the explosion on 26 April 1986, which displaced more than 160,000 residents. Ionising radiation creates unstable molecules called reactive oxygen species.

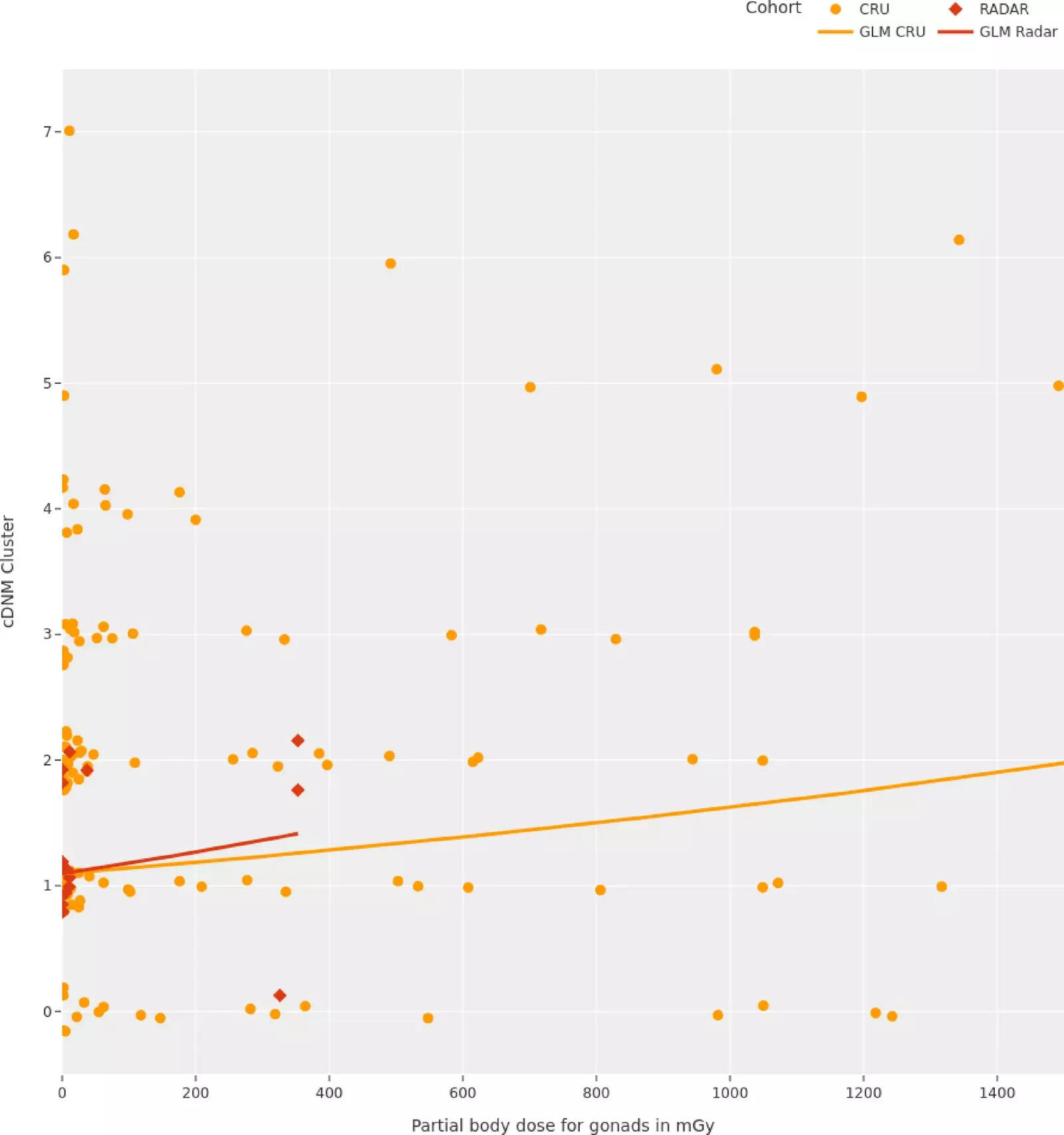

These molecules can break DNA strands inside developing sperm cells. When the body repairs those breaks, tiny groups of mutations can remain. Years later, those repaired strands become part of a child’s genome. The researchers also saw a dose relationship: higher parental exposure generally meant more mutation clusters in the child. Estimated exposure averaged about 365 milligrays, below levels associated with acute radiation sickness and lower than the 600-milligray career limit set for astronauts, but still enough to leave a detectable genetic trace.

The more radiation someone was exposed to, the more mutations their children had

Because exposure happened decades ago, the team relied partly on historical records and old measuring devices to estimate dose, and participation was voluntary, both factors the authors list as limitations. They add that “the potential of transmission of radiation-induced genetic alterations to the next generation is of particular concern for parents who may have been exposed to higher doses of IR and potentially for longer periods of time than considered safe.

”

What the mutations actually mean for health

The researchers examined where the mutations appeared in DNA. Most were located in non-coding regions, parts of the genome that do not produce proteins. That matters because harmful genetic diseases usually involve coding regions. Accordingly, they did not find a higher disease risk among the children studied. The paper explains: “Given the low overall increase in cDNMs following paternal exposure to ionizing radiation and the low proportion of the genome that is protein coding, the likelihood that a disease occurring in the offspring of exposed parents is triggered by a cDNM is minimal.” For perspective, the scientists also note that a father’s age at conception contributes more to disease risk than the radiation exposure measured here. The result is a specific kind of finding: the disaster left an inherited biological signature, visible in DNA decades later, but not one that translated into measurable illness in the group studied.

1 hour ago

6

1 hour ago

6

English (US) ·

English (US) ·